Jazz Review and Appreciation: Wadada Leo Smith’s “The Chicago Symphonies”

By Steve Elman

If you are not familiar with Wadada Leo Smith as an artist or as a thinker, you could start with The Chicago Symphonies and know that you are engaging with some of his finest work.

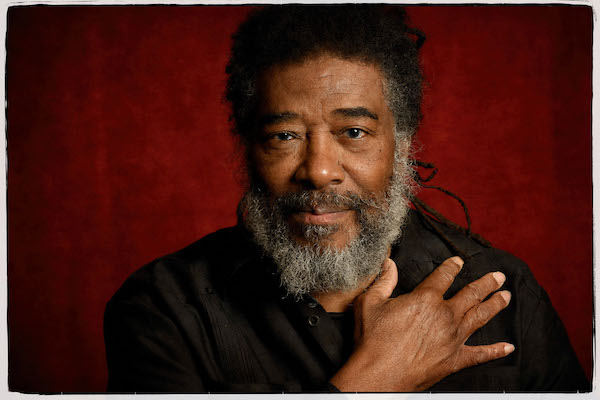

Wadada Leo Smith — his smile is in almost everything he does. Photo: Dominik Huber

The Present is always conversing with the Past about the Future.

Almost every work of art grapples with this notion in one way or another, but few take it on explicitly. Wadada Leo Smith’s Chicago Symphonies is one of those few.

Smith builds this monument brick by brick, movement by movement, honoring great figures of Midwest America — for the most part avant-garde jazz people of his native Chicago.

It is another skyscraper for the city where the skyscraper was invented.

In the history of art, Chicago has been playing second fiddle for a long time. Everyone knows that the aesthetic world (at least the American one) turns on New York City’s axis. Just look at Wikipedia’s list of songs about New York.

Even in the rarefied world of avant-garde jazz and improvisational music, the giants put their flags in the ground in New York, right? Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman (yes, yes, I know, born and bred in Texas) … As Gordon Jenkins wrote in “New York’s My Home,” sung so memorably by Ray Charles, “When you leave New York, you ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

And yet.

In what city did the Big Thinkers of the avant-garde shape the music they sent out to the wider world? Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Wadada Leo Smith… It’s Chicago, “that toddlin’ town,” as Fred Fisher put it in his anthem made famous by Frank Sinatra.

But there’s more: With the benefit of hindsight, we can now see that Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (AACM), spearheaded by Abrams and sparked by Joseph Jarman and other senior members of the Chicago musical elite, can claim to be the world’s most important finishing school and proving ground for improvisational individuality. Mitchell, Braxton, Threadgill, Smith, Jarman, Lester Bowie, Leroy Jenkins, Amina Claudine Myers, George Lewis, Chico Freeman, Douglas Ewart, Nicole Mitchell … the past and present roster demonstrates that association with AACM does not foster or signify a “school” of thinking or playing. Instead, it is about an openness to the world of sound, and harnessing that openness in service to profundity.

But perhaps there is one thing that marks AACM artists as different from those annealed in the New York furnace: their use of space. Where Coltrane and Taylor engulfed their listeners in flurries and furies of notes, and where, even today, the mark of how good you are is how fast and clean you play, the Chicagoans love air; they listen, and play (sometimes a lot), and listen some more, and play some more. It’s no wonder that Air was the name of Henry Threadgill’s cooperative trio with Steve McCall and Fred Hopkins.

And no one among the Chicagoans listens more carefully or plays with greater sensitivity to those around him than Wadada Leo Smith, who celebrated his 80th birthday in December. That occasion gave the Finnish label TUM the opportunity to bring to market a gift basket of releases that isn’t full yet (see More below) — with more due in the months to come.

Smith is perhaps the most openhearted of the Chicago Thinkers. All of them, as personalities, are charismatic and generous, but their music can be daunting. Roscoe Mitchell’s is austere and deeply intellectual. Anthony Braxton’s is so vast in its ambition that it is almost beyond category. Henry Threadgill’s is relentless in its personal seeking and sphinx-like in its titling.

But Smith’s smile is in almost everything he does. Generous homage to his predecessors and peers appears frequently in his work. His willingness to meet anyone on their home turf has made his list of collaborators one of the most wide-ranging in music. And his solos are always straight from the heart.

Even in his earliest recordings — on Braxton’s Three Compositions of the New Jazz (Delmark, 1968) and on two LPs from a 1970 live performance by the Creative Construction Company (CCC and CCC, Vol II, both on Muse, 1975 and 1976) — Smith stands out from his AACM companions with solos that seem to come from a peaceful place, even if all around him is a swirl of little instruments and roiling percussion.

The process of hearing Smith’s music (then and now) should not be taken lightly. An artist who seeks so earnestly to communicate deserves full, undivided attention when you listen. You should give him more than one listen before you come to a conclusion about what you’ve heard. This is a call to swim against the tide at a time when even art music has become an accompaniment to some other activity, but if you take the time to clear your schedule, turn off your phone, close your eyes, and listen hard, you will be rewarded.

And in the case of The Chicago Symphonies, released late last year on TUM, your reward may be a little healing for your soul in a time of trouble. If you are not familiar with Smith as an artist or as a thinker, you could start here and know that you are engaging with some of Smith at his finest.

The context:

The two recording sessions represented in The Chicago Symphonies come from 2015 and 2018, before the onset of The Dark Ages, when Smith and his companions may have been reflecting on the zeitgeist of a corner turned. The first three of these CDs are a genuine triptych, a kind of past-present-future trilogy, with individual movements dedicated to Chicago masters, mostly from the AACM school. The fourth is a celebration of idealism and turning points in American history, dedicated to Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama.

The two recording sessions represented in The Chicago Symphonies come from 2015 and 2018, before the onset of The Dark Ages, when Smith and his companions may have been reflecting on the zeitgeist of a corner turned. The first three of these CDs are a genuine triptych, a kind of past-present-future trilogy, with individual movements dedicated to Chicago masters, mostly from the AACM school. The fourth is a celebration of idealism and turning points in American history, dedicated to Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama.

For the first-time listener, it may be important to note that these are symphonies as Wadada Leo Smith defines them — not as pieces for orchestra, but as multimovement works for jazz quartet, the ensemble that Smith calls his “Great Lakes Quartet.”

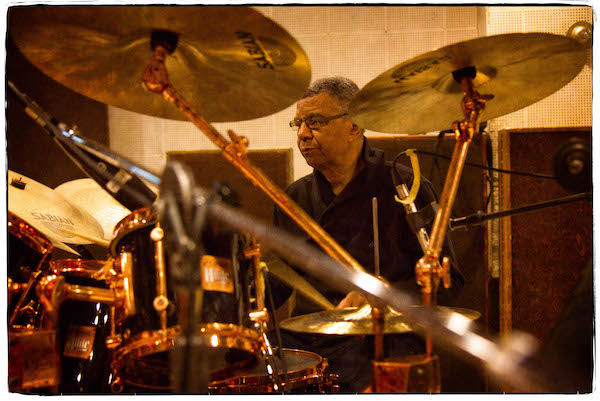

The foundation of the group is a rhythm section of mighty ability. John Lindberg (who’s a couple of weeks from his 63rd birthday at this writing) is one of the world’s great virtuosi on his instrument. Smith must prize his perfect intonation, his impeccable bowing technique, and his ability to listen. Drummer Jack DeJohnette (who’ll turn 80 this year) requires no such encomia. He’s just the best drummer alive today.

The saxophone / flute chair belongs to Henry Threadgill (who turned 79 on February 15). He first occupied it when this group recorded Smith’s The Great Lakes Suites in 2014. He and Smith are among the four Big Thinkers associated with Chicago, and his willingness to work alongside Smith, contributing to the leader’s music but never trying to upstage him, is a mark of the respect the two have for one another. Every solo he contributes on the first three discs is forceful and thoughtful at the same time, and completely within Smith’s design.

Filling the reed chair in the fourth CD (The Sapphire Symphony) is Jonathon Haffner (who turns 45 this year). If he is less prominent there than Threadgill is in the first three discs, it may be appropriate for an individual personality to be subordinate to the grandness of the fourth disc’s ambition. He takes two significant solos, both on alto; his solo in the fourth movement (“Barack Hussein Obama at Selma: The Bridge of Transformation”) is particularly good, picking up the end note of Smith’s solo and moving gradually away from it in circles, with a spare, vocal approach.

The artist as artist:

Wadada Leo Smith, like Braxton and Threadgill, has invented an unconventional notation system for his pieces. He calls it his “ankhrasmation,” and he trains the musicians he works with to read and interpret the scores he paints / writes. (These scores are art works in themselves. To see some of them and read Smith’s guide to playing them, take a look at these pages of his site where he discusses his Four Symphonies named for the seasons.)

This does not mean that the music that results is formless or abstract. In fact, much of the “written” material as it finally emerges could be notated conventionally with some creative license. But Smith would surely say that any notated version could not represent a definitive version of the music. His way of thinking offers great freedom to the player within a set of structures, and those structures do not rigidly dictate the realized form of each performance.

In this release, as in nearly all of his work, Smith’s Present is conversing with his Past. His solo work has always drawn on great traditions, especially the work of Miles Davis, and that influence is here again. For example, in both the fourth movement of The Diamond Symphony and the opening movement of The Sapphire Symphony, there is a clarion call in the trumpet that echoes Miles’s climaxes in Wayne Shorter’s “Sanctuary.”

The music and messages of The Chicago Symphonies:

Most of the movements follow a traditional pattern in music — theme, variations, theme — which gives the listener something of a guide to the way it unfolds. The variations are sometimes like traditional jazz, where they take the form of solos from one or more featured players. But there is a lot of variation. Sometimes the solos segue into duets. Sometimes the group improvises collectively (but thoughtfully). Sometimes Lindberg or DeJohnette disappear, changing the color of the music. And in nearly every case, the music is not structured with a comfortable harmonic center or a set of repeating figures to ground the solos.

This is just one of the reasons you must listen carefully. If you try to hear this music as an accompaniment to some other activity, you will lose its threads.

However, there are several notable exceptions where harmonic foundations are established, and each of those exceptions adds dramatic force to the symphony in which it appears.

Jack DeJohnette. Photo: Dominik Huber

An example:

The fourth movement of The Gold Symphony is titled “Creative Music: West End Blues and the Sonic Weather Bird; Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Lil Hardin and Baby Dodds.” It is an affectionate tribute to a group of pioneers who changed the world of music with their achievements in Chicago in the late ’20s. Like nearly all of the tributes here, this one does not suggest the style or stylist it honors, but reflects the composer’s feelings about the subjects.

The first section (and the reference to King Oliver’s “West End Blues” in the title) may be a free-form nod to one of the most famous moments in jazz history — a solo trumpet introduction by Armstrong of such brilliance that it still sounds great 94 years later. Smith does not begin the movement solo, as you might expect. Instead, the music begins as a conversational duet between trumpet and drums, with DeJohnette very active all over his kit. Then there is a unison theme from the horns and bass in short one- or two-note bursts. Threadgill follows with an open-harmony solo over slippery bass and spacey percussion.

Smith’s solo has even more active bass and drum support. It’s similar to what he plays in the opening duet, also declamatory, with more smears and some multiphonics. He comes to a definite end, and the music stops for a breath-pause.

Then the horns have a brief fanfare, which sets up a loose ostinato from bassist John Lindberg (the harmonic foundation I referred to above). Smith takes a second solo on this foundation; it gradually opens into a free-form conversation with the bass and drums, anchored by occasional hints from Lindberg at the ostinato. The result is an exuberant display of the iconoclastic Armstrong spirit, with a hint of an elegy just behind the smile.

Then the group moves harmonically and rhythmically away from the ostinato into a kind of “free bridge.” Lindberg and DeJohnette bring the energy down, and the two horns have six notes in conclusion.

Each movement in the four-CD set has a sense of roundness and completeness, and represents a full statement in itself. But the cumulative impact of the various movements is greater than the sum of its parts. In that sense, these are genuine symphonies, even though there is no orchestra.

The titles of the individual movements provide clues to the overall direction of each symphony. For your help in approaching the music, let me oversimplify and suggest the overarching themes.

As I noted above, the first three discs can be seen as a triptych — very approximately corresponding to past, present, and future.

The first disc, The Gold Symphony, has five movements, each remembering what might be called great personalities of Chicago music — Amina Claudine Myers, who is still very much with us; the Art Ensemble of Chicago; the early personnel of Joseph Jarman’s group (which contained two much-mourned players who died very young, Charles Clark and Christopher Gaddy); Armstrong and his Chicago colleagues; and the late John S. Jackson, the first secretary of the AACM.

The second disc, The Diamond Symphony, has four movements. Its overall theme might be summarized as “the past as foundation for the present.” It is bookended with movements that honor two of the musicians playing them — the first commemorating Threadgill’s cooperative trio Air and the last pointing to DeJohnette’s Special Edition bands. In between, the second is titled “Profile of the Next Generations,” and the third honors the great father-figure of the AACM, pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, who passed away after the movement was recorded.

The third disc, The Pearl Symphony, has five movements. Although three of the musicians honored here are gone — violinist Leroy Jenkins, visionary bandleader Sun Ra, and Kelan Phil Cohran (onetime Ra trumpeter and founder of a family dynasty of musicians in Chicago) — the music world has yet to appreciate fully their contributions and build on their achievements. The bookends in this symphony name living artists who similarly are still “deserving of wider recognition” — Anthony Braxton and Smith himself.

John Lindberg, Henry Threadgill, Wadada Leo Smith, Petri Haussila, Jack DeJohnette and the late Muhal Richard Abrams. Photo: Dominik Huber.

The last of the four, The Sapphire Symphony, stands apart from the other three, thematically and structurally, and it calls for a more detailed discussion.

It is a set of five movements, with a mirror format in the titles and in the music itself:

“Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States of America”

“Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg; Two Seven Two, 1863”

“The Visionaries, Abraham Lincoln and Barack Hussein Obama”

“Barack Hussein Obama at Selma: The Bridge of Transformation”

“Barack Hussein Obama, the 44th President of the United States of America”

Is the music “political”? That depends on how you define politics. It certainly represents people and events that are very important for Wadada Leo Smith.

The first movement has a martial / commemorative feel, with the suggestion of a slow cortege in the bass. Smith’s music over this foundation is perhaps a call to arms as well as a cry of anguish for the assassinated Lincoln.

The second and fourth movements commemorate two great speeches that marked pivot points in American history. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (11/19/1893), 272 words long, honored the Union dead in the battle that is now seen as the turning point in the Civil War. Obama’s 50th-Anniversary-of-Bloody-Sunday Address (3/7/2015) honored those who were injured and hospitalized — including the late John Lewis — in the 1965 march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which is now seen as the event that ensured the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Both speeches are reprinted in full in the CD’s booklet, and Smith clearly intends the listener to read them and think about them. Both speeches use similar language to remember the struggles and define those moments for the future. Lincoln: “The world … can never forget what they did here.” Obama: “What they did here will reverberate through the ages.”

Both of these movements use repeating foundations which make them immediately communicative — a repeating chord structure in the second, and a bass ostinato in the fourth. In each, there is a Smith trumpet solo of extraordinary power and beauty — muted in the second and open in the fourth.

Between these two is the third movement, the only one dedicated to both presidents. It is framed by a long-breathed theme, with yet another great Smith solo at the center — he begins muted, but in the next few minutes, he removes and replaces the mute several times to change the timbre of his notes, and concludes with open horn, leading to a powerful dialogue with drummer DeJohnette and a brief ostinato passage anchored by Lindberg.

The last movement rounds the vision. Mirroring the first movement, it is a summing-up of a presidential legacy, but the tone here is very different from that of the first. This is no elegy; the music reflects both Obama’s passion and the composer’s respect for him.

How is this a “Chicago symphony”? It is and it isn’t.

It’s something of a stretch to connect Lincoln to Chicago, but as an Illinois attorney and then politician, he could not avoid the Midwest’s central city, and he is “present” in the city today in some six memorial statues. Perhaps his most notable visit came in 1860, when he had a life mask taken that inspired Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s statue that stands in Lincoln Park today.

Henry Threadgill & Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: Dominik Huber

But Barack Obama and Chicago are inextricably linked. He moved there in 1985 to study law, which led to teaching, and then the beginning of his political career as a state senator. He considers the city his home, and his Presidential Center will eventually be there, on the South Side.

So, as a summary to the cycle of four symphonies, this one is tied to the Windy City but soars high above it like a drone to observe the nation as a whole.

Does this great vision have a blind spot? Well, nothing is perfect.

Smith might have honored more Midwestern women. Only two are specifically mentioned in movement titles — pianist Lil Hardin and singer Sherry Scott. What about classical composer Florence Price, active in Chicago for 25 years? Or Dinah Washington and Sheila Jordan, both rooted in Detroit? Or Betty Carter, born in Flint, MI? Or Michelle Robinson Obama?

Not that these omissions make The Chicago Symphonies less great, but they are reminders that all of us need to pay more attention to the women of the past if we are going to hear what needs to be said about the future.

Today, Wadada Leo Smith makes his home in New Haven. Physically, he’s not far from New York City. Spiritually, he’s still Chicago to his core.

And The Chicago Symphonies is a can-do testament, as optimistic and celebratory as the poetry of Carl Sandburg, as forceful as the novels of Upton Sinclair, as lyrical as the work of Willa Cather, saying (among other things), “Look what we can do when we work together.” It is a document of a hopeful time, a reminder that better angels have guided us before and may yet guide us still.

More:

I look forward to revisiting Smith’s work later this year, after I’ve had the chance to digest and consider his upcoming seven-CD set of 12 string quartets. This set will be a landmark, the first substantial recording of pieces for string quartet ever written by a composer associated with jazz. It is due for release on May 20, 2022.

These pieces will not be traditionally classical, of course. The music is played by the RedKoral Quartet — Shalini Vijayan, violin, a member of the Lyris Quartet; Mona Tian, violin, a member of LA-based new music group WildUp; Andrew McIntosh, viola, a solo artist and composer in his own right; and Ashley Walters, cello, one of Smith’s frequent collaborators. There will be guest artists as well — Pulitzer Prize-winning composer-pianist Anthony Davis; LA-based harpist Alison Bjorkedal; baritone Thomas Buckner, a former member of AACM who has worked with a number of AACM heavyweights; and Smith himself.

Smith discusses them in a recent interview with Rob Shepherd at Post Genre: “These string quartet pieces are something I’ve been working on for almost fifty-seven years now…. As of now, I have composed fifteen string quartet pieces…. I consider the [first] twelve coming out to be a landmark achievement for me. They show fifty-some-odd years of music activity, which I think is rare … in music.” And on his website, Smith says, “The twelve string quartets … [were initially inspired by] Ornette Coleman’s recording of ‘Dedication to Poets and Writers.’… The scores are essentially non-metric, and a full page represents a complete ‘bar’ length, with no maintaining of the concept of downbeat and upbeat idea. The ensemble’s leadership articulation continuously fluctuates from person to person as the decision for continuity keeps changing from page to page.”

TUM’s year-long festival of Wadada Leo Smith releases began in March 2021 in Finland. The recordings began to appear internationally in May. The string quartets and a set of percussion duets will be the last in the series.

TUM’s year-long festival of Wadada Leo Smith releases began in March 2021 in Finland. The recordings began to appear internationally in May. The string quartets and a set of percussion duets will be the last in the series.

Each one of these six TUM releases is tantalizing, and each is a bit of a commitment. You have to find the time to listen, as I’ve noted above, and you have to have your ears tuned to the particular instrumentation of each one, since they are all sonically distinctive. But what a feast of art awaits you.

— Trumpet (TUM, international release in May 2021; recorded July 2016): A 3-CD set of solo trumpet composition / performances.

— Sacred Ceremonies (TUM, international release in May 2021; recorded 2015 and 2016): A 3-CD set with three different acoustic experiences — a CD of Smith duets with the late Milford Graves, one of the most musical of avant-garde drummers; a CD of Smith duets with Bill Laswell, who can make his electric bass sound like a funk machine, a melodious guitar, or an interstellar signal; and a CD where the three of them work together.

— A Love Sonnet to Billie Holiday (TUM, international release in November 2021; recorded November 2016): This single CD brings Smith together with pianist Vijay Iyer and drummer Jack DeJohnette. It includes three compositions by Smith, one by Iyer (which includes an excerpt from a speech by Malcolm X), and one by DeJohnette. My colleague Steve Feeney has written informatively about it in this review.

— The Chicago Symphonies (TUM, international release in November 2021; recorded March 2015 and June 2018): discussed in this post.

— String Quartets 1 – 12 (TUM, international release scheduled for May 2022): previewed above.

— Emerald Duets (TUM, international release scheduled for May 2022): A 4-CD set of one-on-one encounters with four master percussionists — Pheeroan akLaff, Han Bennink, Andrew Cyrille, and (once again) Jack DeJohnette.

My colleague Michael Ullman has written extensively (and so beautifully) about Smith in the Fuse that I struggled to say something here that he has not already said more eloquently.

He offered superbly informed introductions to six earlier releases by Smith. Here are links to all of them:

- The Great Lakes Suites (TUM, 2014) – This is the set that introduced the group performing on The Chicago Symphonies.

- a cosmic rhythm with each stroke (ECM, 2016)

- Najwa (TUM, 2017) and Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk (TUM, 2017)

- To Be Surrounded by Beautiful, Curious, Breathing, Laughing Flesh Is Enough (Bandcamp digital release, 2020)

BTW, I also heartily recommend Michael Ullman’s recent review of Cecil Taylor: The Complete Legendary, Live Return Concert (Oblivion, 2021)

![]() Finally, a word about TUM. Each of this nonprofit Finnish record label’s CD packages is a model of aesthetic elegance, with cover art by Finnish artists, extensive notes by the musicians, and beautiful photography. The label has shown remarkable commitment to artists on the cutting edge. In addition to many releases by Wadada Leo Smith, TUM has issued sets featuring Barry Altschul, Billy Bang, Andrew Cyrille, Joe Fonda, Jon Irbagon, Oliver Lake, Bill Laswell, Louis Moholo-Moholo, William Parker, Enrico Rava, and preeminent Finnish jazz musicians including Juhani Aaltonen, Henrik Otto Donner, and Heikki Sarmanto.

Finally, a word about TUM. Each of this nonprofit Finnish record label’s CD packages is a model of aesthetic elegance, with cover art by Finnish artists, extensive notes by the musicians, and beautiful photography. The label has shown remarkable commitment to artists on the cutting edge. In addition to many releases by Wadada Leo Smith, TUM has issued sets featuring Barry Altschul, Billy Bang, Andrew Cyrille, Joe Fonda, Jon Irbagon, Oliver Lake, Bill Laswell, Louis Moholo-Moholo, William Parker, Enrico Rava, and preeminent Finnish jazz musicians including Juhani Aaltonen, Henrik Otto Donner, and Heikki Sarmanto.

The ownership, management, and direction of the label are almost invisible; ego does not seem to be driving any aspect of the label’s business philosophy. Founder Petri Haussila’s name rarely appears with any prominence on the label’s product. He credits himself (in tiny print) with some of the liner notes on The Chicago Symphonies, and he tucks his “producer” credit into a caption of a photo where he appears behind Smith, Threadgill, DeJohnette, Lindberg and Muhal Richard Abrams. In fact, the “Executive Producer” credit, so ubiquitous throughout the recording industry, appears on none of the TUM releases I own — and I have one of the first ones, the gorgeous collaboration of Juhani Aaltonen and Henrik Otto Donner called Strings Revisited (2003). Take a bow, Petri. Your work deserves at least a brief moment for you in the spotlight.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Fine in depth examination and analysis of an artist whose command has expanded broadly, and whose beautiful earlier music – Spirit a chaser is one favorite, You, Miles! Another – still thrills. Thanks for this article.