Opera Album Review: The Great Polish National Opera “Halka” Gets a Spirited and Shapely New Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Stanisław Moniuszko’s Halka struts its stuff, impressively, in this new recording with an all-Polish cast conducted by internationally renowned Gabriel Chmura.

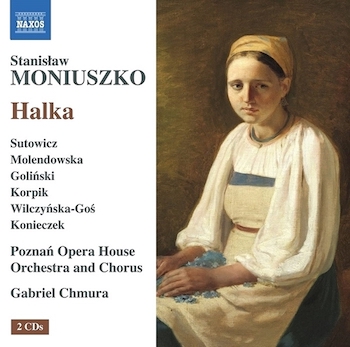

Stanisław Moniuszko, Halka.

Magdalena Molendowska (Halka), Dominik Sutowicz (Jontek), Łukasz Gliński (Janusz), Rafał Korpik (Stolnik).

Poznań Opera House Chorus and Orchestra, conducted by Gabriel Chmura.

Naxos 660485-86 [2 CDs] 117 minutes

Click here to purchase and here to listen to bits of each track.

During the 19th and 20th centuries a number of countries welcomed the arrival of an opera that seemed, to its inhabitants, to embody their special national spirit or in some cases explicitly preached some kind of patriotic message. Or, if the work’s libretto didn’t deal with the nation’s history, at the very least it may have had the makings for a good, effective opera — strong enough to hold an audience’s attention over several hours. Either way, the resulting work could prove (to natives and foreigners alike) that the people or nation in question could inspire cultural products that could measure up to the musical artistry of lands considered more powerful — or more “central,” at least to the opera world (the three reigning traditions there being French, German, and Italian).

During the 19th and 20th centuries a number of countries welcomed the arrival of an opera that seemed, to its inhabitants, to embody their special national spirit or in some cases explicitly preached some kind of patriotic message. Or, if the work’s libretto didn’t deal with the nation’s history, at the very least it may have had the makings for a good, effective opera — strong enough to hold an audience’s attention over several hours. Either way, the resulting work could prove (to natives and foreigners alike) that the people or nation in question could inspire cultural products that could measure up to the musical artistry of lands considered more powerful — or more “central,” at least to the opera world (the three reigning traditions there being French, German, and Italian).

Smetana’s Bartered Bride and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov are the best-known examples — one comical and quasi-universal in its “countryfolk” stereotypes, the other focusing with laser-like intensity on specific individuals from Russian history. Others instances include Granados’s Goyescas (based in part on several of his piano pieces — see my review here), Ölander’s Swedish opera Blenda (a legendary female warrior who, with a troop of women, foiled an invasion by the Danes), Enna’s Danish opera Kleopatra (my review is here), and two wildly different Croatian works: Zajc’s patriotic Nikola Šubić Zrinjski (which I reviewed here) and Gotovac’s delightful love-in-a-village opera Ero the Joker (see my review).

I’ve read about Moniuszko’s Halka (1854, rev. 1858) from time to time but never took the trouble to listen to it. Record magazines have previously hailed three sets some years ago, including one on Le Chant du Monde that featured renowned soloists Stefania Woytowicz and Wieslaw Ochman under Jerzy Semkow. I have also seen mention of a Dux CD that came out in 2009 (conducted by Ewa Michnik) and a Dux DVD released in 2020 (conducted by Piotr Wajrak).

All I mainly know is this new recording, made during a staged performance at the Poznań Opera House (in Poland) in November 2019. I found it completely convincing. The singers sound deeply committed to their roles (it surely helps that they’re singing in their native language), and any slight wobbles and such disappear as the work goes along and the voices warm up. Particularly admirable is Magdalena Molendowska, pure yet warm of voice, as the peasant lass Halka who persists too long in believing that the nobleman Janusz (bass-baritone) still loves her. Janusz has become betrothed to Zofia (mezzo) without telling Halka. Jontek (tenor), who loves Halka in vain, tries to help her see that Janusz is a liar. At the end of Act 2, when she encounters Janusz in the presence of others, he flatly denies ever having known her.

Poznań Opera performs the Highlanders’ Dance from Moniuszko’s Halka.

In Act 3, Halka goes mad and tells her story “as if in a hypnotic trance.” In Act 4, Zofia and Janusz approach the church with the wedding guests. Zofia recognizes the crazed Halka and figures out that the lass and Janusz were once, let us say, intimate. Nonetheless, the engaged couple enter the church for the ceremony. (A lovely canticle is heard from within the church.) Halka, holding her belly, calls out “Our baby is dying” (aha!), considers setting fire to the church to kill Janusz, but then, “sober and calm,” climbs atop a high rock and (anticipating Puccini’s Tosca by several decades, or perhaps imitating Wagner’s Senta from 11 years earlier) leaps to her death in the river below.

Contrasting sharply with these melodramatic tensions among the four main characters are several folklike numbers (plus two, including the canticle already mentioned, that evoke Poland’s deep connection to Catholic worship). An opening polonaise-based number involves many secondary characters, an orchestral mazurka ends Act 1, and, early in Act 4, a passage evokes bagpipes, leading to a dumka-aria for the tenor Jontek. The lengthy opening of Act 3 includes multiple passages in folk style as the pious highland villagers move from their Sunday worship to joyous dancing. (Here we encounter pastoral-sounding “horn” fifths in the harmony, plus a raised fourth degree in the melody such as one finds in Chopin mazurkas.)

In moments of intensity and jollity alike, Moniuszko’s musical language is highly proficient and keenly responsive to the dramatic import of the moment. I should have suspected as much, from having enjoyed his keenly word-responsive Widma, i.e., Phantoms, for chorus and orchestra.

Still, some numbers stand out as particularly effective, such as Jontek’s aforementioned dumka-aria. Halka’s Act 2 soliloquy, “Oh to be a lark and fly out to meet him,” combines the folklike with some brief coloratura, in the manner of Bellini, and even a tiny cabaletta-like ending. As music historian Carl Dahlhaus points out (in his book Nineteenth-Century Music), drawing on style elements generally recognized as “elevated” lent (and still lend!) this naive peasant a dignity — and, I’d say, complexity — that a simple strophic folklike song would not have conveyed. All of which allows us to take Halka’s sufferings more seriously.

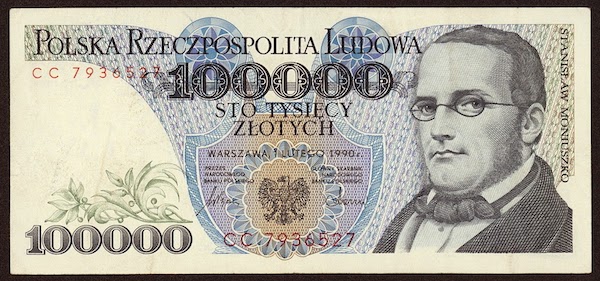

Composer Stanisław Moniuszko on Poland’s 100000 Zloty note

Much credit should be given to the highly capable conductor, the Polish-born Gabriel Chmura. I had not heard him before, though he has been prominent in such cities as Aachen, Ottawa, and (as here) Poznań. His previous recordings have included works by such diverse composers as Haydn, Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling, and Moisey Vainberg.

The sound is lively and well balanced, and the set contains a helpful booklet-essay and synopsis (with track numbers). The downloadable libretto is in Polish and comprehensible English, though it’s been stripped of the crucial stage directions. In short, this recording has the goods, and at a bargain price. Brief applause (just enough) has been kept at the end of each act and a few other numbers.

Coda: I decided to dip into some of the earlier recordings. At times they are as persuasive as this one, occasionally a bit more, occasionally a bit less (e.g., tempos a bit rigid, compared to Chmura’s sensitive inflections). The work has clearly been well served, and repeatedly, on disc. I’m glad to have gotten to know it, finally, and hope it will find its way into opera houses in many lands.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Gabriel Chmura., Magdalena Molendowska, Naxos, Poznań Opera, Ralph Locke