Opera Album Review: From Fascist Italy — With Love?

By Ralph P. Locke

An opera from Fascist Italy, Gino Marinuzzi’s memorable Palla de’ Mozzi receives a splendid world-premiere recording. Should you listen despite its pedigree?

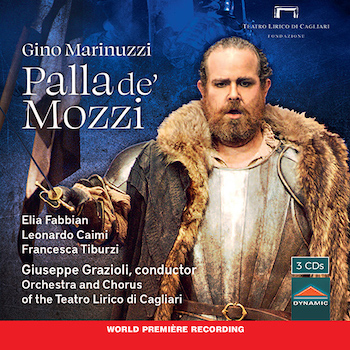

Gino Marinuzzi: Palla de’ Mozzi (opera)

Francesca Tiburzi (Anna Bianca), Leonardo Caimi (Signorello), Elia Fabbian (Palla de’ Mozzi)

Cagliari Teatro Lirico/ Giuseppe Grazioli

Dynamic 7925 [3 CDs] 138 minutes

Click here to purchase or to hear the beginning of each track.

How do we (should we, can we) respond to a work that was composed and hailed during a barbaric era in the history of the country that gave birth to it? This question has rarely been raised in regard to Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy: most of the composers that we admire today from those countries fled to other lands in order to escape persecution themselves, avoid complicity with a tyrannical government, or simply ensure themselves greater tranquility. (For lack of space here, I will skip over the prominent composers who chose not to leave Germany and Nazi-controlled Austria, including Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, and Karl Amadeus Hartmann. Each case is different and has been examined with some care by scholars and other commentators.)

How do we (should we, can we) respond to a work that was composed and hailed during a barbaric era in the history of the country that gave birth to it? This question has rarely been raised in regard to Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy: most of the composers that we admire today from those countries fled to other lands in order to escape persecution themselves, avoid complicity with a tyrannical government, or simply ensure themselves greater tranquility. (For lack of space here, I will skip over the prominent composers who chose not to leave Germany and Nazi-controlled Austria, including Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, and Karl Amadeus Hartmann. Each case is different and has been examined with some care by scholars and other commentators.)

But is it possible that we are missing out on some very imaginative and effective works? Also, aren’t we avoiding an important if unresolvable issue, namely how to balance (or integrate) aesthetic judgment, on the one hand, and political/ideological criteria, on the other?

The world-premiere recording (and it is fortunately a good one!) of an Italian opera from 1931 — when Mussolini’s fascism was already in firm control of Italian political and public life — provides an opportunity to think these matters through. I will start by focusing on “the work itself” (as music scholars and critics often say) and will return to the question of its original context later on.

Gino Marinuzzi is a composer whose career overlapped with that of Puccini and continued for some years thereafter. A rough equivalent, though in the area of comic opera, might be Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, composer of the oft-recorded I quatro rusteghi (1906; see my review).

Actually, there were two notable Italian musicians named Gino Marinuzzi, a father and a son. The father (1882-1945) — the composer we’re dealing with here — was well known, and greatly respected, as a conductor in Palermo (the capital of Sicily) and elsewhere. He introduced major Wagner operas to audiences at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, brought Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten to Italy, and was entrusted with the world premiere of Puccini’s La rondine (Monte Carlo, 1917; the tenor was no less than Tito Schipa).

In the midst of his busy conducting life, Marinuzzi Sr. also composed actively for orchestra and for the opera house. Marinuzzi Jr. (1920-1996) composed as well, becoming a prominent figure in the Italian electronic-music scene in the 1950s and 60s. Oxford Music Online has an entry for each of them and, somewhat perversely, a work list for the son but none for the father. It’s the father’s works that are most likely to hold the attention of posterity. Wikipedia lists the more important ones. The few recordings of his works to have been made available on this side of the Atlantic include his opera Jacquerie and some pieces for piano and for orchestra.

Marinuzzi is known to opera lovers today mainly as conductor of an oft-reissued 1941 recording of Verdi’s La forza del destino starring Maria Caniglia (“unmissable” according to Gramophone magazine’s 2010 guide). Palla de’ Mozzi (La Scala, 1932) was apparently his most successful opera: it was widely performed during his lifetime in Italy and beyond (Berlin, Buenos Aires). The plot takes place in the mid-16th century. Palla de’ Mozzi (apparently an invented character) is the commander of a band of mercenary soldiers (a mixture of Italians and “Landsknechte” from north of the Alps) fighting the forces of Spain and of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who were besieging Siena in order to end the republic there (as they would indeed succeed in doing in 1555).

The plot takes place sometime after the 1526 death of a Medici prince, Giovanni, who (this part is historically accurate) fought with the approval of Pope Leo X. After Leo died (1521), Giovanni put a black band on his insignia as a sign of mourning, and the mercenaries fighting with him thenceforth became known as the “Bande Nere”—the Black Bands.

The opera begins with Palla de’ Mozzi’s forces securing the region around Siena for the embattled republic. He has been excommunicated by the current pope (who sides with Spain and Charles V). In the first act, the commander’s “handsome son” Signorello enters the chapel of the castle of Montelabro (or Monte Labbro) and weeps at the atrocities of war that he has been forced to commit. (I henceforth omit quotation marks for phrases from the booklet’s plot summary.) Palla barges in and commands the bishop to bless the troop’s banners. When the bishop refuses and denounces him (in line with the pope’s anathema), Palla pushes him violently to the ground and blesses the flags himself.

In Act 2, set in the castle, Lord Montelabro and his daughter Anna Bianca try to hide from the mercenaries. Palla seizes the young woman and offers her to his four valiant captains, who throw dice to determine which of them may have his way with her first. But she uses her wiles, bribing them into sparing her father and letting her meet with Signorello. They leave. Signorello has overheard all and decides to set her free, though he will be put to death for it. The two, recognizing each other’s bravery, sing of their near-instantaneous love bond.

In Act 3, Palla returns, ready to send Anna-Bianca’s father to the scaffold. He is told that Signorello (his son, remember) has allowed the lord of the castle to escape, and, feeling his family honor betrayed, runs himself through with his sword. Signorello declares that Giovanni of the Black Bands never intended to pit Italians against each other. Palla recognizes his offspring’s noble heroism and gives him his sword to continue the fight for Italian national unity.

There is much violence, or threat of violence, throughout the opera, but the final minutes focus on noble sentiments, what with Palla’s literal self-sacrifice followed by a fine stentorian solo for Signorello and a powerful choral hymn, both of them hailing Italian patriotism, the great cause that had animated so many Italians in the 19th century (including Verdi) until Italy finally became a unified nation in the 1860s.

How the intense turns in the plot might relate to the disturbing events of Marinuzzi’s own era is a matter left unmentioned in the booklet. Mussolini was already, in the 1920s and early 30s, seeking to build a colonial empire in Libya and bombing Corfu. Within a few years, he would attempt to conquer Ethiopia and would side with Franco in Spain (and, of course, eventually with Nazi Germany and Japan). Perhaps wisely, the librettist (Giuseppe Forzano) kept the emphasis on such classic themes as romantic love, quick-wittedness (Anna Bianca), merciful action (Signorello’s complicity in Montelabro’s escape), and national self-determination (the republic of Siena as a foretaste of Italian unification).

In addition, Forzano made use of a well-tested operatic device in putting a relatively isolated female character at risk from the machinations and urges of powerful men. We find instances in such otherwise disparate operas as Il Trovatore, Tosca, and Pelléas et Mélisande. A nice touch: the librettist mutes the possibility of sexual violence by having Anna Bianca take charge of the scene with the four captains. Her bribing them with 40,000 scudi to split four ways effectively undercuts Palla’s military leadership. It also generates sympathy for these mercenary warriors, as each sings tenderly about his homeland, much as do the Chinese ministers Ping, Pang, and Pong in Puccini’s Turandot.

Does all of this suggest that Forzano and, in his footsteps, Marinuzzi were taking care not to comment in any way on current doctrines and military ventures? And, if so, was this cowardly on their part? Or did a refusal to echo Fascist doctrines and obsessions itself amount to an admirable (if subtle) resistance effort?

Composer Gino Marinuzzi

None of this would matter much if the music weren’t fresh, involving, memorable, and appropriate to the events as they unfurl. I approached the work with skepticism, then found myself won over time and time again by the clarity of musicodramatic utterance and the sureness of the composer’s hand. Musical numbers never outstay their welcome — there are big choral moments (for nuns, choirboys, soldiers, etc.) that are all effectively contrasted with each other and with the music for the main characters. Many arias and duets are beautifully structured and would transfer well to a voice recital, a vocal concert with orchestra, or an album of excerpts from forgotten operas. I am particularly fond of Signorello’s agonized aria of remorse in Act 1, sung after some interchanges with two nuns who have repeatedly noticed him praying there. (The events of the opera take place on Easter weekend. This gives added richness to the church scenes.)

The musical style is hard to describe: tonal throughout, but with numerous touches of what was considered “advanced” harmony in the early 20th century, such as parallel chords in the Debussyan manner. (One recurring motive alternates between two major triads a whole-tone apart.) Much of the time, I felt that I could as well be listening to a work from the 1870s-90s by, say, Lalo or d’Indy, to mention two composers whose styles were quite different from each other, just as the styles in this work vary from scene to scene. There’s nothing wrong with a work hewing to the traditional. Not every composer has adhered to current fashions about what was considered “progressive.” (Think of Bach or Brahms in the context of their respective contemporaries.)

In addition, the vocal lines are shapely, allowing a singer to soar, and the orchestration is considerate, often scaling back during vocal passages and then surging and glittering during act-preludes and in the instrumental coda to a musical number. In those fuller moments, I was sometimes reminded of the sunnier sides of Mahler (Symphony No. 4, fourth movement) or Strauss (Der Rosenkavalier).

The recording was made during a staged production in Cagliari (the capital of Sardinia). You can get a sense for the staging from a YouTube trailer for the CD. YouTube also has some interesting scenes shot during rehearsal, with a mock-up of the set — big empty blue panels — and different singers in the roles of Anna Bianca and Signorello.

Everybody in the CD recording sounds involved yet vocalizes securely. There is a certain amount of slow (but fortunately narrow) vibrato on long notes and slightly underpitch singing. But, as is often the case with big voices, tone production solidifies as the opera goes along. Furthermore, there’s a vitality here that might have been hard to achieve in a studio recording. The orchestra plays beautifully, reminding me once again how standards of instrumental playing have risen everywhere in the past half-century. The chorus is always in perfect agreement with the orchestra (in both rhythm and pitch), even when placed far from it — a perilous situation, normally.

Marinuzzi’s merits are exaggerated in the booklet essay. He is described as possibly the greatest conductor of the 20th century, and definitely better in opera overtures and intermezzi than Karajan and Reiner. I think it’s enough to say that he was one of the great Italian conductors of his era and a composer of rare ability and insight. We are lucky to have this recording to prove the latter point.

We are told that he was no Fascist. But I imagine the case is more complicated than that: he maintained an active professional career in Italy throughout the Fascist era, and he brought the La Scala orchestra to Berlin in 1941-42 for some recordings (on the Telefunken label) that are so prized now that they were re-released commercially in 2013, though of course by the early ’40s Nazi forces had seized western Poland, occupied northern France, and invaded Denmark and Norway, and Italy was siding with Germany. As I said, I decided to try, in my remarks above, to evaluate this opera (from 1932) on its own merits while also raising the question of its political context.

By the way, there is mention in Wikipedia of a Decca recording of Palla de’ Mozzi starring Anna Netrebko. So far as I can tell, this is an error. The Dynamic recording is the first and only. The booklet contains the libretto in Italian and mostly comprehensible English, making the work easy to get to know — and, I found, to love.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is an expanded version of one that he first published in American Record Guide; it appears here with kind permission.

A note that theater companies and critics have had to deal with the issue of high art during the Fascist era of the ’20s and ’30s often — if they are willing to bring up the uncomfortable fact that one of greatest playwrights of the 20th century, Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936), was a Mussolini sympathizer. There is some debate how firm a follower he was. Was Pirandello a true believer? Some critics feel that the writer paid lip-service to Fascism because he and his theater company needed government funding in order to have his plays produced. Still, there is no getting around his public allegiance to the cause, whatever he thought that was.

In 1924, Pirandello sent this self-destructive telegram to Mussolini:

[…] Recordings Opera Album Review: From Fascist Italy — With Love? An opera from Fascist Italy, Gino Marinuzzi’s memorable Palla de’ Mozzi receives a splendid world-premiere recording. Should you listen despite its pedigree? https://artsfuse.org/260734/opera-album-review-from-fascist-italy-with-love/ […]