Book Review: “The Archeology of a Good Ragù” — A “Bipolar” Memoir

By Vincent Czyz

Rather than the usual story of assimilation, John Domini gives us a deftly written narrative of return, self-discovery, disillusionment, personal metamorphosis, and ultimately, rejection.

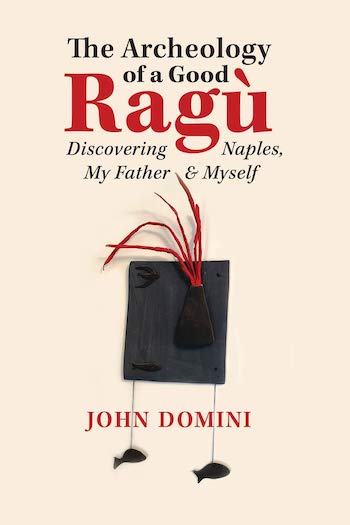

The Archeology of a Good Ragù: Discovering Naples, My Father and Myself by John Domini. Guernica World Editions, 285 pages.

Back in the early 1990s, I had a brief correspondence with journalist and author Gay Talese. I’d been reading his memoir, Unto the Sons, a 635-page tome described as “an Italian Roots” by Washington Post Book World. In our exchange of letters — actual pen and paper — Talese and I lamented the dearth of books about the Italian-American experience (despite the Polish surname, I’m three-quarters Italian). At the time, we could come up with only three such books: Pietro Di Donato’s Christ in Concrete, a novel that has not aged well; Mario Puzo’s Fortunate Pilgrim; and Talese’s memoir. (For some reason neither of us acknowledged The Godfather, the novel that lofted Puzo into the literary stratosphere.) A number of books by or about Italian Americans have followed Talese’s 1992 memoir, including Salvatore Scibona’s critically acclaimed The End, a 2008 National Book Award Finalist. Also worthy of note: Tina De Rosa’s Paper Fish, which, initially released by an obscure indie in Chicago, didn’t gain much traction until it was reprinted in 1996 by The Feminist Press.

Published last May, John Domini’s The Archeology of a Good Ragù: Discovering Naples, My Father, & Myself, doesn’t quite fit the mold of any of the aforementioned. Rather than describing the experience of his father (or himself) in the country to which his father immigrated, he rediscovers himself (and his father), by returning to Italy. In this sense, the book is probably unique.

Distraught, his interior landscape devastated by divorce, and approaching middle age, Domini decides on a complete change of scenery. “In order to get a handle on the rest of my life,” he writes, “I needed to know my father and his city.” Domini arrives in Naples “as badly adrift at 40 as at 20: first a kid who’d never had a steady girl, then a man who’d somehow left his wife unsatisfied.”

“Build your cities on the slopes of Vesuvius!” wrote Nietzsche in The Gay Science, exhorting his readers to “live dangerously.” And, as Domini points out, Neapolitans did. Naples, as it happens, is nestled between two volcanoes — Vesuvius, which buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in a rain of ash in 79 AD, and Campi Flegrei (Burning Fields).

Central to the memoir are two photos of Domini’s father as a young adult. In the first, Vincenzo Vicedomini, who would later truncate his surname, is at a picnic. Sitting atop a table, he’s “hanging loose, ready to leapfrog across the countryside. A heartthrob, not an ounce of fat on him, he grinned hugely, his hair losing its comb.” The second photo is very different. In this one, taken several years later on a street in Naples, Vincenzo is “wary. Switch out the face in Photoshop, and you’ve got a still of some tightly coiled screen urbanite, Johnny Boy in Mean Streets or Omar in The Wire.” There’s the suggestion that one hand, deep in a pocket, is seeking the reassurance of a knife. Solving the mystery of what happened between these two photos — how Vincenzo went from carefree youth to “urban blade” — seems the key to understanding his father and, in some sense, himself.

One of the things that happened was the Nazi invasion of Italy in 1943. Naples revolted in the little-known but brutal “Four Days of Naples” — a Neapolitan victory — and the Allies occupied the city later that year. Though Vincenzo was caught up in these momentous events, he was mostly close-mouthed about the roles he played and the hardships he endured. It’s only through scraps of family testimony and some rare patriarchal confessions that Domini pieces together what turned his father into the street-tough he saw in the second photograph.

This is one thread in the memoir. Another deals with Domini’s efforts to reinvent himself, to go from a writing career in the corporate world — marketing, advertising, public relations — to one in academia and the arts, which primarily meant writing fiction (he went on to publish a trilogy of novels about Naples, among other book-length fictions). The transition is nothing if not turbulent, and he’s reduced to making a living piecemeal: “Here was $400 for a piece in the Oregonian, here $500 for an Arts Commission grant, and if I picked up a pair of Comp classes, $5400 each — blessed is he.” He characterizes himself during this phase as “a skipping stone on the American economic diaspora.”

If the Mafia (aka the Camorra, malevita [bad life], the mob) is a dark rumor in the backrooms of America, it’s front and center in Naples. In America if you leave mobsters alone, they’ll probably leave you alone. As Domini makes clear, that’s not how it works in Italy, especially in Naples. One of his cousins, a doctor, was forced to cut them in on his physical therapy clinic and to treat Mafiosi with wounds typical of their violent trade. Another cousin, who gave up “his gift for music” along with his dream of being a pianist, repurposed himself as an engineer. After the mob “snatched away” a lucrative business venture, he abandoned Naples itself. If Steve Jobs had grown up in Naples, Domini speculates, “the man who gave us the laptop and the iPhone winds up doing auto repair.”

Author John Domini. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Pulled between his Italian heritage and his American upbringing, fantasizing about a life in Naples, about becoming the much-romanticized artist abroad, Domini becomes bipolar, so to speak. Rather than the usual story of assimilation, Domini gives us a deftly written narrative of return, self-discovery, disillusionment, personal metamorphosis, and ultimately, rejection: by the end of the book, Domini concedes, “the city could do no more for me.”

What had it done for him? One answer might consist of an analogy: To find out whether a newly built boat is watertight, it must be launched. Naples was the sea when Domini embarked on a new life at the age of 40, and he sprang a few leaks — failings as a writer, as a father, as a Neapolitan-wannabe. His naivete vis-à-vis the latter is summed up by the “weary growl” of a love interest: “You have no idea how difficult it is in Naples.” Domini, dispensing with the figurative, credits his ancestral hometown with instructing him in romance, corruption, and vulnerability (“all could be lost, at any moment, around any corner”).

Formally speaking, The Archeology of a Good Ragù twists the conventions of memoir into startling shapes. Chronology is something implied, hinted at, rather than a steel undergirding. The narrative is episodic, impressionistic. Time is malleable and Domini travels it at will. There’s sleight of hand — faces, names, and events disappear only to reappear later. Patterns coalesce, unbraid themselves, return in altered form. The city itself, with its breathtaking sea vistas and ugly criminal elements, its glorious past and uncertain future, its Mediterranean allure and sobering realities, is a nexus of contradictions. All of this comes through in Domini’s writing, as do the complexities of family dynamics, the exigencies of war (Italian partisans kill a Nazi for his boots), and the struggles of drug addiction embodied in Domini’s long-distance relationship with his daughter.

Near the beginning of the book, Domini tells us Naples’s founding myth is bound up with the fate of one of the sirens: “It was Partenope, who, after Odysseus heard her sing but sailed on by, couldn’t bear the disgrace” and threw herself into the sea. Naples sprang up where the body supposedly washed ashore. Hence, at one point, Domini writes, “The Siren City kept up the only song I could hear.” This book is in many ways an ode to his father, but it’s also Domini singing back to Naples.

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction that was awarded the Eric Hoffer Award for Best in Small Press; The Christos Mosaic, a novel; and The Three Veils of Ibn Oraybi, a novella. He is the recipient of two fellowships from the NJ Council on the Arts, the W. Faulkner-W. Wisdom Prize for Short Fiction, and the Truman Capote Fellowship at Rutgers University. His work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Tin House, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Copper Nickel.

A note of admiration for John Domini’s 2014 collection of essays & criticism, The Sea-God’s Herb, with a particular recommendation for its opening piece, “Against the ‘Impossible to Explain'”. “… the trouble with contemporary criticism can be understood as largely a problem of degree. Too many critics follow the money, uncritically … Not enough critics will cock an ear to any noise beyond New York or take time to sample twenty pages of a novel that comes out of nowhere and demands extra effort.”