Album Review: Deerhoof and Wadada Leo Smith — Electrical Soul Music

By Michael Ullman

That this assemblage works so well is a tribute to the big ears and hearts — and collective intelligence — of all the players here.

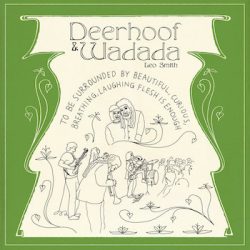

To Be Surrounded by Beautiful, Curious, Breathing, Laughing Flesh is Enough , Deerhoof with Wadada Leo Smith.(Bandcamp exclusive: all proceeds to benefit Black Lives Matter)

Satomi Matsuzaki and Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: courtesy of the artists.

The title of Deerhoof’s collaboration with trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, who has been an adventurer in new music since the late ’60s, comes from Walt Whitman’s I Sing the Body Electric. In the poem, Whitman daringly celebrates (in detail) the bodies of men and women, seeking to “discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of soul.” It’s a goal many musicians must share, though they would express themselves more circumspectly.

Whitman’s electrical soul no doubt contains flickers of humor, a specialty of the quartet Deerhoof, which now consists of singer-bassist Satomi Matsuzaki, dueling guitarists Ed Rodriguez and John Dieterich, and drummer Greg Saunier. The group has taken various forms since the ’90s. The musicians are not as sublimely confident as Whitman; few people are. Some of the brusque lyrics on their new album are repeated over and over: “You can outlive your executioners” and “Stay alive, see if you can stay alive.” Singer Matsuzaki, as if to fend off the occasional bleakness, ends up chanting “la, la, la.”

Deerhoof’s music is nothing if not dramatic. This live concert recording begins with a thumping drum rhythm. Equally aggressive guitars enter via a series of riffs that, though not particularly innovative, are still effective. Minimal lyrics are introduced: “”Obsession/ You’re reading my mind/ How sad.” The second chorus sounds something like “Paranoia boogie oogie.” The vocals sometimes take a semi-spoken form, uttered in Matsuzaki’s clear, appealing, Alice-in-Wonderland voice. Her messages are occasionally depressing, but there is a jokiness as well. For example, “Chandelier Searchlight” begins with Saunier striking the tom-tom, waiting, stopping and, after a pause, continuing this stop-and-go-pattern. There’s more silence here than sound; guitarist and bassist attempt to match his stuttering sonic strokes. The melody that follows is predictably insouciant.

Of course, this hard core jazz fan was waiting for the entrance of Wadada Leo Smith, who joins Deerhoof on the last five numbers. It isn’t a pairing I would have dreamed of. In his notes for the album, Wadada argues that democracy has not yet been achieved anywhere — except (perhaps) on the bandstand. Saunier notes the risk of playing with the trumpeter, but calls this kind of collaboration a way out of the corporate trap: “That’s why I’m touched that a master improviser like Wadada would bring up true democracy. To me, democracy and improvisation are linked, and they appear spontaneously at times like these, when strangers come together to take action, and there is no rulebook.”

Wadada sounds all in. He joins the band on “Snoopy Waves.” He waits, listening until a groove is established, then inserts a single note. After a pause, he becomes part of a vigorous conversation. Finally, he signals an ending: a slowed down, gradual conclusion in which Wadada gives himself the last word. He’s there from the beginning of “Breakup Songs,” filling in the gaps among the vocal lines with bright scales and patterns, coming off like a 21st-century Louis Armstrong. Initially, the vocal seems to lament the end of a relationship, albeit from an emotional distance. Then the sound thins out, the bass plays a monotone pattern overlaid by intermittently frantic lines by the guitars and, via comic deadpan, the singer’s final bored word arrives: “Anyway.” She’s already over it.

Wadada sounds all in. He joins the band on “Snoopy Waves.” He waits, listening until a groove is established, then inserts a single note. After a pause, he becomes part of a vigorous conversation. Finally, he signals an ending: a slowed down, gradual conclusion in which Wadada gives himself the last word. He’s there from the beginning of “Breakup Songs,” filling in the gaps among the vocal lines with bright scales and patterns, coming off like a 21st-century Louis Armstrong. Initially, the vocal seems to lament the end of a relationship, albeit from an emotional distance. Then the sound thins out, the bass plays a monotone pattern overlaid by intermittently frantic lines by the guitars and, via comic deadpan, the singer’s final bored word arrives: “Anyway.” She’s already over it.

On “Mirror Monster,” Wadada plays beautifully lyrical lines over the trilling of the guitars until the bass arrives and contributes some funk. Eventually, the tune evolves into a duet between vocalist and trumpet, with Smith echoing Matsuzaki’s lines until his final phrase. Wadada sounds very much at home, whether he’s adding to the cacophony or asserting his own idiosyncratic lyricism. That this assemblage works so well is a tribute to the big ears and hearts — and collective intelligence — of all the players here.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

.

Tagged: Breathing, Curious, Deerhoof, Laughing Flesh is Enough, Satomi Matsuzaki, To Be Surrounded by Beautiful