Poetry Review: “Acrobat” — The Beautiful Bengali Poetry of Nabaneeta Dev Sen

By Nancy Naomi Carlson

Translator Nandana Dev Sen has opened a window for us to savor Bengali women’s poetry through these lovingly translated poems of her mother.

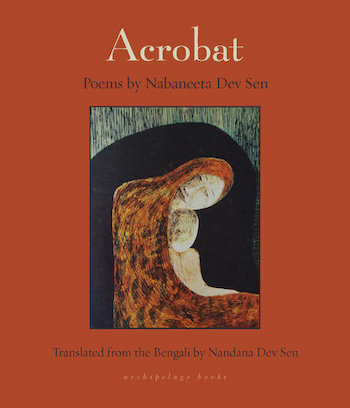

Acrobat: Poems by Nabaneeta Dev Sen. Translated from the Bengali by Nandana Dev Sen. Archipelago Books, 153 pages, $18.

My interest in the rich tradition of Bengali poetry began during my first-ever visit to Kolkata three years ago, where I was a guest of the Seagull School of Publishing, brought there to teach a master class in translation. I found myself in a city unlike any I’d ever seen before — a cacophony of bicycle bells, car horns, English, and regional Indian dialects, as well as a mix of brightly colored saris, exotic spices, exhaust from cars held together by duct tape, and a crush of people going about their daily lives, with some cooking their meals in the streets, the corners of which they’d staked out, guarded by snarling chained dogs. And yet, after I left the din of the street and climbed a dark staircase, I opened the door to the Seagull offices and found myself transported to rooms overflowing with books, mobiles, and astonishingly beautiful artwork — a world like the one of Nabaneeta Dev Sen.

My interest in the rich tradition of Bengali poetry began during my first-ever visit to Kolkata three years ago, where I was a guest of the Seagull School of Publishing, brought there to teach a master class in translation. I found myself in a city unlike any I’d ever seen before — a cacophony of bicycle bells, car horns, English, and regional Indian dialects, as well as a mix of brightly colored saris, exotic spices, exhaust from cars held together by duct tape, and a crush of people going about their daily lives, with some cooking their meals in the streets, the corners of which they’d staked out, guarded by snarling chained dogs. And yet, after I left the din of the street and climbed a dark staircase, I opened the door to the Seagull offices and found myself transported to rooms overflowing with books, mobiles, and astonishingly beautiful artwork — a world like the one of Nabaneeta Dev Sen.

Dev Sen (1938-2019), a critically acclaimed Bengali writer and comparative literature scholar, is considered one of Kolkata’s “greats.” Indeed, she was a recipient of the Padma Shri award, India’s fourth most prestigious civilian honor. She was the only child of two poets and started writing when she was seven years old. Family friends included Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore greatly influenced her life and was the one who gave her her name.

Dev Sen graduated from a college in Kolkata and earned her MA in Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University, then earned a second MA in Comparative Literature from Harvard University. She completed her doctoral studies at Indiana University. While at Jadavpur University, she met her future husband, Amartya Sen, who would later win the Nobel prize in Economic Sciences. Divorced in 1976, Dev Sen returned to Kolkata to raise her two daughters as a single parent — something Indian women generally didn’t do at the time. Also unusual, she spent the next four decades continuing to build her literary and scholarly reputation by authoring over 80 books in Bengali, including poetry, plays, travelogues, novels, short stories, children’s stories with girls as protagonists, and translations. However, Dev Sen wanted to be respected above all for her verse; she was often quoted as saying “I am a poet more than anything else.” Indeed, the artistic and the domestic were at odds within her, as seen in these lines from her poem “Broken Home”: “Do you break your home just for poetry,/ Time and again?” Similarly, in “Make Up Your Mind,” she writes: “Within me/ Breathe two people—/ Make up your mind/ Who do you want/ That woman,/ Or me?”

Dev Sen drew around her an ever-enlarging circle of admirers. Naveen Kishore, publisher of Seagull Books, remembers meeting Dev Sen for the first time in 1984, and shared the following with me in a recent personal communication:

Big deal to be taken to her home one evening by Samik, my founding editor and her contemporary. She opened the door. She was attraction personified. And laughter. Loud and all encompassing. Opens the door. Samik says ‘meet Naveen Kishore, etc., etc.’ She interrupts with wide open arms, pulling me into a vast and welcoming embrace and as I disappear literally into her bosom, she says ‘welcome Naveen Kishore. I have been waiting all my life for you’! Red-faced and excited and confused and totally flushed, it took time for the penny to drop: Naveen and Kishore are two words that mean the same thing. Naveen=evergreen, Kishore=youth. Bengali poets have spent a lifetime writing about Naveens and Kishores. So.

Kishore characterized her as an activist who was never shy about giving her honest and blunt opinion on the topic at hand, and whose poetry, in Bengali, is “fantastic.”

Poet Nabaneeta Dev Sen in 2007. Photo: Wiki Common.

Dev Sen chose to write in Bengali rather than in a language steeped in colonialism. It was a conscious political choice, an expression of her solidarity with those speaking her native regional language. Bengali lends itself to rhyme more readily than English, and it is celebrated for the musicality of its texts. Dev Sen also made use of neologisms, as well as striking images. Her poems are deeply influenced by the classical Bengali literary tradition which incorporates Arabic and Persian literary forms. I’m told by my Bengali-speaking daughter-in-law that written Bengali is very different from the spoken language, and quite difficult to master.

Despite her larger-than-life personality and extraordinary literary career, Dev Sen has remained relatively unknown outside of India. With the publication of Acrobat, Nandana Dev Sen, her daughter and translator, has admirably taken up the cause of expanding the reach of her mother’s poetry. Dev Sen had planned to collaborate with her daughter on this project, but unfortunately died of cancer shortly after she selected the book’s cover art — “Mother and Child” by Rabindranath Tagore. The beautiful artwork reflects the book’s poignant tone: the curved figure of a mother wrapped in a sari is herself enveloping the child held in her lap. The two figures are surrounded by black. A green/black pattern can be seen at the top of the square in which the figures sit, set off from the rust/orange background of the cover, which picks up the color of the mother’s sari.

Acrobat contains five sections, their poems representing six decades of work arranged by theme rather than chronological order: “The Unseen Pendulum,” “I Cage Language,” “Sapling of a Heart,” “Do I know This Face,” and “Sacred Thread.” A list of the poems by publication date can be found at the end of the volume for those wondering when a particular poem was written. For example, the first poem in the collection, “Acrobat,” was written between 2000-2009, and the last, “Return of the Dead,” was completed much earlier, between 1970-1979. This non-chronological ordering of poems, to my eye, engages the reader on a deeper level, and is aesthetically pleasing.

Many of these poems have never before been published in English. While the majority of the poems were translated by Dev Sen’s daughter, we are informed which poems were translated by the author herself, which were originally written in English, and which were translation collaborations with her daughter. The themes include ones relevant to all of us, no matter where we live and who we are, including motherhood, the passage of time, mortality, and the one I felt most drawn to — language. One of my favorites in this section is “Alphabets,” presented below in its entirety.

When night falls

I search for him

I bring him home

I look him in the eye

And I cage

Language

When day breaks

Once again the world

Wraps around my eyes

And off he flies

Taking each word

That alphabet bird

I appreciated the unexpected “cage/language” slant rhyme in the first stanza, as well as this unusual muse-like creature. The assonance of “world/word” is also fresh, and the pure rhyme of “word/bird” seems a fitting end for this language-based poem.

Another favorite from this section focused on language is “Combustion,” below, which underscores the power of words.

As powerful

As that volcano range

Is this range of alphabets

Touch it

And you’ll burn to ashes

Instantly

As I read through Acrobat, I found myself getting drawn in by the distinctive way Nabaneeta looked at life — how her worldview was shaped by living in Kolkata, studying in the United States, and traveling the globe. I was delighted with each new detail I learned about life in India, including evocative references to the sweltering heat of Kolkata, teapoys, Oxfam blankets, monsoons, the Ganga River, cricket, and Lal Ded, a poet and Kashmiri mystic from the 14th century.

Perhaps the most moving poem in this collection is “This Child.” Its first line slaps the reader in the face with a gut-wrenching, rarely articulated truth, but then softens with a comparison of the child’s purity to milk and the promise of life in “this strange and dazzling world.” Below is the poem in its entirety.

One day this child too will die.

This child, pure as milk, whom I’ve brought into this world

with all my heart’s desire, and with fervent prayer.

If she asks me now, ‘On what promise

have you thrust me into this strange and dazzling world?

What grand celebration must I attend?’

I will be petrified.

Choking with fear, with ignorance

I will run away

to a dark cave, numb and empty.

What answer will I give you?

Keep in mind that Acrobat is a rarity: it is a translation of work by a woman author by a translator who is also a woman. According to the translation database maintained at the University of Rochester, translations make up approximately three percent of all books published in America, and the majority of authors are men. The numbers become downright dismal when the data is disaggregated to determine the number of BIPOC women authors living in non-European cities whose poetry gets translated. So Nandana Dev Sen’s invitation to savor Bengali women’s verse through these lovingly translated poems is very much a cause for a “grand celebration.”

Nancy Naomi Carlson, twice an NEA literature translation grant recipient, has published twelve titles (eight translated). An Infusion of Violets (Seagull, 2019) was called “new & noteworthy” by The New York Times, and she was decorated with the rank of Chevalier in the Order of the French Academic Palms. www.nancynaomicarlson.com

Tagged: Acrobat, Archipelago Press, Archipelago-Books, Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Lovely selection of her short poems that gives a taste of this woman poet.