Jazz Appreciation: Remembering George Wein (1925-2021)

By Jon Garelick

The sum total of George Wein’s career was a successful wedding of art and commerce.

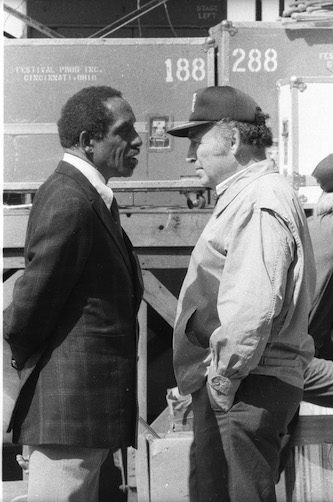

The late George Wein — businessman, musician, and fan.

In one of the handful of times I spoke with George Wein, I mentioned to him how I had recently seen Charlie Haden at Sanders Theatre in Cambridge. The bassist had led a large band along with his quartet, and I’d been appalled by the lackluster attendance.

“Charlie Haden,” Wein said, ”is one of the great musicians in the history of jazz” But, he added, Haden had virtually no ticket-buying audience. Still, if you put him on a festival program, people would listen and enjoy him.

Wein, who died on September 13 at 95, spent a lifetime trying to sell (and occasionally play) jazz. And as such, he was at the nexus of art and commerce, hitching his livelihood to music that became a minority taste not long after he launched the Newport Jazz Festival, in 1954. (The jazz audience has been estimated to be as much as 10 percent of music listeners or as little as 2 percent of record buyers, according to surveys taken in the last 10 years.)

But from that first Newport Festival, Wein banked on jazz. There were plenty of times he went for popular “non-jazz” acts and was ridiculed for it. He booked Led Zeppelin and the Allman Brothers, and paid the price — gate-crashers, “riots,” and banishment by the town that had invited him. As early as 1959 (according to the New York Times obit), jazz critic Nat Hentoff was writing that the Newport Jazz Festival was a “sideshow” and had “nothing to do with the future of jazz.” By the ’90s, many of my jazz-loving peers thought the festival was irrelevant.

But a funny thing happened on the way to irrelevance. In the 2000s and 2010s, a time in which he sold off his production company and then regained control of Newport, Wein opened the Newport Fort Adams site with more stages, and more varied programming. As a result, the festival became a pretty reliable barometer of all that was going on in all facets of jazz. Yes, you could count on the big names — Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock with Wayne Shorter, Pat Metheny, Wynton Marsalis. But there was also Steve Coleman and Ken Vandermark and Dave Douglas, Muhal Richard Abrams with Roscoe Mitchell and Henry Threadgill, Kris Davis, Cécile McLorin Salvant, the large ensembles of John Hollenbeck, Maria Schneider, and Darcy James Argue. And yes, the “crossover” of Dr. John (no complaints here).

George Wein talking to vibraphonist Milt Jackson at the 1982 Newport Jazz Festival. Photo: Michael Ullman

Plenty of big pop names headlined his festivals over the years — Natalie Cole, Ray Charles, Isaac Hayes (again, who’s complaining?). But the sum total of Wein’s career was a successful wedding of art and commerce. Even Hentoff (to quote that Times obit again) allowed, in 2001, that Wein had “expanded the audience for jazz more than any other promoter in the music’s history.”

It was easy to see Wein in later years as a grandfatherly presence at Fort Adams, tooling around with a driver in the “Wein Machine” golf cart, taking in the music and the crowds, offering his benediction, cane in hand, to the crowd from the main stage, playing piano with one of his handpicked Newport All-Stars bands. He and his wife, Joyce (who became vice president of Festival Productions), endowed a chair in African American studies at Boston University. (Joyce died in 2005.) And it was typical of Wein’s cultural acumen, that when he took over the jazz festival in New Orleans, he insisted it be the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, encompassing crafts, history (the Mardi Gras Indian tradition), food (oh, the food!), and a grasp of the region’s music that extended from traditional and modern jazz to R&B, Cajun, Zydeco, and, eventually, rock and hip-hop.

One was always aware, however, of George Wein the businessman, the music promoter who had gone broke at least a couple of times before discovering the miracle of corporate sponsorships (Newport Jazz and Folk eventually went nonprofit). I remember seeing him backstage at Newport, sitting at a small café table, talking to his right-hand man, Danny Melnick, and I stopped by to say hello. We exchanged pleasantries and then, as he saw I was about to launch into a peroration on the day’s events, Wein asked me to excuse him. When I turned around, he and Melnick were bent over that little table, in cordial but intense conversation. After all, he had a business to run. At that point, he must have been in his 80s.

In later years, Wein talked about the importance of developing new talent — and he found artists with popular appeal (Jon Batiste, the real deal), Snarky Puppy (not one of my favorites). After all, he said, Sonny and Wayne and Herbie weren’t going to be around forever. The headliners sold tickets while “the future of jazz” played the small stages.

There were plenty of times at Newport, at a side stage, where I saw people who maybe came to see some of the big jazz stars or pop acts, riveted with hushed attention, and then roaring approval, at shows by Steve Coleman or Rudresh Mahanthappa. Not concert hall headliners, but people who, like Charlie Haden, could get a good response from unsuspecting listeners on a festival bill.

One afternoon at Newport I saw George wheel up to one of the side stages where the Ken Vandermark 5 were playing. Vandermark, at least at that show, was playing what I’d call free jazz over rock grooves (and maybe a few other crazy meters). But that afternoon at Newport, Wein stayed for Vandermark’s entire set, looking totally absorbed, and no doubt taking in an audience that was shouting and cheering throughout (it was one of the most electrifying sets I’ve seen at Newport).

It’s hard to judge a promoter’s opinion of a band — how much of it is based on enthusiasm for the music, and how much on whether they fill the house or flop. But, no matter how big the house, every presenter of music likes to see a connection between audience and performer. Vandermark and his crew were making that connection, not for the thousands out in front of the main stage, but for a couple hundred in the shadow of the Fort Adams wall. I think George Wein was feeling it too. At that moment, he was businessman, musician, and fan.

Jon Garelick is a member of the Boston Globe editorial board. A former arts editor at the Boston Phoenix, he writes frequently about jazz for the Globe, Arts Fuse, and other publications.

It’s worth noting that Wein’s connection with producing jazz precedes his work at Newport by about half a decade. Dick Vacca talks about that period here, also mentioning Wein’s forays as a jazz DJ and lecturer-https://www.richardvacca.com/october-3-happy-birthday-george-wein/

A very well-done recollection and tribute, Jon. Thanks so much for writing this!