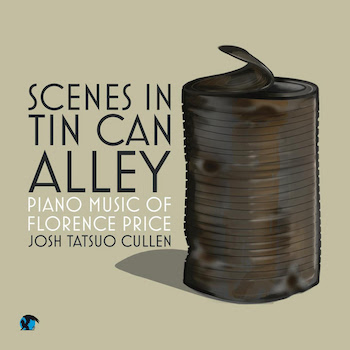

Classical Album Review: Florence Price’s “Scenes in Tin Can Alley”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Symphonic music wasn’t composer Florence Price’s strong suit. Rather, she was much more at home working in smaller forms or for her own instrument.

Few figures have benefited more from the recent surge of interest in music by composers of color than Florence Price. In recordings, performances, and print, the Arkansas-born, Boston-trained, Chicago-based musician is getting a long-overdue rehabilitation. The latest installment in the continuing effort comes courtesy of pianist Josh Tatsuo Cullen, with a survey of some of Price’s piano music.

It’s a timely addition to the Price discography. The most high-profile releases of her music of late have been of orchestral works; one of those — the Philadelphia Orchestra’s recording of her Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3 — took home a Grammy award. Welcome as that recognition is, it perhaps doesn’t do Price full justice: symphonic music wasn’t her strong suit (a fact that’s paradoxically emphasized in the Philadelphians’ excellent performances). Rather, she was much more at home working in smaller forms or for her own instrument.

Here, Cullen plays seven pieces Price composed between 1926 and sometime in the ’40s. (Dating her music can be notoriously difficult. These compositions were discovered in 2009 at the composer’s summer home after her death.) To a score, these selections winningly showcase the composer’s musical strengths: natural tunefulness, the thorough development of short musical ideas, idiomatic (and often quite virtuosic) keyboard writing among them. Unlike in some of Price’s larger works, nothing feels structurally imitative or forced. Also, her harmonic language in here, though firmly tonal, is anything but derivative or staid. Instead, there’s a good bit of variety on offer.

In the eponymous Scenes in Tin Can Alley (from 1928), the exuberant figures of the opening movement, “The Huckster,” contrast strongly with the soulful, slightly bluesy turns of the concluding “Night.” The central “Children at Play,” with its blend of rhythmic activity and stasis, forms a wholly logical bridge between those two scenes.

Price’s Three Miniature Portraits of Uncle Ned follows a similar trajectory: a spry first movement is followed by a striding central one; afterwards, the serene, hymnlike finale caps the work nobly.

The remaining five pieces, however, don’t share such formal templates — at least not as obviously.

Thumbnail Sketches of a Day in the Life of a Washerwoman paints four different scenes: “Morning,” “Dreaming at the Washtub,” “A Gay Moment,” and “Evening Shadows.” While the first two are relatively quiet, the third is syncopated and vigorous — here Price’s writing reflects the best “Juba” movements in her symphonies — and the finale ends not with solace but in searching harmonies and a series of rhetorical gestures.

Meanwhile, 1942’s Village Scenes are, broadly speaking, charming, if sentimental miniatures. Tolling figures conjure the opening “Church Spires in the Moonlight,” while “A Shaded Lane” unfolds sweetly. “The Park” is predictably lively and playful.

Pianist Josh Tatsuo Cullen — an accomplished, sympathetic advocate.

The disc’s most abstract inclusion is the set of five Preludes Price wrote between 1926 and ’32. They’re a bit hard to place, stylistically — little in them sounds like classical or popular fare from those years — but the finale, with its giguelike rhythms and minor mode domination, anticipates Price’s later symphonic finales.

Rounding out the album are the lush, Ravelesque Clouds and the boisterous, folksy Cotton Dance.

In all of these works, Cullen proves an accomplished, sympathetic advocate: he clearly knows his way around and is comfortable with this music. That the program holds together so well is a testament to both his artistry and musical intuition (the liner notes point out that the pianist chose the track list because each piece was meaningful to him for fundamental reasons). One mightn’t mind a bit more — at 50 minutes, the recording is on the brief side — but there’s never the sense of being short-changed by the performances.

While the keyboard’s recorded tone is a bit bright, the instrument always sounds full-bodied and never becomes brittle. To be sure, the disc’s engineering ensures that the music’s many busy passages always speak lucidly.

In all, then, an excellent “way in” to Price at her freest and best. Recommended.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Blue Griffin Records, Florence Price, Josh Tatsuo Cullen