Book Review: “The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon” — A New Chapter in the American Story?

By Bob Katz

What a cruel hoax: the middle-class suburban lifestyle, a proud achievement of postwar America and the envy of peoples throughout the world (in no small part due to Mad Men glamorization), contains the very seeds of our demise. If demise is where this is heading.

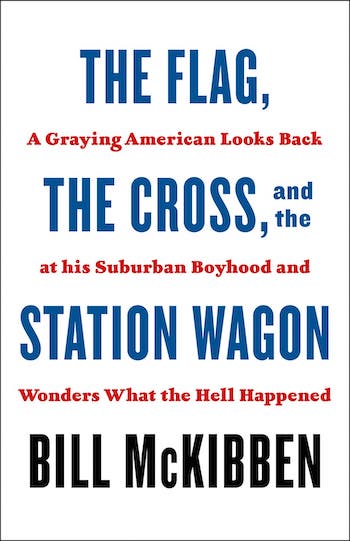

The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon by Bill McKibben. Henry Holt and Co., 240 pages, $27.99 (hardback).

It would be a mistake to review Bill McKibben’s latest work, The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon, as if it were but another entry in the high-stakes publishing sweepstakes to capture the zeitgeist and bring home the gold. His sights are set higher than that.

Subtitled “A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened,” McKibben attempts with this, his 19th book, an audacious mashup of memoir, history, theology, socioeconomics, climate science (of course), and a stab at a unified theory of the country’s descent into a demoralized state. Underlying this is his fervent wish, as writer and activist, to add a new next chapter to the American story, one that could yet make it turn out all right.

The book’s opening section, “The Flag,” begins with an account that originally appeared online in the New Yorker as “The Second (and Third) Battle of Lexington.” (McKibben’s first job fresh out of college was as a New Yorker staff writer. Among his many heresies, perhaps foremost among them, is that he long ago opted to forego the straight and narrow of single-minded literary ambition, despite that fast track start, and chose instead to go all-in as an activist on the environmental issues he writes about so eloquently.)

Lexington, the Boston suburb where McKibben was raised, fits the purposes of this book with straight-from-central-casting perfection. Having grown up in the very town where the American revolution began, McKibben seems to be following a script that called for a young man like him to carry on the lessons of the revolution. Such grandiose self-importance, thankfully, is not his style. But it wouldn’t be altogether ridiculous if it were.

During high school, he had a summertime gig giving narrated tours of the famed Battle Green. McKibben’s a sleek writer and his glee is palpable as he recounts regaling tourists with stirring tales from the events of April 19, 1775: Revere’s daring midnight ride from Boston, the brave resolve of the outmanned Minutemen, the unplanned shot that sparked the battle, the rout by the British that was soon reversed in nearby Concord. “I told the same old story over and over again,” he writes, “until it was deeply imprinted on me. And I never lost that sense of connection to an apparently noble past.”

McKibben lovingly characterizes his Lexington boyhood. “A single big maple spread its branches over the front lawn and the driveway, dropping leaves on the maroon Plymouth that carried my father on his daily commune. We were as statistically average as it was possible to be, a near perfect example of the white American middle class rocketing to prosperity…. We lived, and this is the truth, halfway down a leafy road called Middle Street.”

Two events occurred in Lexington during McKibben’s youth that transformed his feelings about the town and, by implication, the nation.

This first event was a massive 1971 antiwar protest led by the Vietnam Veterans Against the War and featuring the young John Kerry. The historic Battle Green was chosen as the protest’s setting because of its obvious theatricality. (Identification with the valor of the American revolution is a tactic promiscuously used, and misused, by the left and the right; a topic for another day.) Some 458 protesters, including McKibben’s otherwise centrist father, were arrested for disturbing the peace.

“This was the most exciting and dangerous place I’d ever been,” McKibben recalls, giving a hint of his trajectory. He was 10 at the time.

The second event occurred the same year. But unlike the highly publicized VVAW protest, McKibben knew nothing about it until he began researching this book. A proposal to build a low-income housing complex had been overwhelmingly approved by Town Meeting, the local legislative body, by a vote of 127-56. A backlash quickly ensued and disgruntled neighbors launched a campaign to reverse this decision. This referendum passed by nearly a 2-1 margin.

“Let’s be real,” McKibben reflects. “Right now all that talk about equality, and farmers standing up to kings, and so on — the talk that was so appealing to me when I was a guide and which still stirs me when I read it — is hard to take seriously in a country that has turned out as unequal as the one in which we live.”

That American history is strewn with contradiction, even outright hypocrisy, is far from breaking news. So why does McKibben harp on this? Probably because the story he is telling of Lexington is inextricably his story, and he desperately wants it to turn out all right. A more hopeful next chapter needs to be written. It cannot be fiction.

Bill McKibben, author and activist. Photo: Nancie Battaglia

From discussion of “The Flag,” McKibben moves to a consideration of “The Cross.” “I’m going to try something in this chapter,” he humbly acknowledges, “that I’m not sure I can pull off.”

Growing up, he faithfully attended the Congregationalist Hancock Church situated by the Battle Green. Spring break service trips to the rural south, after-school stints helping out at the Fernald School for the Retarded (that’s what it was called), and spirited retreats resounding with “Kumbaya.” As a Harvard undergrad, he was a regular at early morning Chapel services. At the New Yorker, McKibben spent an hour each day copying out the Gospels by hand. Huh? “I don’t know how it came into my head,” he writes, “except for some image of monks by candlelight copying manuscripts with quills.”

That tells us something. Monks laboring by candlelight is not an image that appeals to everyone. As McKibben has clung to those Battle Green tour guide sentiments — in hopes of salvaging some actionable essence — so he yearns to commandeer religion for progressive political organizing. It doesn’t come easily. The strain shows.

According to McKibben, the shift in American Christianity from the earnest Hancock Church of his youth to flamboyant megachurches like Willow Creek and Saddleback has less to do with rightward politics (although clearly it is that) than with a fundamental shift from communitarian ideals rooted in the spirit of egalitarianism to the kind of virulent hyperindividualism where parishioners solemnly pray that their business deals succeed and their children get admitted to a favored college.

One gets the sense that McKibben, under serious time-clock pressure, is intent on mobilizing every asset, no matter how ill-suited or unwilling. Regarding his continued hope that American religion may someday rise up to fulfill its potential as outside agitator and countercultural force, all I can say is: wouldn’t it be nice.

“The Station Wagon,” in McKibben’s telling, is where the rubber meets the road. Suburbia, given its crucial role in both the boom and bust of the American story, is the place (and demographic) he’s most avid to understand. And expose. And undo.

We return to his suburban upbringing (also mine, by the way, and possibly yours). Reminiscing about the modest two-story home he shared with his parents and brother, its skinny backyard with a tree fort, his bicycle explorations of newly carved streets sprouting newly built homes, McKibben sounds as carefree as Huck on a raft floating down the mighty Mississippi. But treacherous currents were churning unseen, just around the bend.

McKibben pulls no punches in dissecting the alleged sins of contemporary suburbia. Lexington is not spared. The house that his parents purchased for $30,000 in the ’60s sold recently for one million dollars. It was then promptly torn down and replaced by a structure that “looks like a smallish junior high school crossed with a medium-security prison.” Larger homes, he asserts, undermine our sense of community in nefarious ways, creating more distance between neighbors, exacerbating economic inequality, ratcheting up per household energy demands, and swelling investment in private property at the expense of public expenditures.

“We consume more, and we do it more privately,” McKibben laments. “That is what the suburban experience amounts to in purely physical terms.”

Indeed, the vast wealth accumulation resulting from home construction and appreciating property values becomes the critical cornerstone of his overarching theory of “what the hell happened.” The intensifying of militant individualism, the shirking of collective responsibilities, the rise of political conservatism, the aggravation of racial disparities and other injustices, the circling of the wagons and doubling down on willful myopia, all this and more are attributed to the bloblike sprawl of suburbia. McKibben contends, somewhat astonishingly, that the only modern developments of comparable economic impact are the ascent of China and the rise of the Internet.

And what a cruel hoax: the middle-class suburban lifestyle, a proud achievement of postwar America and the envy of peoples throughout the world (in no small part due to “Mad Men” glamorization), contains the very seeds of our demise. If demise is where this is heading. I did wonder why exactly McKibben believes that transformation of a suburban culture and economy so massively entrenched on so many levels is realistically possible. But we’ve all heard enough smart talk about what cannot be done.

McKibben is not quite ready to concede. Throughout the book he drops tonal hints that the “third” battle of Lexington (wherein a community of decent folk voted in direct contradiction to its professed values) may not be the last. A “fourth” battle, galvanized by the climate crisis, might yet make the story come out all right.

That’s a fight McKibben is prepping for (see ThirdAct.org). This book, straining to arrive in time, is his midnight ride.

Bob Katz is author of five books, including the nonfiction Elaine’s Circle (recently re-issued, see link) and the novel Third and Long. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Slate, and many other publications.

Tagged: Bill McKibben, Bob Katz, Climate Change, Henry Holt and Co