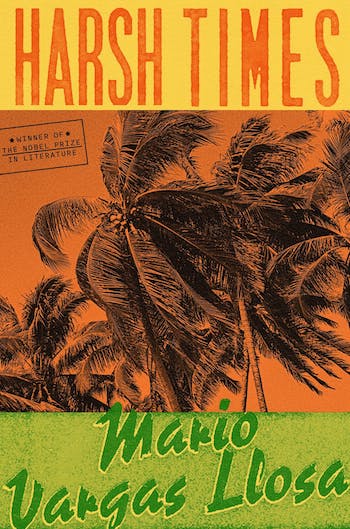

Book Review: Mario Vargas Llosa’s “Harsh Times” — A Menagerie of Monsters Great and Petty

By David Mehegan

Above and beyond Mario Vargas Llosa’s political outlook, his latest novel proves that he remains at heart a master storyteller.

Harsh Times by Mario Vargas Llosa. Translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West. Farrar Straus & Giroux. 304 pp. $28.

The publisher informs us that this novel is “the true story of Guatemala’s political turmoil of the 1950s as only a master of fiction can tell it.”That is like saying, “I’m having a house-painter fix my broken plumbing as only a painter can fix it.” It is not that this intricate and appalling chronicle of cruelty, hypocrisy, and lust for power is less than credible. But we cannot doubt that a novelist’s need for swift action, crisp dialogue, moral clarity, and vivid scenes differs from that of the best historian, who must distrust what she hears that is unverified, look for stacked layers of motivation and happenstance, and allow for the thick fog of ambiguity.

The publisher informs us that this novel is “the true story of Guatemala’s political turmoil of the 1950s as only a master of fiction can tell it.”That is like saying, “I’m having a house-painter fix my broken plumbing as only a painter can fix it.” It is not that this intricate and appalling chronicle of cruelty, hypocrisy, and lust for power is less than credible. But we cannot doubt that a novelist’s need for swift action, crisp dialogue, moral clarity, and vivid scenes differs from that of the best historian, who must distrust what she hears that is unverified, look for stacked layers of motivation and happenstance, and allow for the thick fog of ambiguity.

Having begun with that journalist’s caveat (“If your mother tells you she loves you, check it out.”), I have no grounds to dispute the accuracy of the Nobel laureate’s account. We might ask at first: why Guatemala, why the ’50s, and why “the true story” (is there a false one to disprove?). After all, even Vargas Llosa chooses as epigraph a quote from Winston Churchill: “I never heard of this bloody place Guatemala until I was in my seventy-ninth year.”

But this question reveals an old gringo prejudice: that many of these gang-ridden countries to our south, with their coups and assassinations, their military men weighted down with gold braid- and medal-festooned uniforms, their corruptions and endemic poverty (think of Venezuela and, yes, Guatemala still) are much alike and more or less hopeless and impossible to redeem.

Harsh Times starts with an Ugly American: Boston-based Edward Bernays, the so-called Father of Public Relations (or the Father of Spin, per Larry Tye’s 2002 biography), to advance a campaign against the elected government of reformer Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán on behalf of his client, United Fruit Company. Árbenz in 1952 seized land from United Fruit and gave it to peasant farmers; he also allowed the free development of labor unions.

“Árbenz was sure,” writes Vargas Llosa, “the Agrarian Reform would change the very basis of the economic and social situation in Guatemala, building the foundations for a new society where capitalism and democracy would lead to justice and modernity.”

Democracy, justice, and modernity were not consistent with the feudal interests and methods of United Fruit, which had long controlled several “banana republics” in the region. Liberal values also clashed with a deep class and race chasm in Guatemalan society, in which the Indian peasant majority was regarded as trash by the descendants of the old Spanish ruling class. Convinced by Bernays’s campaign that Árbenz was a communist and a threat to business enterprise in the region, John Foster Dulles and brother Allen Dulles, Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state and CIA director respectively, organized and funded a Bay of Pigs-type invasion by a CIA-trained militia based in Honduras, led by Carlos Castillo Armas, a Guatemalan colonel nicknamed Hatchet Face. A key figure in the American-led effort was the murderous Rafael (El Jefe) Trujillo, longtime US client and dictator of the Dominican Republic, who lent arms and cash to the scheme. In the face of the so-called Liberationist force, in June 1954 Árbenz was forced out, succeeded by Castillo.

As expected, Castillo reversed Árbenz’s agrarian reform, crushed the labor unions, executed thousands of people, and classified 10 percent of the population as communists. However, he failed to repay Trujillo with the butt-kissing honors and emoluments El Jefe had demanded, or with the delivery (“I want him alive”) of an anti-Trujillo Dominican military officer given asylum by Árbenz. So Trujillo arranged Castillo’s assassination, carried out in July 1957. This commenced what would become a chaotic revolving door of military governments, beyond the scope of the novel.

As he tells the story, Vargas Llosa puts himself, and us, inside the minds of most of these characters, as Shakespeare does with the mind of Macbeth. We eavesdrop on the ruminations and calculations of Bernays, Trujillo, John Emil Peurifoy, American “ambassador” to Guatemala (actually a CIA man and a stooge for United Fruit), Árbenz, and Castillo. François (Papa Doc) Duvalier of Haiti also makes an appearance, although fortunately we are spared entry into the gearbox of his demonic mind.

Just below the top power level is a set of three vivid and loathsome characters. There is Lieutenant Colonel Enrique Trinidad Oliva, another ambitious Guatemalan officer, and the extraordinarily ruthless and brutal Johnny Abbes García, a Dominican former journalist and Trujillo enforcer and hit man. This duo carries out the murder of Castillo. Finally there is the crafty Martita Borrero Parra, nicknamed Miss Guatemala, who plays a sort of Isabel Perón to her lover, Castillo, and always seems to land on her feet. After the assassination, she is spirited out of the country by Abbes and becomes his lover for a time.

Mario Vargas Llosa. Photo: Morgana Vargas Llosa

One feature of most of these minds — except for Árbenz, a decent but naive and hapless believer in justice and democracy — is their moral imbecility. However evil, they have a way of justifying themselves to themselves, as we listen in. Contemplating the elimination of Castillo, Trujillo thinks, “He’d made a mistake with the good-for-nothing Castillo Armas, the Generalissimo had no doubt about it. He hadn’t done even one of the three things asked of him, and to top it, the bony, consumptive-looking colonel with the Hitler mustache and sheared skull wasn’t content to snub his proposals — now he was talking bad about [Trujillo’s] family…. The Generalissimo felt one of those jabs of rage that struck him every time he found out someone had spoken ill of his children, his siblings, or his wife — not to mention his mother. The family was sacred to him; whoever slighted them had to pay. And you’ll pay, you bastard, he thought.”

We spend more time in the mind and career of Abbes than any other character, and witness his fate under his last employer, Papa Doc Duvalier — two of a kind, without doubt, except that Duvalier was smart enough to die of natural causes.

I have only sketched this dense though not overlong book, peopled with many other characters whose tangled actions and motivations are reported in detail. After 300-odd pages with this dismal crew, you might crave a shower.

In an epilogue called “After,” the writer steps onstage and addresses the reader in his historian’s voice. The fate of ’50s Guatemala, he argues, was tied up with the evils that later beset so many countries in the region. In particular, the ignorance, national vanity, and obsessive anti-communism of US policy in the Eisenhower era, which employed fanatics like Peurifoy and killers like Trujillo, backfired terribly. That obsession, he maintains, actually worked against American-style democratic reform movements such as that of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, which led to the triumph of Castro and such mini-Castros as Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, as well as the cruel Peruvian insurgency called Shining Path. One might say the same was true of Southeast Asia.

Vargas Llosa, now 85 and author of 26 books, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2010. He is one of those few writers (Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer was another) whose long presence near the center of political action did not contaminate their artistic powers. Strongly leftist in his youth, he ran for president of Peru in 1990 (losing to Alberto Fujimori, now in prison), and over time became a centrist who deplored the dictatorial Castro regime as much as he did those of Trujillo, Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, and Anastasio Somoza Debayle in Nicaragua. His characterizations of great and petty monsters in Harsh Times leaves no doubt of his clear eye for the sinister temptations of power, whether of left or right. He is now a citizen of Spain who has taught at Harvard and spends time in London and Peru. Above and beyond his political outlook, Harsh Times proves that he remains at heart a master storyteller.

David Mehegan, PhD, is the former Book Editor and book-beat writer of the Boston Globe. He can be reached at dmehegan@gmail.bu.edu.