Book Review: “Hemingway’s Widow” — Not a Pretty Story

By Roberta Silman

We now have a book that virtually closes the circle on Hemingway’s women, a biography that will be treasured by the author’s fans and scholars.

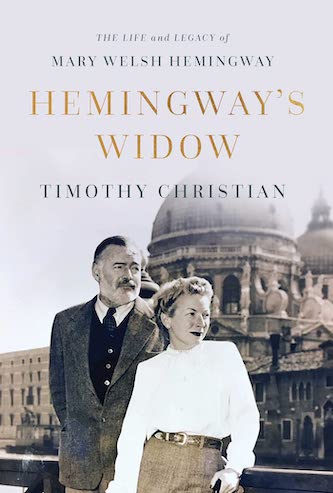

Hemingway’s Widow: The Life and Legacy of Mary Welsh Hemingway by Timothy Christian. Pegasus Books, 464 pages, $29.95.

In May 1944 Ernest Hemingway arrived in London to do some war reporting for Collier’s Weekly on the invasion of France. He was only 44 years old but well known for his novels and his larger than life personality. His third marriage to the journalist Martha Gellhorn, with whom he seemed to be in a life or death competition about everything that mattered, was a mess. Martha was on her way to London, too. But Ernest’s brother Leicester was also in the city, working on a film crew with Robert Capa. To distract Ernest, he arranged that he and his brother would be at the famous White Tower restaurant on a night when Mary Welsh, a correspondent for Time, would be there with Irwin Shaw who, though married, was known as the sexiest man in Europe. Mary was still married to her first husband, Noel Monk, but that marriage, too, was falling apart. The die was cast.

In May 1944 Ernest Hemingway arrived in London to do some war reporting for Collier’s Weekly on the invasion of France. He was only 44 years old but well known for his novels and his larger than life personality. His third marriage to the journalist Martha Gellhorn, with whom he seemed to be in a life or death competition about everything that mattered, was a mess. Martha was on her way to London, too. But Ernest’s brother Leicester was also in the city, working on a film crew with Robert Capa. To distract Ernest, he arranged that he and his brother would be at the famous White Tower restaurant on a night when Mary Welsh, a correspondent for Time, would be there with Irwin Shaw who, though married, was known as the sexiest man in Europe. Mary was still married to her first husband, Noel Monk, but that marriage, too, was falling apart. The die was cast.

Ernest claimed he fell in love with Mary at first sight. Mary was not so sure. Still, she was in her late 30s, and Irwin had a wife back home. So, after a few months of totting up Ernest’s assets and liabilities, Mary entered into one of the most transactional marriages I have ever read about — a marriage that would catapult her to a fame she never could have imagined as an only child from a provincial town in Minnesota, and that would also be the cause of her descent into an ignominious death.

In keeping with what has become a “Hemingway craze” fueled by the Ken Burns documentary series on the author’s life (which I reviewed last year), we now have a book that virtually closes the circle on Hemingway’s women. Hemingway’s Widow is the story from Mary’s perspective of the last third of her husband’s tumultuous life. When there was a lot of evasion and double-talk about what was really happening, and why. When the effects of those concussions Hemingway suffered were not completely understood. When his inheritance of mental illness was downplayed, and his paranoia at the end of his life was attributed to his penchant for “embroidering.” Perhaps most important, when his tragic suicide could not be faced squarely and was presented as an accident. Thus, this biography will be treasured by Hemingway fans and scholars.

It is not a pretty story, though, especially for those of us who admire Hemingway’s work and who found the Burns series quite moving in its empathy for Ernest as a man. Because Mary is often as unlikable as Ernest could be. In some ways he had finally met his match in this fourth marriage, and there are times when they seem to be equals. But her ability to stand up for herself also brought out the worst in both of them, and then he got the upper hand. There were frequent fights. often after hard drinking, and the inevitable reconciliations, which sometimes read like a B movie. For all their intelligence and talent and generosity, Ernest and Mary were also extraordinarily childish and petty and stingy. These unpleasant characteristics surface in their relationships with Ernest’s children and their friends and acquaintances and the help at Finca Vigia, where they lived. So the question one has to ask is: Why did this marriage last until Ernest’s death?

Mary Welsh, in uniform as a war correspondent. Photo: Wiki Common

Timothy Christian answers that question in the book’s Prologue, and it reads like a Hemingway short story about an anonymous couple stuck in a small town in Wyoming when the pregnant wife hemorrhages from a burst fallopian tube. Doctors cannot find a vein to inject the needed plasma and blood and are about to give up on both mother and child when the husband takes over and is able to insert the needle intravenously, thus saving the mother’s life. That husband and wife were Ernest and Mary. After this ectoptic pregnancy they would never have a child, which they badly wanted. But Ernest had saved her life and Mary would never forget it. That episode in 1946 created an unbreakable bond between them.

This is a long biography, beginning with Mary’s story as a feisty young woman who comes to London in the late ’30s as a freelance correspondent. Scenes of London during World War II are exciting and interesting as we see her grow to become a respected reporter, no mean task for a woman at that time. We also see her become more confident, both intellectually and sexually, as she breaks new ground and is able to achieve some insight as to why her first marriage failed. By the time she meets Ernest she is more self-aware, yet also more naive than one might expect from a hardened war correspondent approaching 40. She is not only seduced by Ernest’s physicality, but also by his fame and money and the promise of an easier life than the one she might live as a divorcée journalist. So she embarks on an unlikely second marriage.

The story of that marriage is filled with a myriad of detail: How she convinces herself that her duty is no longer to herself and to her work but to Ernest; how she becomes a “housewife” in Cuba, living in the house Martha Gellhorn bought so she and Ernest could get out of the tumult of Havana; how Finca Vigia and Ernest’s boat, Pilar, and his work become the three-pronged center of their lives.

Christian presents a vivid picture, plunging the reader into their daily life, the visits from friends and frenemies, Ernest’s work on The Old Man and the Sea and Mary’s assistance. Her most important contribution: suggesting that Santiago, the “old man,” live, and not die. We feel Mary’s claustrophobia when Ernest becomes cruel and abusive; we are privy to their sexual games, revel in their travels to Africa and Europe, wince watching Mary’s unbelievable patience when Ernest “falls in love” with an Italian woman young enough to be his grandchild.

We are also puzzled by the unraveling of circumstances around Ernest’s death. By then, because of the events in Cuba, Ernest and Mary had moved to Ketchum, in Idaho. There he was working on getting his early diaries of Paris — which he called A Moveable Feast — in shape for publication. But Ernest was failing mentally, as well as physically. They had gone to the Mayo Clinic where he had electroshock therapy, the treatment for severe mental illness at the time. Somehow, he convinces his doctors he is fit to go home, and then, when he is back, he finds the keys to the gun closet on the kitchen shelf where they are always kept. Toward dawn on July 2, 1961, just a few weeks short of his 62nd birthday, Ernest puts a gun in his mouth and shoots himself.

To save face, the news was that Ernest Hemingway died in an accident while he was cleaning a gun. No one believed it, although it would take years for the truth to come out. And, to his credit, Christian explores the reasons why Mary did not protect Ernest from himself, thus casting new light on their relationship.

Ernest and Mary Hemingway on safari in Africa, 1953-54. Photograph in the Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Because fame came so early to Ernest and his renown was given its second wind after he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1954, Hemingway’s life seemed very full and longer than it was, even though he died so young and so tragically. And because his fame has grown with the years (unlike Fitzgerald’s, which has diminished somewhat over time), it is easy to forget that there was still work to be completed, manuscripts to be gotten into the world, and the Hemingway legend to be protected and promulgated. Mary had her work cut out for her, and we see her doing it very competently for almost 20 years.

As readers of my earlier essay on Hemingway know, my husband and I actually went to Mary’s New York City apartment in 1978 when my first book of stories, Blood Relations, won honorable mention for the second PEN Hemingway Prize, which she had endowed as an annual prize for a previously unpublished writer. At that time Mary was at the top of her game, an eminent and celebrated hostess who had lots of people to court and be courted by. But she was not really all that interesting on her own, and by the early ’80s she began to descend into an inexorable alcoholism, dying of what the doctors called alcoholic dementia in 1986 at the age of 78.

Her demise was awful, and so was her legacy. Although there were small gifts to relatives and large bequests to the the Museum of Natural History, the United Negro College Fund and a small Black medical college, Mary did not adhere to Ernest’s wishes that she provide for his boys upon her death. By then, having garnered the royalties from the books and movies, she was a rich woman. Yet, Christian is blunt, “What was striking is that she left virtually nothing to Ernest’s sons.” Whether that was due to a mistake by Alfred Rice, Ernest’s lawyer, or to Mary’s choice to ignore Ernest’s wishes is not entirely clear, even after Christian did his own research into the matter. Whatever the case, she left anguish and resentment in the wake of her death.

So, although Christian ends his biography with a litany of her virtues, I was left with a bad taste in my mouth about this sometimes brave and compelling, yet often resentful and puzzling, woman. And a gut feeling that perhaps this last marriage, which seemed to break Ernest’s spirit, might have not been the very good thing that Mary’s biographer sincerely believes it was.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her latest novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Ernest Hemingway, Hemingway’s Widow, Mary Welsh Hemingway, Pegasus Books

Thank you, Ms. Silman, for such an outstanding review of this book which both piques my curiosity as well as deflating it for the dishonor that Mary committed — of virtually disinheriting Ernest’s sons from their rightful inheritance.

Vinca Figia????

The name of Hemingway’s Cuban home …it is now a museum. He lived there from mid-1939 to 1960.

It’s Finca Vigia but it’s just a typo as it’s typed correctly further down.

No self-styled “macho warrior nation” can afford to pass up a life and literature extolling the obsessive and over the top Hemingway manlitudeness however likely closeted the source.

Thanks for correction. It has been made.

RS

Thanks for your correction. It should be Finca Vigia. It is being made. Tiredness made me switch the first letters. Such is the life of a critic.

Roberta Silman

I have followed Hemingway’s travels from Paris to Havana to Ketchum.

His life was bigger than his stories.But , alas , it’s not Nick Adam’s that prevails but the old vulnerable fisherman.

I was a good friend of the Menocal and Arguelles families. I understand Mayito Menocal and Elicin Arguelles brought Hemingway to Havana. While Castro presented Hemingway as a sympathizer, little is known about the writer’s view of Castro.

Hemingway fits the super macho literary taste like a glove.

I went to Ketchum and read detailed accounts of Hemingway’s death. The gun was never found. There was no investigation. They were drinking and arguing, but everyone just believed Mary. One if Hem’s son suspected Mary of murder. Why has this never been looked into?

One thing I didn’t see in the article and very easily could have led to his suicide was that, Ernest had Hemochromatosis that went undiagnosed in his life. I have it too. One of the symptoms can be suicidal thoughts, but the real kicker is Liver Cancer when left untreated. His alcohol use only made this worse as alcohol helps the body absorb iron. Because his genetic disorder went undiagnosed, habits he developed along with the missed treatment were killing him.

Wow. I applaud your frankness. Having read “The Paris Wife,” and subsequent books on the Mrs Hemingway’s, I always felt that Mary was the coolest of the lot and clearly the most calculating. Her leaving access to the shotguns and ammo, while fully aware of the depth of Ernest’s depression, has long since left a sour taste in my mouth. But, disinheriting the sons? How perfectly dreadful & indefensible. I can only conclude that Mary allowed alcohol and score-settling to make decisions for her. Thank you for your candid views.

I visited the Hemingway home in Idaho last year. It was a privilege as well as moving experience as an author and writer myself.

Hemingway shot himself in the entrance way. His shotgun was ordered to be cut up and destroyed by Mary.

She did not want it to become a macabre relic/attraction as it surely would have.

She lived in the home for another 25 years. It is now as it was then – now a peaceful and beautiful reminder of days long past.

I’m a big fan of Hemmingway’s work as an author, but I also think that Hemmingway the man was quite a disgusting person in the absolutely disgusting way he treated his women.

I find it kind of rich how the author seems to blame the wife:

“But her ability to stand up for herself also brought out the worst in both of them”.

If only that shrew had just let him get his way there wouldnt have been this problem.

Mary and A. E. Hotchner conspired to trick Hemingway into entering the Mayo Clinic where he was electric shocked, 21 times in two separate stays there. The doctor who provided the initial diagnosis never even saw Hemingway, but made a diagnosis based on what Hotchner told him. The electric shock destroyed Hemingway’s memory and thus his ability to write. The main evidence of his alleged mental problem was that he insisted he was being followed and watched by the FBI. In fact, he was.

He didn’t attempt suicide until AFTER the electric shock.

Few people connect the fact that Hemingway was living in Cuba during the time of the Revolution, of which he was in full support, and the growing antagonism between the US and Cuba. The FBI surveillance and harassment increased in 1960 because of that.

For a more thorough discussion of Hemingway’s death and of his history as a stalwart anti-fascist and the FBI’s reaction, I’ve written a deeply researched account that can be read at https://www.necessarystorms.com/home/the-death-of-ernest-hemingway.

Fitzgerald’s reputation has diminished?? Why is The Great Gatsby the novel that is taught in high schools and English Lit courses across the country? Hemingway might be making a comeback but Fitzgerald still reigns.

Thanks for reminding me of Gatsby which is one of my favorite novels of all time. You are absolutely right but some of the fervent interest in his amazing stories and Tender is the Night and The Last Tycoon seems to be fading. Alas!

Roberta Silman

I’ve haven’t been able to open Gatsby since Andy Kaufman’s sketch in which he reads the first few pages out loud. I doubt that either Fitzgerald or Hemingway will be read much in another 25 years – although there will still be movies “based on” their more popular books – without the archaic prose that makes them “too hard” for readers born after 1970 or so. That is how popular culture – which made Hemingway more than Fitzgerald into a “major literary figure” despite the limitations of their work – functions. “Accessibility” trumps good writing.

Thank you, Roberta Silman, for calling my intention to this interesting book. However, that Mary Hemingway disinherited Ernest’s sons by his earlier marriage is hardly shocking news. It happens all too often among the celebrity widows and their step-children. For an illuminating look at these issues by estate attorneys, see https://www.hackardlaw.com/tony-curtis-estates-stepmothers-undue-influence/ and https://www.thinkadvisor.com/2019/03/27/what-the-nastiest-celebrity-estate-battles-can-teach-advisors/.

Anyway, I’m not sure what it is meant by “Ernest’s wishes that she provide for his boys upon her death.” How were these wishes manifested in a legal document? It all sounds very much like the opening situation in Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility.” Did Hemingway make earlier financial provisions for his children, such as a trust fund? Were the sons mentioned at all as heirs in his will? Was an original will changed in Mary’s favor not long before his death? For that matter, did Ernest have a will at all? I’ll have to read the book to find out, I guess.

First of all, thank you, Roberta, for an interesting review. I am engaged in a Hemingway project at the moment (though not one those who worship at the shrine of Hemingway might like) and I am always on the look-out for more facts, details and books. Because of your review (you seem to like Timothy Christian’s book) I shall probably read it, although it might be only peripheral to my undertaking.

As for that undertaking — and encouraged by fellow commentators Shirley Freitas and Sue Grossman who have also left a web link — might I draw your and others’ attention to my project? That is primarily so that I might get feedback with a view to correcting any howlers and possibly improving what I present.

The ‘front page’ of the project (called The Hemingway Enigma: how did a middling writer achieve such global literary fame) is here https://hemingway-pfg.blogspot.com/p/the-hemingway-enigma-preface.html

Thank you.

My name is Ron Hauser an International Aclaimed Artist and a member of the Hemingway Society . Had my Hemingway Art and Speaking invitation to the 19th biannual Hemingway conference and Sheridan Wyoming and cook City Montana July 2022. I invite you to go to my website at ronhauserartist.com and see my latest work and listing of a Hemingway Speaking engagement in April 13th! Had a wonderful meeting and exchange with Valerie Hemingway who added an awful lot to the Mary Walsh story about her and Hemingway’s wife and what happened after his death but Mary called her and had her meet in Cuba with special Arrangements together of all his manuscripts anything they could find in his Cuba home and transported back to ketchup Idaho where they together work furiously to pull together different unfinished works and create new ones Etc! She wrote a great book called Running to the Bulls. He is married Hemingway’s youngest son Gregory well that’s the story all through itself. Would enjoy communicating in the future and loved your work I too have had a strange feeling about Mary Walsh Hemingway and their relationship and how things ended. Hemingways children his three boys and grandchildren should have no way then cut out to enrich Mary’s life and Legacy. That’s just my opinion but maybe maybe not such a strange one. Thanks again for your work and I love reading what you had to say.