Arts Remembrance: Film Critic Michael Wilmington — A Memory

By Gerald Peary

Remembering film critic Michael Wilmington, a unique guy, and friend, whom I knew for 53 years.

Michael Wilmington, 75, who died in Los Angeles on January 6 of complications from Parkinson’s Disease, was an esteemed longtime film critic for the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and other publications. But, as he told me, he was fired from his first job reviewing movies as a teenager in Williams Bay, WI, because the newspaper balked at Michael writing an occasional negative review. Michael’s editor was afraid of losing advertising.

When Michael arrived in Madison in the mid-1960s, he made his mark first at the University of Wisconsin as a maniacally intense, Method-influenced stage actor. I saw him in a series of university productions, and I was most impressed. Around 1967, I was directing an off-campus production of Peter Pan, and I approached Michael on the streets of Madison and offered him the role of Captain Hook. Our first meeting. Michael looked at me suspiciously and said “No” to being directed by an unknown.

I would like to say that our encounters in Madison got more pleasant, but that was not the case. Michael and I were both part of an astonishingly passionate and extremely contentious film scene at Wisconsin, where, around 1970, certainly more 16mm film societies existed than on any other campus in America. This was during the Vietnam War, and the film lovers broke into two groups, the “politicos” (I and others), who wanted left-wing and agitprop cinema, and the “aesthetes” (Michael and others), who opted for personal, formally elegant films regardless of their politics. My how these two groups fought! Even literally: it’s too silly today to explain the circumstances which led to Michael leaping on my back one day in the Wisconsin student union and wrestling me to the ground. Luckily, my girlfriend at the time pulled Michael off me, two against one, and no punches were thrown.

By the late ’60s in Madison, Michael had taken to writing film criticism. He was from the first incredibly brilliant, but — he certainly got over this habit in his professional heyday — impossible at making deadlines. When I was the arts editor for the Daily Cardinal, the campus newspaper, Michael was only my fourth-string film critic. As superb as he was, I could never count on him to get his reviews in on time. More arguments between us: it took him endless months to edit the text that was our big scoop: together, we’d managed the only interview in many years with Warren Beatty, when the Bonnie and Clyde star came to Madison for the George McGovern presidential campaign.

At the end of our chat, as we were walking out the door, Beatty smiled at us and said, “When you boys are in L.A., look me up.” Neither of us ever did.

I wasn’t the only one who found Michael the most challenging collaborator. He teamed with another intellectually precocious Madisonian, Joseph McBride, on a book on their favorite American filmmaker. They fought incessantly. I felt at times that they could have murdered each other, but these two geniuses in their 20s turned out an abiding masterpiece of film studies: John Ford (Secker & Walburg, 1974). Meanwhile, Michael and I managed to have one more fight. We traveled to Chicago for a rare screening of a “B” car-racing film, Red Line 7000, among the last works of the great director Howard Hawks. Michael, an extreme Hawks loyalist, declared it a masterwork. I thought it total garbage, and we screamed at each other, insulted each other, on the streets of the Windy City.

Good fortune came to Michael after that. His immense talents as a film critic were recognized when he moved to Los Angeles, wrote for the LA Weekly, and then, from 1984 to 1993, he was a regular reviewer for the Los Angeles Times. In 1993, he became the lead film critic for the Chicago Tribune, where he wrote until 2007. Those who knew him were astonished at his success: Michael was one eccentric individual and hardly a polished one. He grew up with little money, and lived always with, or very near, his equally eccentric artist mother, Edna Wilmington. She accompanied him to screenings until her death in 2009 at age 94. In Los Angeles, I visited them in their home in a creaky motel suite weighed down by books, LPs, VHS movie tapes.

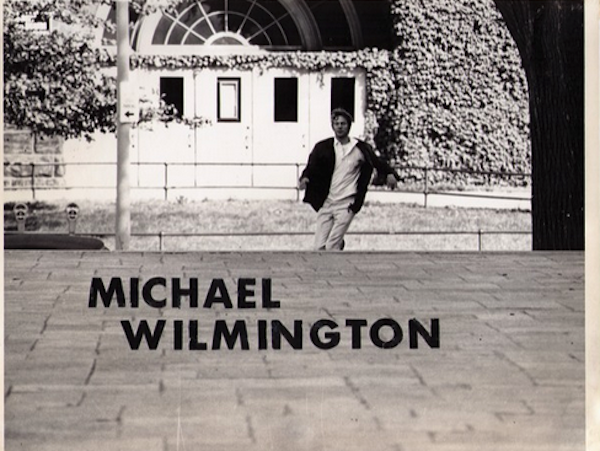

The late Michael Wilmington. Facebook

Michael acted twice in productions of The Zoo Story directed by McBride. Playing Jerry, he dressed all in black, and never after changed his wardrobe. With his leather jacket, dark clothes, usually unkempt hair, Michael was hardly the respectable “face” of prestigious newspapers. But he was kept employed by being such an excellent and knowledgeable writer. Readers could feel his almost religious devotion to cinema. He truly loved all kinds of films, went everywhere to see them, from tiny-budget independents to Hollywood blockbusters. A hard-nosed film critic myself, I thought Michael was too easy on movies, going out of his way to find some good in almost all of them. And here’s my theory of how Michael, an outlier, kept such coveted jobs for so many years. The studios, I believe, were pleased to have Michael in the critic seat because he was so sincerely kind to Hollywood product.

And what of our fractious relationship? It mellowed over time. I can’t speak for myself, but Michael became a very sweet person. A pussycat. When I came to L.A., I drove Michael and Edna all around the town visiting the grave sites of our favorite movie stars. When I directed the 2009 documentary For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism, Michael was a major character; and my film lamented his unceremonious dismissal from the Chicago Tribune.

Until his health seriously deteriorated, Michael continued writing film reviews from his home in L.A., for a website, the Movie City News, and sending pieces back to Madison for the alternative paper Isthmus. The last time I saw Michael was at a film festival in Minneapolis, where he was proud to be followed about by a guy with a camera making a feature documentary about him. We need that film completed: a celebration of film criticism at its best and richest, and a celebration of Michael Wilmington, a unique guy, and friend, whom I knew for 53 years.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

[…] Gerald Peary On Michael Wilmington […]

Great article Gerald. Thank you for keeping Michael’s memory alive for all of us.

Wait a minute! You just wrote a lovely remembrance of somebody who often behaved irascibly and missed deadlines and got into fistfights about movies. I’m surprised you’re employable, Gerry. You just gave Michael a bad review that turned into a good review. Shouldn’t you be distancing yourself from him, pronto, since he was violent toward you half a century ago? And your main source is having known him for 53 years. Well those are just YOUR facts. What kind of a source are you?

But seriously, this is a splendid, well-observed, first-hand portrait of a guy who cared — really cared — about film, in its many permutations. On a visit to the Chicago Int’l Film Festival I can recall how mopey Michael was because he had watched over 20 films by a Japanese director for an upcoming retrospective and his editor had said, “Just pick the best 3.” And even what he wrote about THOSE was chopped down.

His cluttered desk at the Trib, piled high with books and magazines and newspapers like a written-word version of the balancing game Block Head, looked the way I believe the desk of every truly engaged arts critic should look.

Your generation was fortunate to forge approaches to film in such a lively atmosphere.

I knew Michael too but as part of The Next Generation (1975-83). There’s a lot more to tell as the stuff of urban folklore. When the truth meets the legend, print the legend.

Thanks for this great piece on Michael Wilmington. I never knew him, but enjoyed and learned from reading his film criticism for many years.

Knew him in Madison when I was also a Cardinal critic. Glad I did: he was unique.

A great piece, a singular person..