Jazz Retrospective: The Indelible Impact of “Emergency!” by the Tony Williams Lifetime

By Steve Elman

Their first release was complete in itself, taking many of the ideas of free jazz and grafting them onto a rock foundation at a deafening volume. We can now see that expecting a second act from this singular moment of Tony Williams’s work was too much to ask. But that hasn’t stopped generations after from returning to it for inspiration.

Their first release was complete in itself, taking many of the ideas of free jazz and grafting them onto a rock foundation at a deafening volume. We can now see that expecting a second act from this singular moment of Tony Williams’s work was too much to ask. But that hasn’t stopped generations after from returning to it for inspiration.

You never forget your first time.

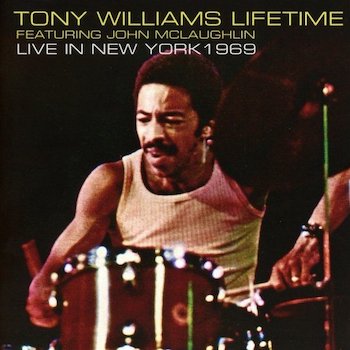

The first time some of us heard drummer Tony Williams and the original Lifetime, his short-lived power trio with guitarist John McLaughlin and organist Khalid Yasin (aka Larry Young) was one of those indelible times.

For those who came to love that band, the first moment of their first LP set Emergency! had the same impact as the first fiery morsel of real Kung Pao Chicken. It was like our first plunge into 50-degree water. It was like the first time we saw blue lights in our rear-view mirror and realized a police officer wanted us to pull over. Our brains went blank for a second trying to process what the senses were delivering.

Then the neurons began trying to understand this music we were hearing. Was this the impeccably sensitive drummer who had been such an elemental force in Miles Davis’s band? Was this the rock-inflected guitarist who had punched up some of Miles’s best electric sessions? Was this the visionary organist who had been changing the very idea of the Hammond B-3 on his innovative Blue Note releases?

Could this dense, intense music really be the work of just three players?

And then we had to play those four LP sides again . . . louder.

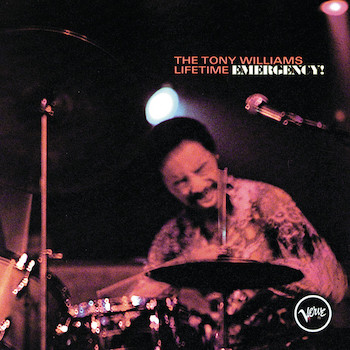

Almost everyone complained about the mix and the pressing of the original 1969 Polydor LPs of Emergency!. You felt that there was so much going on, at such a high level, that you wanted to hear every detail — and anything that got in the way was frustrating. There was a reissue (Once in a Lifetime, Verve, 1982) with much improved sound, produced by James Isaacs (who also wrote the liner notes, with some of the best words written up to that time about the group). More work on the session came in 1991, when Richard Seidel oversaw new production and Phil Schaap did the remix that is the basis for the CD versions that are now in circulation.

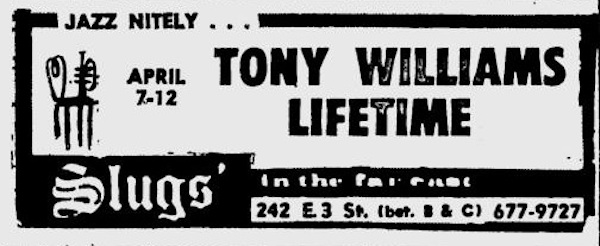

Maybe you were among the lucky few who got the opportunity to hear the original Lifetime live. I made a pilgrimage to NYC in January 1970 to experience the band at the now-legendary dive called Slugs’ (they put that apostrophe into their ads, so I’m honoring the usage here). After the first set, with my ears ringing, I came out of the club astonished to find that the band hadn’t melted the snow off the sidewalk.

Williams kept that trio going for just a year or so, and then added Jack Bruce on bass and vocals, which moved the music into less abstract and more rock-oriented territory. This version of the band recorded a second Lifetime record, Turn it Over (Polydor, 1970). Its impact wasn’t quite the same as that of Emergency!, but one track, “Vuelta Abajo,” had something close to the intensity veteran Lifetime fans expected.

Soon after, McLaughlin was gone and Ted Dunbar came in on guitar for a more diffuse third album, Ego (Polydor 1971), which Stewart Matson of allmusic.com calls “easily the weirdest record the Tony Williams Lifetime ever released.” Still, it featured the debut of “There Comes a Time,” Williams’s most accomplished tune with lyrics.

The fourth Lifetime LP, The Old Bum’s Rush (Polydor, 1973), was better, but almost as diffuse as Ego, this time without a star guitarist. The new members of the band, keyboard players Webster Lewis and David Horowitz and new vocalist Laura “Tequila” Logan, were given few opportunities to shine.

After those three LPs, Williams reinvented the idea again, in a band that has been called Wildlife, but was really the last edition of Lifetime, bringing back Bruce on bass, keeping Lewis and Logan, and adding new guitarist Allan Holdsworth, a speed king to rival McLaughlin. This group recorded a session in Stockholm that seemed like a cohesive step forward, adding funk elements to the original power-trio concept and integrating Logan’s vocals more effectively than before, but that recording (available as a bootleg and hearable via Youtube) fell between recording contracts and never saw official release.

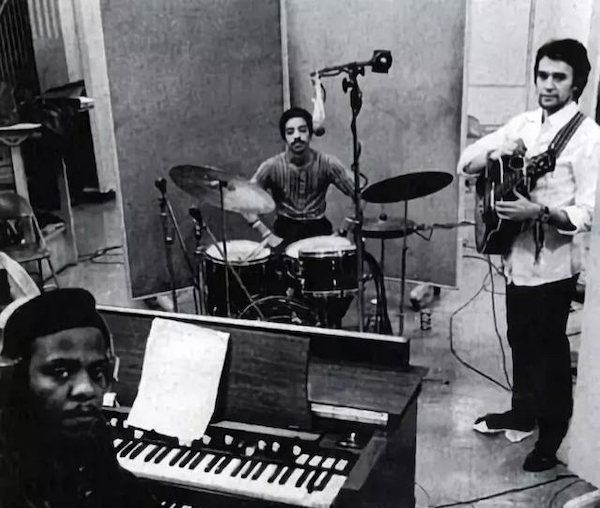

The original Tony Williams Lifetime – guitarist John McLaughlin, drummer Williams, and organist Larry Young (later Khalid Yasin).

Then Williams seemed to realize that the lightning had truly left the bottle, and he moved on, as he had done all his life, to the new and different, occasionally looking back, but usually trying for a different stroke. Keyboardist Alan Pasqua (fondly remembered by many Bostonians) passed through the ranks of Williams’s groups, though Pasqua was never given the chance to show the full depth of his talent on Williams’s CDs.

In 1979, the ghost of Lifetime rose again for a few months in Trio of Doom, which reunited McLaughlin and Williams, with Jaco Pastorius playing bass. And in 1980, Williams revisited the power trio concept one more time with bassist Patrick O’Hearn and keyboardist Tom Grant. This group’s only recording, Play or Die, has just re-appeared (companion review post).

And then it really was done, for good and all. Williams went back to post-bop for his last three releases (which contain some of the late Wallace Roney’s most inspired trumpet work and beautiful piano playing by Mulgrew Miller), although his drumming on those showed more force and a stronger bass drum than he had used in his previous work in that style.

It wasn’t that the music after Emergency! was anticlimactic. That first release was simply complete in itself — taking many of the ideas of free jazz and grafting them onto a rock foundation at a deafening volume, and we can now see that expecting a second act was too much to ask.

What made this band such a special combination? Part of its framework was the inspiration of Miles Davis, who was just beginning to move decisively into his fusion phase when Emergency! was recorded in May 1969. Three months before, in February, Williams and McLaughlin had worked together in the sessions that eventually produced In a Silent Way, but that music was contemplative in comparison to the fury unleashed in Lifetime. Still, Williams knew that Miles had his finger in the air and sensed a shifting wind.

To a very real degree, when Larry Young (later Khalid Yasin) joined Williams and McLaughlin to create Lifetime, they caught the wind in full sail, and sped ahead of Miles, who would not make electric music so abstract or committed until 1972.

To a very real degree, when Larry Young (later Khalid Yasin) joined Williams and McLaughlin to create Lifetime, they caught the wind in full sail, and sped ahead of Miles, who would not make electric music so abstract or committed until 1972.

Williams’s physical gifts as a drummer were always prodigious, but he had never before used them at the volume level employed in the Emergency! sessions. He had the raw power of many great (and not-so-great) drummers. However, Williams’s power was driven by a supremely musical intelligence and a conception of the drums as a single musical instrument, an approach that’s still all too rare, one pioneered and perfected by Max Roach and brought to a new level by Williams.

McLaughlin’s skill and speed as a guitarist weren’t the most important things he contributed to Lifetime. His sense of complex harmony and his addition of jarring notes at the tops of his chords were integral to making this driving music thick with harmony and intellectually challenging at the same time it was viscerally thrilling. He also responded to the lack of a bassist by occasionally interjecting pungent bottom notes to add more kick.

Larry Young / Khalid Yasin is always The Other Guy in the band. It’s about time his distinctive contributions were appreciated fully. He is credited with bringing a completely distinctive voice on organ into the trio, but his sonic daring — using dramatic shifts in dynamics, unusual stops, spacey sounds, Sun Ra-like chords, sudden waves of vibrato from his Leslie cabinet, and a bit of distortion produced by straining his amp, were only parts of the story. He was also a particularly adept bassist, playing organ notes with his feet that did far more than provide a bottom; his ability to move the bass lines as nimbly as the spontaneous flow of the music demanded gave Lifetime a remarkably flexible foundation.

In addition, it was Young who had made the recordings that most prefigure Emergency!. For a fine example, listen to “Major Affair” from Young’s Contrasts (Blue Note, 1967). The entire track is a duet with drummer Eddie Gladden, which sounds (if you turn it up) like his interactions with Williams two years later.

Rarely have such original thinkers combined their abilities in such a cohesive way, making music that sounded like it had emerged fully formed from nowhere — like nothing most of its listeners had ever heard before.

And the studio sessions were not a fluke. Anyone who heard the band at Slugs’ will tell you that the intensity of the LPs was fully on display in live performance, and there are even bootlegs circulating that prove it. Those unauthorized recordings contain at least one tune (untitled as far as I know) that was not on the LPs. Someday, with a little luck and some computer wizardry, maybe even that bootleg stuff will be made listenable.

Those who loved Emergency! at first sound were changed by the experience of hearing it. After hearing it, we non-musician listeners knew that the most adventurous music could exist viscerally, in a way that could move the body as deeply as it moved the mind and the soul. It opened a door in the mind.

Inevitably, some of the young players who heard Emergency! eventually wanted to try their hand at something similar, either in tribute to it or in an attempt to see what could be done with similar tools.

The various revivals of the original Lifetime concept each have their merits. But before I review them, it may be useful to insert a side note about Carla Bley’s composition “Vashkar,” which, as a result of its recording on Emergency! and in the revivals, gained currency with many more listeners than it had ever had before. Along the way, it may have earned more in residuals for the composer than any other single composition of hers.

The tune started life in 1963, when Paul Bley recorded it (along with three other Carla Bley compositions) on his trio album Footloose (Savoy, 1963), before Carla Bley had formed her own band or begun performing as a pianist. Its memorable five-note central motif has an Indian flavor, and Carla Bley probably intended it so, since the title is a fairly common first name in India. Paul Bley’s original interpretation moves quickly from the theme into free improv in a cerebral post-Bill Evans trio vein.

Carla Bley made that motif a prominent feature of “Rawalpindi Blues,” which debuted in her “chronotransduction” Escalator Over the Hill (JCOA, 1971), where it was given lyrics by Paul Haines and sung by Jack Bruce.

In recent years, the composer has reclaimed the original tune, recording a version for Trios (ECM, 2013) that wittily quotes Ravel’s “Bolero” and adopts something of Ravel’s rhythm.

But Bley’s tune was transformed when Tony Williams and Lifetime chose “Vashkar” for Emergency! in 1969. They sped it up and invested it with red-blooded thrash, deemphasizing the five-note motif in favor of a stream of unison notes from organ and guitar, underpinned by Williams at his most roiling, followed by guitar and organ solos that ignore the changes and slide into free improv. It’s one of the most economical tracks on Emergency! and one of the most immediately effective.

The first effort to revive Williams’s 1969 idea was Trio of Doom in March 1979, with John McLaughlin and Jaco Pastorius. This was more of a producer’s concept than a real band, assembled as a one-off supergroup for the Havana Jazz Festival. It covered none of the original Lifetime material. McLaughlin responded well to Williams, as he had always done, but the tension between Pastorious and the drummer (both formidable egos) meant that the combination couldn’t last long enough to find a real voice. The recordings show plenty of power but little discipline. Its five-tune repertoire first appeared on Havana Jam (CBS, 1979), but it took almost thirty years for a “complete recordings” CD to appear, in Trio of Doom (Columbia Legacy, 2007), which added studio takes of the same material.

In November 2004, the original Lifetime got its first serious re-appraisal, when drummer Jack DeJohnette brought guitarist John Scofield and organist Larry Goldings together in what became known as Trio Beyond. Their one recording, Saudades (ECM, 2006), in front of a live audience at the London Jazz Festival, covers “Allah Be Praised” (by Larry Young / Khalid Yasin, originally heard on Turn It Over), and three of the classics from Emergency! – “Spectrum” (by John McLaughlin), “Big Nick” (by John Coltrane) and “Emergency” (by Williams), plus the surprise addition of a tune Williams wrote for Miles Davis’s Nefertiti, “Pee Wee.” These three hugely original players pay their respects to Williams without imitating Lifetime, and most of the music is very satisfying.

Scofield had filled John McLaughlin’s shoes before — as he did when he played with Miles — but he is not the same kind of guitarist, and he didn’t try to be for Trio Beyond. McLaughlin always seems to be pushing forward in his playing, investing the staccatos with a lot of dramatic tension. Scofield’s work is almost always centered, rooted, and often behind the beat, even at fast tempos. This quality gives Trio Beyond a less frenetic quality than that of the original Lifetime.

Goldings never tries to imitate Young’s other-worldly effects; instead, he often introduces vocal samples, which change the complexion of the music in distinctive ways. And DeJohnette is gracious (and mighty) in interpreting another master drummer’s work without ever emulating it.

The most substantial body of work honoring the original Lifetime comes as a result of the devotion of one of Tony Williams’s most passionate acolytes – Cindy Blackman Santana. She has modeled her drumming on Williams’s much as Steve Lacy modeled his composing on Thelonious Monk’s. For four years, from 2007 through 2011, Blackman Santana returned again and again to Lifetime, and championed its music in her work with others. And she has been a particular fan of “Vashkar.”

She first recorded Lifetime material in an October 2005 session, where she sang and played on “There Comes a Time” (originally from Ego, and re-recorded in 1980 by Williams in Play or Die, which has just been reissued). She chose to duplicate the no-bass-guitar approach of the original band then, with Carlton Holmes providing keyboard bass and chording, and Fionn O’Lochlainn slashing away on guitar. This doesn’t really shade the 1980 Williams version she chooses as a model, because her vocal isn’t as committed as Williams’s. However, in copying the idea of a closing drum solo over a stop-time vamp, she does her mentor proud, and even introduces a dramatic rest that sets up her final flurry with admirable tension.

She came back to Lifetime in a March 2007 session with guitarist Mike Stern, keyboardist Doug Carn, and bassist Benny Rietveld. They covered “Vashkar” (in three different arrangements), “Beyond Games,” and “Where,” all from the Emergency! sessions. “Beyond Games” is maybe the best of the three covers, given a somewhat lighter touch than the original Lifetime’s, but funkier, too, thanks to Rietveld’s very substantial bass playing and a more gospelly feel in Carn’s organ work. Stern, of course, knows this territory well, and he has all the guitar passion needed.

Both of those sessions eventually were included in Blackman‘s first solo CD, Another Lifetime (4Q, 2010).

In 2008, she joined Spectrum Road, which wasn’t even known by that name in its first sessions. Bassist Jack Bruce, like Blackman a devoted Williams fan, returned to material he obviously loved, and the band was completed by guitarist Vernon Reid and keyboardist John Medeski. Some December 2008 live performances in Japan have come to light on Tony Be Praised (Invisible Works, 2009). The recording is amateurish (with vocals way off-mic), but three sets are captured, including three takes of “Vuelta Abajo” (originally on Turn It Over), three of “There Comes a Time,” three of “Where,” two of “Beyond Games” (originally on Emergency! ), two of “Emergency”, and one each of “Allah Be Praised” and “One Word” (both from Turn It Over) and “Wildlife” (originally on Believe It, from 1975). Reid is very strong throughout the sets, and the performances of “Vuelta Abajo” here are already committed and forceful. However, most of the other tunes seem like they need more work, and Medeski is a bit in the shadow of the other three players throughout the performances.

A little more than two years later, Spectrum Road went into the studio for what has become the most comprehensive revisit to date of the repertoire of the original Lifetime and its successor bands. Because it covers a lot of territory, the repertoire isn’t sharply focused, but the covers of the original Lifetime tunes are admirable. Medeski finds his proper place at last, making contributions in his own voice that are as interesting in their way as Young’s were in the first edition of the band, and even adding mellotron to some of the tracks. Blackman (now with the additional surname of Santana thanks to her new husband Carlos) channels Williams effectively on all the tunes, and kicks things harder on some.

They returned to a lot of the material they’d played on the road – “Vuelta Abajo,” “There Comes a Time,” “Where,” “Allah Be Praised,” and “One Word.” They added ”Vashkar,” and a later Williams tune, “Coming Back Home” (from The Joy of Flying [Columbia, 1978]), along with some new material.

Weirdly, the mix on the CD is almost as thick as that on the original Lifetime sessions, which probably was an artistic choice – but neither Reid’s guitar nor Bruce’s bass are as cleanly recorded as this listener would like; they sound like their amps have been baffled in cardboard boxes.

“Vashkar” is a standout track, with lots of impact. Reid and Blackman Santana are just where they need to be, but the crucial changes come from the contributions of Medeski and Bruce. Medeski gets his teeth into the tune in his solo in a way that is very different from the way Young handled it, and Bruce steps up with surprising ingenuity. The original track had no bassist, so Bruce has free rein to go his own way here; instead of the modal foundation that he used to underpin Cream’s jams, he is all over his axe throughout the track, adding a welcome bottom layer. The only thing wrong is the indeterminate ending.

The original Tony Williams Lifetime in action: John McLaughlin, drummer Williams, and organist Larry Young (later Khalid Yasin).

“Allah Be Praised” is almost as strong, with Blackman Santana kicking the backbeat even harder than Williams did on the original, and everyone playing at top form.

But even this session wasn’t Blackman Santana’s last stab at Lifetime. In July 2011, she joined Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin in a two-guitar summit session recorded live at Montreux, with superior support from bassist Benny Rietveld and David K. Matthews on keyboards. Santana sat out the Lifetime covers, leaving center stage to McLaughlin for “Vuelta Abajo” and “Vashkar” (once again). McLaughin is ferocious on both of them, taking real pleasure in revisiting tunes he first recorded more than four decades earlier, and even adding a Miles Davis lick as a vamp under Matthews’s solo in “Vashkar.” Rietveld is a much more adept bass player than Bruce was, and he shines on “Vashkar.” Matthews is not Larry Young, but he holds up his end with much more than lip service, and he is in top form on Carla Bley’s tune.

Not all of the material performed in the concert is at this level, but these two tracks alone almost make the set worth buying, and the cover of Miles’s “Black Satin” is an additional treat (Invitation to Illumination Live at Montreux 2011 [Eagle, 2015]).

People love Lifetime, as these revivals clearly show. If you don’t know those 1969 originals, get them and listen to them; you may fall in love too. And if you know the recordings well, listen to them again. No matter how familiar this 50-year-old music is to you, you’ll be struck by its timelessness. It is as if Williams, Young and McLaughiin – all now recognized as geniuses and primal forces on their instruments – are still playing at Slugs’, just down the block and around the corner.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Carla Bley, Cindy Blackman Santana, Emergency!, John McLaughlin, Khalid Yasin, Larry Young, Slugs', Spectrum Road, Steve Elman, Tony Williams, Tony Williams Lifetime

What are your thoughts on Tony’s appearance on Public Image Ltd’s. punk album, “Album”? Was it an all-star fluke (a project of Bill Laswell’s), or was it in line with other hardcore fusion sessions you discuss here? It was recorded in 1985, right in the middle of Williams’ return to acoustic post-bop jazz.

Great piece! Plus, you did Tony the honor of not mentioning his singing. 😉

Very interesting to find out that Tony Williams worked with PIL. I have an ambivalent response to Johnny rotten’s music to say the least but I’m intrigued by this.

I dream of a band that can combine garage rock with jazz. Imagine like early Rolling Stones or Psychotic Reaction by the count five but those crackling three chords are stretching out as an extended rhythm section while, say, Sonny Rollins or Coltrane plays a solo.

Are there any bands like that you or anyone who is listening might know of?

I can’t think of anything that corresponds to your idea, but may have just inspired someone at Berklee.

TRY THE THING TRIO

In the companion piece, I nod to Tony’s vocal efforts. By the time he recorded Play or Die, he actually achieved pretty good pitch control.

I was completely unaware of Tony’s collaboration with PIL, so thanks for that!. Laswell, of course, is a great synthesizer, and it may very well have been his idea.

You will never read a more accurate assessment of the Lifetime zeitgeist than Elman’s piece. He places the importance of “Emergency” and Tony’s subsequent efforts in the proper context with an analysis that is both factual and admiring. Some of us don’t want that awful “sounding” “Emergency” record to ever be fixed. Thanks to Steve Elman for sharing his expert take …

Many thanks for those kind words. Isn’t it amazing that this music inspires such passion after such a long time?

No mention of the New Tony Williams Lifetime and the two albums ‘Believe It ‘ and Million Dollar Legs ? I’m not a fan of the latter but Believe It with Holdsworth is a must, some major tunes like Fred and Snake Oil. Surely worth a mention ?

I think the New Lifetime really operated with a new conception, and thus fell outside the scope of this piece, which looks at the first edition’s direct impact. Your mention of Fred and Snake Oil just goes to show that Williams made more solid music in the years after the first Lifetime.

I did nod to Allan Holdsworth a bit in talking about Wildlife. So much great talent passed through Tony’s bands.

The trio of doom cd added the live tracks from Cuba not studio tracks! The original release were studio tracks recorded because Mcclaighlin didn’t allow the original live tracks to be released.