Book Review: “The Sentences That Create Us” — In Prison, Triumphs Great and Small

By Bill Littlefield

It’s no exaggeration to say that some of the men and women who embraced writing while they were in prison and whose work is featured in this book were writing for their lives.

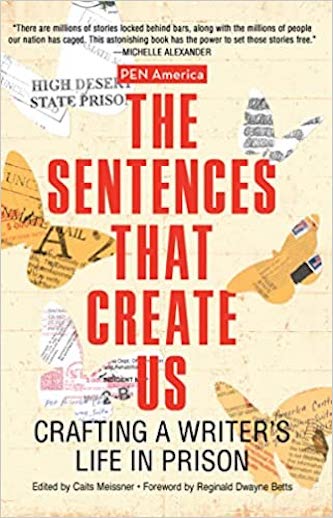

The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting A Writer’s Life In Prison, by PEN America. Edited by Caits Meissner. Forward by Reginald Dwayne Betts. Haymarket Books, 325 pages, $24.95 (paper).

In one of the introductory sections of The Sentences That Create Us, Susan Rosenberg, who served 16 years in federal prisons before being granted clemency in 2001, writes that “the struggle to create inside of a living death is an enormously difficult and at times dangerous endeavor.”

In one of the introductory sections of The Sentences That Create Us, Susan Rosenberg, who served 16 years in federal prisons before being granted clemency in 2001, writes that “the struggle to create inside of a living death is an enormously difficult and at times dangerous endeavor.”

Ms. Rosenberg, now an adjunct lecturer at Hunter College, bases this assertion on what she and various incarcerated men and women have discovered about the best way to survive while they are locked up. They do not create, and if they struggle, they try to do it quietly. They learn to keep their heads down and keep their feelings to themselves. Demonstrating vulnerability is way past dangerous. One woman who’s learned that lesson acknowledges in her writing that she doesn’t let herself cry unless she’s alone. Finding some place to be alone while incarcerated is a challenge, unless you’re already locked in solitary.

But Ms. Rosenberg’s contention is that learning to write while incarcerated requires the acknowledgement of vulnerability. That’s one of the tenets of The Sentences That Create Us. Students in writing workshop classes make progress by sharing what they’re thinking and what they’re feeling. The risk is evident. As one former student in a prison writing workshop puts it, “There are two practical concerns that arise while writing truthfully: protecting yourself, if incarcerated, and protecting other people.” But the benefit of “writing truthfully” can be extraordinary. As Sterling Cunio, who spent 26 years in prison, beginning when he was 16, writes: “The ability to resist silencing is one of the greatest freedoms writing can empower.” It’s no exaggeration to say that some of the men and women who embraced writing while they were in prison and whose work is featured in this book were writing for their lives.

A lot of the advice evident in this book is meant specifically for incarcerated writers. As former inmate Mitchell S. Jackson, now a social justice advocate, writes: “There’s beautiful benefits, especially when you’re locked down, to disremembering, much profit in focusing on what’s to come.” That advice notwithstanding, many of the writers featured in The Sentences That Create Us focus on the prisons where they live and the system that has created and sustained those prisons and filled them with so many people that more prisons have been built to hold the overflow. Writing and sharing that writing can be a powerful weapon against those who prefer to keep the incarcerated silent, invisible, and alone.

But a lot of what the writers represented in this book profess seems to me potentially useful to anybody trying to write. One of my favorite examples comes from Curtis Dawkins, who was sentenced to life without parole in 2005. He’s the author of a collection of stories, The Graybar Hotel, published by Scribner in 2018, and he’s an advocate of hunkering down to the task of composition without excuses. He writes: “There is no such thing as writer’s block. There is only ‘fear of writing badly’ masquerading as something that sounds official.” Feels like something creative writing professors at even the elite universities might want to tell students who haven’t been getting in their work on time.

The workshop or writing circle is paramount for a lot of the writers who contributed ideas and exercises to The Sentences That Create Us. As Spoon Jackson puts it, “collaboration has become my food.” Like numbers of his fellow contributors, Jackson has made a life and a living out of writing. It’s no surprise that in telling their stories, some of those contributors emphasize their desire to be published. The imperative to get the word out about their circumstances is powerful for men and women driven by rage at the system that has tried to break them. But more powerful in the narratives that make up the book are the stories of personal change. One jailhouse lawyer was surprised at the extent the writing class helped him in a struggle more significant than getting the words right: the struggle to get out. “Lo and behold,” writes Alejo Rodriguez, “once I began writing my own appeals, and doing so in my own voice, I started to win some – and for others as well.” Mr. Rodriguez currently teaches at Columbia Law School.

The Sentences That Create Us should be an obvious choice for incarcerated men and women who need convincing with regard to the benefits of a writing course, or who have already begun to understand themselves as writers. That understanding can require a leap, but it’s a leap students in workshops haven’t had to make alone. Derek Trumbo, a winner of multiple PEN Prison Writing Awards, perhaps speaks for many of his former classmates when he writes: “Only somewhere along the way, I’d become convinced I wasn’t smart, educated, or articulate enough to say anything someone else would ever give a damn to hear.” To write one’s way out of a hole like that must have been at least as exhilarating as it was difficult.

The people who teach writing courses in prisons will also benefit from the exercises, suggestions, and strategies for doing powerful and subversive work under difficult and frustrating circumstances. But the book is also significant for the glimpse it provides into the lives of various incarcerated people and the evidence of their imaginations, their determination, and their triumphs, great and small.

Bill Littlefield works as a teaching assistant at MCI-Concord with the Emerson Prison Initiative.