Book Review: Looking Back, Fondly, on “The Modem World”

By Preston Gralla

This is a great book for anyone who wants to understand the early days of online communications.

The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media by Kevin Driscoll. Yale University Press, 288 pp., $28

Centuries ago, Isaac Newton, who formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, gave his due to the work of those who came before him, writing “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Contrast that with today’s tech startup founders, hoping to launch the next billion-dollar unicorns, who stand on molehills and call themselves far-seeing visionaries. It’s one more piece of evidence that technologists have no memory, always looking only to the Next Big Thing, pretending that nothing that happened in the past has anything to do with their grand visions of tomorrow.

Centuries ago, Isaac Newton, who formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, gave his due to the work of those who came before him, writing “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Contrast that with today’s tech startup founders, hoping to launch the next billion-dollar unicorns, who stand on molehills and call themselves far-seeing visionaries. It’s one more piece of evidence that technologists have no memory, always looking only to the Next Big Thing, pretending that nothing that happened in the past has anything to do with their grand visions of tomorrow.

Kevin Driscoll in his book, The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media, provides a corrective to that. He writes how from the late ’70s until the dot-com boom of the ’90s, dial-up computer bulletin board systems (BBSs) laid the foundation for the Web and social media of today. More than 100,000 of these small-scale networks became, in his words, “the prevailing form of social computing for PC owners.” He explains, “Built by amateurs using off-the-shelf parts and regular telephone lines, this ‘modem world’ offered an open, grassroots alternative to the closed institutional networks sponsored by state agencies, research universities, and multinational corporations.”

He gives the most complete portrayal I’ve yet seen of those BBS days, when the mere idea of communicating with someone via a computer was revolutionary. I lived through it, covered it as a journalist, and watched it ultimately be killed off by the web. They were gentler times, when so much was less at stake in technology than today. No one got rich running the BBSs; no one expected to. That meant more comity, more friendships, and more just plain weirdness. Driscoll does an excellent job of covering not just the technologies that made it all possible, but the tone and mood of the times as well.

That’s not to say all was perfect back then. Far from it. The vast majority of people who ran the BBSs were white, often middle-aged men, and the vast majority of people who dialed into them were as well. Driscoll, doesn’t sugar-coat that, but he also writes about women-only BBSs, and gay and lesbian BBSs, although minorities, in general, weren’t part of the movement.

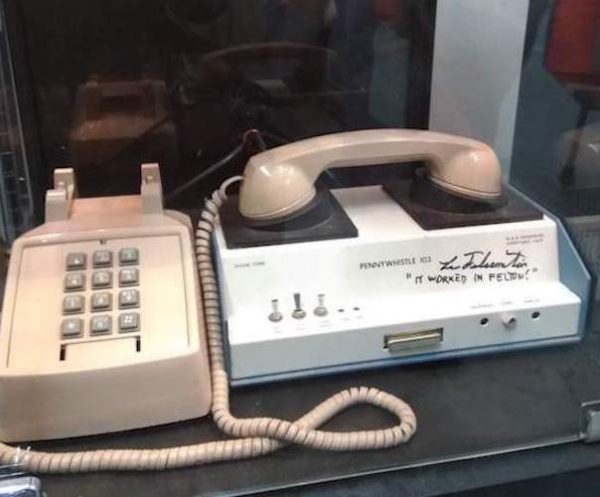

He excels at portraying the growth of technologies that gave birth to the BBSs. For example, he shows how the increasing speeds of modems over time drove not just BBS growth, but what they were used for. In the early days, they were used mainly for online discussions, because early modem connections were so slow and were only adequate for text. Later on, as high-speed modems ruled, file-sharing, and downloading software and graphics files (including, inevitably, pornography) had their day.

An early modem.

For all that, though, the book falls somewhat short on the promise of its subtitle, A Prehistory of Social Media. The BBSs, for all their then-revolutionary communications capabilities, typically didn’t have wide-ranging discussions about every topic under the sun and beyond. Partly that was due to the nature of BBSs. They were typically local dial-ins because in those days you had to pay more for calls outside your area code, and you paid by the minute. So people typically dialed into their local BBS, where people were more likely to look like them and think like them. There were some exceptions, like The WELL, based in Sausalito. But generally, local ruled.

There was a technology called Usenet, though, that really did represent the prehistory of social media. They were discussion groups organized into broad categories such as humanities.* for fine art and literature, misc.* for miscellaneous topics, rec.* for recreation and entertainment, soc.* for social discussions and so on. Each broad topic branched out into countless subtopics, and sub-sub topics, such as rec.arts.movies, or soc.culture.african, and so on. They were the first social media networks. There’s a book waiting to be written about them. But this book isn’t it. (However, BBSs did intersect with Usenet discussion groups, because BBSs provided a convenient onramp to get to them.)

Still, this is a great book for anyone who wants to understand the early days of online communications. And Driscoll is on-target when he compares those early BBS days with today, when Big Tech has swallowed the world. He writes: “Platforms [like Facebook and Reddit] didn’t invent the social use of computer networks. Amateurs, activists, educators, students, and small business owners did. Silicon Valley turned their practices into a product, pumped it full of speculative capital, scaled it, and so far refuses to treat the lives we live with care…I do not expect that new models for online sociality will look exactly like the BBSs did in the 1980s, but the history of the modem world centers on the interests of everyday people, a reorganization of narrative resources from which to envision alternative futures…The internet of today can still become something better, more just, equitable, and inclusive—a future worth fighting for.”

Idealistic? Yes. Impossible? Maybe, maybe not. But we can dream, can’t we?

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.

Nice essay, Preston, and welcome to writing for The Fuse. May there be many more articles!

Thanks, Gerry, and thanks for your help getting me here.

I wanted to push back on the statement that “The BBSs, for all their then-revolutionary communications capabilities, typically didn’t have wide-ranging discussions about every topic under the sun and beyond.”

That doesn’t square with my own experiences on BBSes in the early 1990s. Most boards in my town offered dozens of message bases covering a broad range of topics.

And, yes, BBSes were local, but they could expand their reach by participating in message networks. These networks allowed users on a local BBS to exchange public messages with users on BBSes across town, across the country, or across the world. Fidonet is probably the best known of these inter-BBS messaging networks, but there were tons of others: WWIVnet, Dovenet, and IceNET, to name just a few.

Anyway, thanks for the review. I’m very much looking forward to reading this book.

Good point about Fidonet, in particular; you’re right about that. Usenet newsgroups, I believe, were even better because they had a broader range of topics and deeper engagement. If you read the book, post here what you thought of it. — Preston