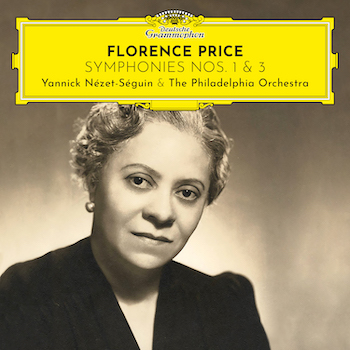

Classical Album Review: Florence Price’s Symphonies nos. 1 & 3

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Florence Price’s voice and the richness and complexity of an almost entirely neglected body of symphonic music by Black American composers can be heard in this excellent recording.

Recordings of Florence Price’s symphonies by top-tier professional orchestras have been a long time coming. Granted, this music has been kept alive of late by the admirable efforts of some regional and international ensembles (particularly John Jeter and the Fort Smith Symphony in Arkansas). But given Price’s reputation as the country’s first important African American woman composer, her output surely deserves wider advocacy.

Recordings of Florence Price’s symphonies by top-tier professional orchestras have been a long time coming. Granted, this music has been kept alive of late by the admirable efforts of some regional and international ensembles (particularly John Jeter and the Fort Smith Symphony in Arkansas). But given Price’s reputation as the country’s first important African American woman composer, her output surely deserves wider advocacy.

Enter Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra, who are now helming the first recorded cycle of Price’s symphonic works by a major American orchestra.

The results of their first release, which pairs her Symphonies nos. 1 and 3, are revealing.

To be sure, Price’s music has never sounded better. The Philadelphians’ playing is technically impeccable, carefully balanced, and smartly shaped. For warmth of tone, continuity of sound, and delicacy of phrasing, one can hardly imagine either piece being more flatteringly presented.

At the same time, the excellence of these performances highlight some of the weaknesses of Price’s technique.

Chief among them is that, while she was a gifted miniaturist, Price was no natural symphonist.

Take the E-minor Symphony no. 1. Written in 1933 and premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Frederick Stock, it’s plenty ambitious, lasting nearly 40 minutes.

Yet at least a third of that duration is digressive — most of it, in fact, the fault of the first movement. Here, Price follows symphonic sonata form to a T: there are contrasting subjects in two key areas, an exposition repeat, a busy development, a recapitulation of the opening materials, and a blazing coda. On paper, then, a textbook symphonic movement.

In performance, though, the exposition repeat proves superfluous. The development lacks direction and shape: it ambles along to the recapitulation, but there’s no discernible musical reason for why or when we arrive there. What’s more, Price’s enthusiasm for placing rallentandos and fermatas at the ends of phrases becomes tedious and undercuts the music’s momentum.

There’s a similar strictness found in the finale, which is a kind of whorling jig that is squarely phrased and, likewise, goes on for a bit too long.

Having said all of that, Price’s First is no flop. Quite the opposite: apart from the overlong first movement, it’s a beguiling essay. Her orchestrations, if not always inspired, display — even in that meandering first movement — an ingenious ear for color (like the appearance of chimes and celesta in the development) and texture (vaguely Ivesian clarinet shadow lines pop up periodically).

Best, once you get to the inner movements — which draw more clearly on her African American heritage and experience as a church musician — the piece takes on a different cast entirely.

The second movement, with its call-and-response structure, strong contrast of thematic ideas, and creative scoring, is beautiful: in the present recording, you can hear all the moving melodic lines. And, despite the occasional busyness of the registrations, the Philadelphians’ woodwind solos are luminously done.

For the third movement, Price drew on the African Juba dance. Agile and fresh, this music offers lots of repetition but enough variation in the orchestration so as not to become redundant, as well as spry syncopations and layers of rhythmic complexity throughout.

The Symphony no. 3 is, broadly speaking, more elegantly scored — the woodwind writing is again exceptional — though still marred by certain of the First’s shortcomings (namely some choppy phrasing and a continued penchant for fussy tempo manipulations).

Again, it’s the middle movements that really sell the piece. Here, the sweet, lyrical second movement grows into something quite radiant, with conspicuously effective writing for brasses and celesta around the midpoint.

The Third’s Juba is plenty jaunty and highlighted by a sultry, habanera-like Trio with a solo xylophone. In the finale, Price again wrote a driving giga, though, in this one, some Spiritual-like turns of harmony — and a reprise of the first movement’s opening chorale — keep things from becoming too predictable.

Conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Photo: Hans Van Der Woerd

What to make of it all?

First, these are singular symphonies. No, they’re not perfect. But their charms are considerable and, when placed in the context of pieces like William Levi Dawson’s “Negro Folk Symphony” or William Grant Still’s “Afro-American” Symphony and “Song of a New Race,” the singularity of Price’s voice and the richness and complexity of an almost entirely neglected body of symphonic music by Black American composers begins to emerge.

Related to this, the strongest writing here comes in the Symphonies’ central movements. The way in which Price personalized these scores to reflect her own distinct heritage is, fundamentally, no different than what Berlioz or Brahms or Mahler did in their own efforts in the genre. Her adaptation of her source materials give these scores their unique flavor, and I know of no other composer who handled such content in the ways Price did.

Finally, Nézet-Séguin and his orchestra prove compelling advocates for Price’s music. While their readings might, occasionally, want for a bit more rhythmic edge, these interpretations fulfill the maxim that great musicians redeem a host of (technical and structural) compositional shortcomings. The Philadelphians play this music with purpose, and it shows.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Deutsche Grammophon, Florence Price, Philadelphia Orchestra