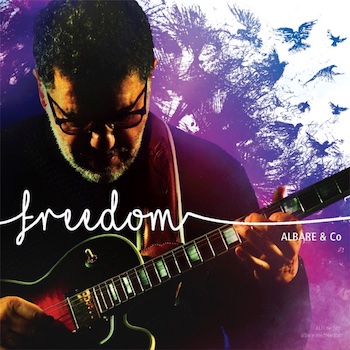

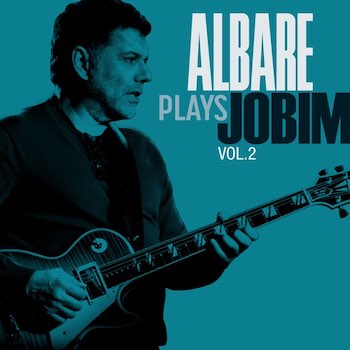

Jazz Album Reviews: Two From Guitarist Albare — One Sedately Traditional, the Other More Satisfyingly Adventurous

By Allen Michie

Albare Plays Jobim: A Tribute to Antonio Carlos Jobim is a traditional Brazilian offering, content to offer soothing Bossa Nova rhythms; Freedom is more unconventional, merging Brazilian beats with jazzier improvisations.

Albare, Freedom (Alfi), Albare Plays Jobim Vol. 2 (Alfi)

It is increasingly difficult to become a resident or citizen in countries around the world. It is as if nations see themselves defined more by who they aren’t rather than who they are. Musically, however, perhaps no other nation has been more welcoming to outsiders than Brazil. Musicians have incorporated their voices into the seductiveness of Brazil’s rhythms with gusto, particularly since the Bossa Nova craze of the ’60s. Brazilians themselves, thankfully, don’t seem too hung up about “authenticity.” Excellent Brazilian music is always welcome — no matter who is making it.

It is increasingly difficult to become a resident or citizen in countries around the world. It is as if nations see themselves defined more by who they aren’t rather than who they are. Musically, however, perhaps no other nation has been more welcoming to outsiders than Brazil. Musicians have incorporated their voices into the seductiveness of Brazil’s rhythms with gusto, particularly since the Bossa Nova craze of the ’60s. Brazilians themselves, thankfully, don’t seem too hung up about “authenticity.” Excellent Brazilian music is always welcome — no matter who is making it.

Jazz guitarist Albert Dadon, better known as Albare, was born in Morocco, raised in Israel, and spent his formative years in Paris. He moved to Australia in 1983, where he has become a major force on the Australian jazz scene, assembling an excellent roster of like-minded musical collaborators. He’s been a businessman, concert promoter, philanthropist, and lately the owner of the Alfi record label. His early influences (Django Reinhardt and Wes Montgomery) are still evident in his playing, but so far in the 2020s he has explored Brazilian music in depth, particularly the compositions of Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Two of his latest albums, Albare Plays Jobim Vol. 2 and Freedom, both on his Alfi label, offer different approaches to the Brazilian groove. Albare Plays Jobim Vol. 2 is a follow-up to 2020’s successful Albare Plays Jobim: A Tribute to Antonio Carlos Jobim. It’s a traditional Brazilian offering, serving up the soothing Bossa Nova rhythms that evoke the balmy beaches of your vacation daydreams. This year’s Freedom is more adventurous, merging Brazilian beats with jazzier improvisations and complex rhythms.

Freedom is the stronger disc because of the variety of its musical textures. The session is informed by Latin American music but is in no way limited to it. All the compositions are by Albare, either alone or co-composed with pianist Phil Turcio. They are perfectly attuned to one another’s melodicism and tonality after 30 years of playing together. They make a very comforting and satisfying sound, knowing when to support one another but also when to stay out of one another’s way. The chords never pile up, even when both are comping behind other soloists. They blend as co-producers as well, creating a warm recording with plenty of presence and depth.

The opening track, “Freedom,” is an up-tempo samba with a guest solo from Albare’s friend Randy Brecker. Drummer Felix Bloxom keeps it loose under Brecker’s solo and tight under Albare’s, varying the texture and feel. There’s even more subtlety on “Adues,” which begins with a very slow introduction then transitions to a bright up-tempo samba. Phil Rex’s acoustic bass is richly recorded to reveal the resonances from deep inside his instrument, and Albare plays lightly, rarely bearing down on the strings.

The guest horn soloists, Brecker and saxophonist Ada Rovatti, brighten things up and provide some sonic diversity. “La Fiesta,” another up-tempo samba, offers artful overdubbing that simulates the sound of a horn section. The high tones of Rovatti’s soprano effectively contrasts with the super-low sounds of Rex’s bass.

“Lost Compass” reunites Brecker and Rovatti, and on record as in life (they’re married!), they harmonize together beautifully. Albare plays with a fuzzy rock sound behind the horns, which brings out a very different kind of melodicism in his solo. The lighter soft touch is gone — we are given more sustained notes, vibrato, and effects. He’s not going to put Mike Stern out of work here, but it adds some welcome diversity. Bloxom shows his adaptability on drums, opening up the straightforward composition to some rhythmic complexity.

Albare also changes his guitar tone on “Love Is Always,” cranking up the reverb. The approach to his solo seems to change with the altered tone here, as it did on “Lost Compass” — he flitters across the chord changes like the flying birds on the album cover, not settling into exploring linear melodic lines as he does on the other tracks by way of his traditional Jim Hall/Kenny Burrell sound.

Albare also changes his guitar tone on “Love Is Always,” cranking up the reverb. The approach to his solo seems to change with the altered tone here, as it did on “Lost Compass” — he flitters across the chord changes like the flying birds on the album cover, not settling into exploring linear melodic lines as he does on the other tracks by way of his traditional Jim Hall/Kenny Burrell sound.

Other sambas include “Shimmozle,” with Albare playing acoustic guitar and adding some pastel flamenco colors. It’s worth hearing twice so you can go back and appreciate Turcio’s spare and focused accompaniment. “Sunny Samba” is just that, with Albare adopting a breezy Wes Montgomery-style California groove. You might find this one on a cruise ship poolside playlist but, if you listen carefully, Albare and Brecker will repay the effort with substantial if conventional solos.

Other tracks explore rhythms informed by, but not limited to, bossa nova. “Randy Makes Me Smile” is a swinger, with Albare back to his signature tone, Rovatti killing it on tenor, and Brecker playing with a fat sound like Art Farmer in his prime. “Sketchers” is a slow ballad, exploring the spaces opened up by the resonance of the bass, which is allowed to linger and naturally sustain. “New Expectations” is in 7/8, and it’s another example of that simpatico sound that Albare and Turcio have established. This time Albare plays with more of the Pat Metheny sound and groove. We finally get a full piano solo from Turcio; it would have been good to hear more from him throughout.

If only Albare Plays Jobim Vol. 2 were as varied and engaging. It’s lovely music in small doses but, taken all at once, it’s a snoozer. This is a much more commercial affair, featuring strings sweet enough to give you diabetes. “Caminhos Cruzados” even adds some vibraphone for the full Muzak effect. The guitar solos reward close listening, but the price you pay is having to endure pianist Joe Chindamo’s sappy arrangements. You could label this an album of background music, but that isn’t being fair to Albare’s accomplished playing. Albare’s Alfi Records isn’t a major label, but the session is richly recorded and beautifully engineered. The guitarist even ponied up for a real (and large) string orchestra. You won’t find anything that sounds better on Sony or Verve, so credit where credit is due.

The great Pat Metheny sideman, drummer Antonio Sánchez, played throughout Albare Plays Jobim: A Tribute to Antonio Carlos Jobim and returns here for two tracks. Sánchez’s prowess is largely wasted on the tracks “Dindi” and “Once I Loved” — the quiet Bossa Nova grooves could have been played by most any studio drummer — but he’s serving the music without a trace of egotism, so good for him.

Brecker is also here as a guest on two numbers. The bright brassiness of the trumpet is a welcome contrast to all the liquid strings. The great Néstor Torres plays flute on two tracks as well, his earthy tone tossing some welcome sand into the sandals.

Jazz guitarist Albert Dadon, better known as Albare, in action.

Albare plays well, as always, but on tracks like “A Felicidade” and the inevitable “Girl from Ipanema,” he isn’t really bringing any fresh thought to the standards. His approach is very Charlie Byrd and Jim Hall. That isn’t an insult by any means, but why not go straight to Byrd and Hall? Only on “Meditation” does Albare play higher and lower on the fretboard, adding a touch more variation, but even this puts slightly different icing on the same cake.

I can’t help but say a few more words about those strings. “Triste” is a gorgeous melody that is unkillable, but Chindamo’s orchestral arrangement is just too much. By the time I got to the penultimate track, “Favela,” I’d had about all I could take. Also, there’s something very ’60s sounding about electric guitar and middle-register unmuted trumpet playing in unison. I see women in pink polyester dresses, go-go boots, and big hair swaying with martinis.

“When I listen back to this album, I don’t hear social distancing, I don’t hear mask-wearing, I don’t hear nasty politics,” Albare writes in the liner notes. “All I hear is a collective love letter to a world much in need of one.” Fair enough, and we can leave it at that.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas.

Tagged: Albare, Albare Plays Jobim Vol. 2, Alfi record label, Allen Michie, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Jazz guitarist Albert Dadon