Film Review: “Fire Music: A History of the Free Jazz Revolution” — Informative but Incomplete

By Steve Provizer

What’s on the screen rings true, but Fire Music falls short of being fair to history.

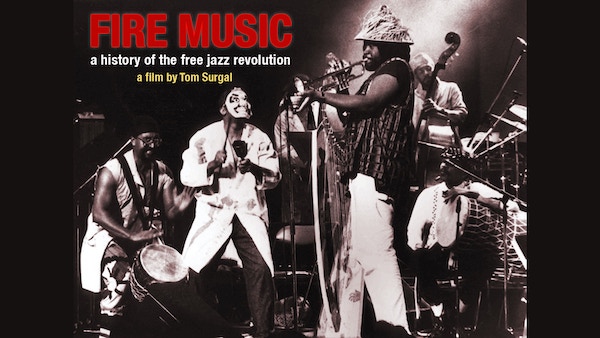

Fire Music: a history of the free jazz revolution, writer/director Tom Surgal.

By the 1920s, despite significant regional and stylistic differences, a musical consensus had formed about what constituted “jazz.” Louis Armstrong’s innovations in the late ’20s represented a significant challenge, but they were not disruptive enough to inspire a significant backlash. Musicians could “hear” what Armstrong was doing and it became infused into the mainstream of the music.

Innovators like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Art Tatum continued to inspire changes during the ’30s, but the first real disruption in the understanding of jazz didn’t occur until the Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie cohort created the music that became known as “Bebop” in the early ’40s. Advanced theoretical ideas about harmony — applied with individual genius and great technical ability — combined to create music that was considered to be different enough from what came before to generate a rift among listeners, critics, and musicians. Many who played traditional or swing jazz reacted with hostility: Armstrong himself famously called it “Chinese music.” Still, it only took a few years for Bebop to assume a central position in jazz. Over the next 10 to 15 years several new streams of jazz developed — and Bebop was foundational to all of them.

Pianist Lennie Tristano experimented with free, non-chordal-based improvisation in the early ’50s, but it wasn’t until later in the decade that disruption genuinely arrived via a movement spearheaded by Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane. The film Fire Music: a history of the free jazz revolution covers that 10-year period, from the late ’50s to the late ’60s. The term “Free Jazz” is a broad umbrella that embraces a variety of styles. To complicate definitional matters, a second term also came into wide use in the ’60s: the “New Thing.” The lines between “Free Jazz” and the “New Thing” were fluid. Examining these diverse stylistic elements offered the documentary an opportunity to explore the diversity of the music. Unfortunately, Fire Music sticks to a single track: we don’t hear about the likes of Grachan Moncur III, Jackie McLean, Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and others who were not closely associated with the film’s chosen interviewees. To encompass the full scope of ‘Free Jazz” these and other musicians who were pursuing new directions should have been included.

The disruptions caused by Bebop and Free Jazz (I’ll arbitrarily include the New Thing in the latter category) shared a number of similarities. Both were spearheaded by Black musicians and carried racial and political connotations. In both cases, many participants adamantly declared that they were artists, not entertainers. As with the inception of Bebop, mainstream jazz musicians were antagonistic. [See my previous article on Ornette Coleman.] However, there were significant differences. One of the most important involved the question of technical merit, which has always been at play in jazz: that is, if you want to prove you belong in the meritocracy, you need to be able to “cut the changes.” Critics of the boppers might not have understood or agreed with the music’s sound or the concept behind it, but they could not doubt the musicians’ technical mastery and credentials.

This wasn’t the case with the free players, who came under attack for not being able to play their instruments. The film provides some famous examples of blowback from other jazz players, including Miles Davis’s savage take on Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman and a story, told by Rashied Ali, of having his cymbal taken away and being dressed down by tenor player Booker Ervin. Coleman was placed in an unusual category because, while he may not have been able to play chord changes, he had a unique voice and created a group that convincingly extended that voice. The blues was always near the surface of his playing and melodies anchored each composition. Coleman’s recording Free Jazz helped solidify the energy in the air and provided a name. But it’s somewhat ironic that the recording was a one-off and doesn’t represent his usual bill of fare. When people went out to hear Coleman, they were not going to hear full-bore examples of simultaneous improvisation by two jazz quartets, as on the Free Jazz album.

John Coltrane, whose role is rightly stressed in Fire Music, and Don Cherry, who gets his due.

The importance of John Coltrane is rightfully stressed in Fire Music. Aside from being an inveterate explorer, Coltrane was a supreme technician who had become a star; he had proved his mettle with Miles Davis and his own groups. His unassailable mastery and mainstream credentials made his support of the Free Jazz movement valuable. The film chronicles that Coltrane got recording contracts for free players, helped to support them financially, showed up at their gigs and hired them for his own groups. Free Jazz exponents make it clear in the film: Coltrane’s imprimatur was so vitally important that, when he died in 1967, much of the air was taken out of the movement. (The absence of Coltrane collaborator Pharoah Sanders from the film is difficult to understand, especially because he’s still around to be interviewed).

The film does not take up the perennial issue of how difficult the music is to listen to. John Tchicai touches on the problem: “People said ‘What the hell is this, it isn’t even music?’” There is nothing in Fire Music about who the musicians thought their audiences were or could be. It is useful to note that, almost until his death in 1967, along with completely free music, Coltrane also played songs like “Afro Blue” and “My Favorite Things.” This was his effort to offer some recognizable guideposts apart from his intense explorations. In the film, Bill Dixon insists that “we weren’t allowed in the nightclubs.” But why were Bebop musicians able to find a home in 52nd St. clubs while “free” players had to largely create their own spaces in which to perform? Only a few non-mainstream players had enough public support for nightclubs to risk hiring them. Indeed, a look at the club dates of that era show almost no gigs for this cohort except Coltrane and Coleman.

The musicians made attempts to find alternative venues in which to perform, like lofts, churches, coffeehouses, and art galleries. In fact, if there was a discernible “movement,” it was because it took a certain amount of collective activity to find gigs. Dixon was the prime mover behind a 1964 event noted in the film called “The October Revolution in Jazz,” a 4-day series of concerts in different New York City venues. Subsequent to that, Dixon formed the Jazz Composers Guild. Personality clashes among the musicians undercut what were some clearly shared elements tying these players together. The group lasted only six months before a number of the musicians broke away and the group evaporated.

Not mentioned in Fire Music is the internecine struggle between The Guild, Amiri Baraka (Leroy Jones), the writer and critic associated with the Black Arts Movement, and Bernard Stollman and his Free Jazz record label ESP‐Disk. Also unmentioned is the organization that spun off from The Guild called the Jazz Composers Guild Orchestra, organized by Carla Bley and Mike Mantler. That effort ultimately led to the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and then, in 1966, to a nonprofit called the Jazz Composers Orchestra Association Inc. (JCOA), which continued until 1975. [See my article on Escalator over the Hill.]

Regarding attempts at organizing like-minded musicians, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), created in Chicago by Muhal Richard Abrams in 1965, was the most successful. In the film, saxophonist Oliver Lake describes picking up the idea from the AACM, bringing it back to St. Louis, and starting the more short-lived Black Artists Group. Lake points out that Europe appreciated Free Jazz before the US. Musicians in Fire Music say that European musicians were not obliged to play blues or swing, intimating they had less to fight against for their music to be taken seriously. As for proof, it should be noted that much of the momentum for the AACM’s success was built up in Europe. Fire Music shows how strong Free Jazz scenes were developed in several countries, most substantially in England, Holland, and Germany. Europeans held Free Jazz musicians in high esteem and were surprised at the lack of respect given them in the US.

Carla Bley, one of the two women interviewed in Fire Music. Photo: Dietmar Liste

Only two women are interviewed in Fire Music, one of whom is German (more on her later); the other is Carla Bley, the only woman we see in period footage in the film. Bley talks movingly about her willingness to live a life of deprivation in pursuit of her music. Alice Coltrane gets no screen time or mention, nor does singer Jeanne Lee. Trumpeter Barbara Donald, whose partner Sonny Simmons is featured in Fire Music, is nowhere to be seen or heard.

When examining the culture of the ’60s, the subject of “spirituality” inevitably arises. The religious impetus driving Coltrane’s musical quest exerted a profound, long-term influence on jazz musicians. It inspired many of them to actively undertake spiritual paths. Examples abound — Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Benny Maupin, and others took up Buddhism. John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana became disciples of Sri Chinmoy. McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders, Larry Young, Billy Higgins, Jackie McLean, and many others became Muslims. This topic is barely covered in Fire Music. Cecil Taylor cites nature as an inspiration for his work and Sun Ra discourses in his own unique trans-galactic way. Much of the conversation here focuses on the fatigue — even disgust — the musicians felt with playing older styles of jazz and the challenges of seeking personal freedom as a means to evolve the music. To paraphrase what Coleman says: machines can do the past, we can do the present. There is also some concrete political talk. We hear about Coleman’s struggle for equal pay with the owners of the Five Spot Cafe. Bobby Bradford and Bill Dixon address the unfair treatment of Black musicians and Archie Shepp compares the struggle of musicians to the wider fight for African American equality.

The only nonmusician talking head in Fire Music (good choice) is the white writer (bad choice) Gary Giddins. If the musicians had been asked the right questions, Giddins’s comments would not have been necessary. I did like one of his bits, his metaphor for how Free Jazz musicians approached their performances: “Let’s take away some of the standard agreements [about jazz] and see if we can still talk with each other.”As for the rest — I don’t agree with his contention that the music of Charles Mingus became more consciously avant-garde because of the Free Jazz movement. Yes, Eric Dolphy was in his band, but Mingus had made self-consciously avant-garde music as far back as the early ’50s. Giddins also tries to make the case that the movement is distinctive because the musicians came from such far-flung geographic areas. I find this point greatly exaggerated. Finally, he tries to explain Coleman’s bending of notes by trying to explain quarter-tones and the difference between the tempered scale and the natural harmonic series. Even if Giddins had successfully put his notion across, it is not a viable explanation — it was not how Coleman saw it.

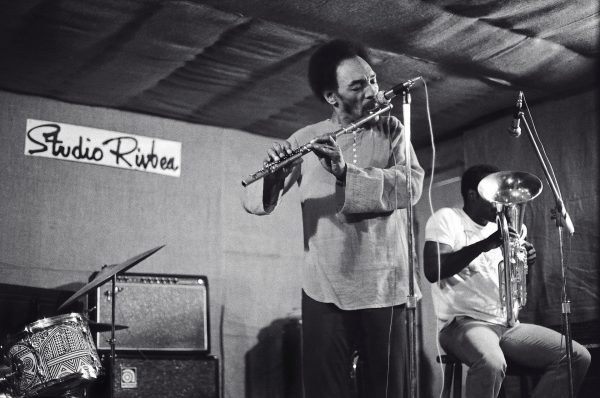

Sam Rivers and Joe Daley at Studio Rivbea in 1978. Photo: Wiki Common.

Don Cherry gets his due here. There’s amusing stuff from European pianist Misha Mengelberg (“I’m a complete fraud”), drollery from Prince Lasha, and an important firsthand story told by keyboardist-vibist Karl Berger and German singer Ingrid Sertso, who ran the Berlin nightclub Dolphy was playing in when he died. They give lie to the story that Dolphy wasn’t properly treated because of racist assumptions, his doctors assuming he was a drug user rather than a diabetic. Berger recalls that when Dolphy was at the hospital: “The doctor said to me he had never seen anyone with as much sugar in his blood.” Unfortunately, Dolphy was past the point of being savable.

We see some of what happens after Coltrane’s death. The loft scene became particularly important. Following Coleman’s Artist House in the ’60s, there was much loft activity in the ’70s — Rashied Ali’s Studio 77, Studio Infinity, Environ, the Ladies’ Fort, Studio WIS, Firehouse Theater, and Sunrise Studios. The film focuses on Sam Rivers’s Studio Rivbea, an important locus of energy from 1970 into the mid-’70s.

There’s no attempt to connect the history of Free Jazz with what is happening now. A couple of screens at the end read: “The new mainstream has attempted to eliminate the innovations of the avant-garde from jazz history”’ and “Since the 1980’s, there’s been a marked shift towards a more commercially palatable Bebop-influenced jazz.” The conspiratorial tone of these messages is overdrawn, as if the expectation is that, if not for the depredations of the Bop-oriented jazz world, free playing would dominate the landscape. Despite combative comments from Wynton Marsalis and silence from Ken Burns, the playing of Free Jazz has, in fact, continued in an unbroken fashion since the ’60s, sometimes in stand-alone units and sometimes as part of the arsenal of musicians who play mostly “inside.”

Fire Music is an attractive and well-edited film, drawing on a lot of inventive visuals, including abstract patterns of light, animations, and multiple split screens. The alternation of interviews with vintage black-and-white and color footage is well paced. If you know and like the music, you’ll be happy to see the film clips from the era. If you don’t, there’s enough visual interest and interesting stories to get you through the performance clips, none of which, in any case, are particularly long. If I judge Fire Music harshly in some ways, it’s because the documentary feels incomplete: it leaves out a number of important artistic movers-and-shakers, doesn’t dig deeply enough into crucial variations in musical approaches, and doesn’t address some of the significant internecine power elements riling up the jazz scene at the time. It’s not that what’s on the screen doesn’t ring true, it’s that the lack of context reduces its value as a historical document.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: documenary, Fire Music, Fire Music: A History of the Free Jazz Revolution, free jazz

Thanks for your comprehensive review, Steve. That a filmmaker attempts to document such a widespread and multi-faceted topic is in itself admirable, whatever the inevitable exclusions. “Free jazz,” “fire music,” “the new thing,” whatever it’s called continues as a powerful strain of international jazz-derived activity. The notion that it was a historical moment and comprised a batch of musicians’ affiliations is, I believe, erroneous. I’ve never heard Carla Bley, a wonderful composer/arranger/orchestra leader, play “free,” and of course “Free Jazz” itself had structures. There’s a lot to dig into (and to dig).

Good review, Steve. Interesting that you mention Coltrane continuing to play “Afro Blue” etc. well after he began playing free. I am reminded of an interview Len Lyons did with Red Garland in the early ’80s, which is included in his book, The Great Jazz Pianists. Garland said he asked Coltrane if he had faith in what he was doing, and Coltrane replied, “Yeah, sort of. But I got myself out here, and now if I turned back and started playing the way I used to play, people would think I was a phony. I’d lay a lot of the cats right out because they’ve been following me.” So what would have happened if Coltrane had gone off and recorded an inside-facing album in 1968, had he lived? Fun to think about.

That is indeed interesting, Dick. Although far from a definitive statement from Trane, it does open the door a crack–and why not? Every time he changed his music, he left people behind who were sure he’d finally reached the end of his journey. Why not another trip in a new direction?

No Mention to the Vision Fest running in NYC every year …..

As I say in the piece: “the playing of Free Jazz has, in fact, continued in an unbroken fashion since the ’60s…”

Steve, you know a hell of a lot about Free Jazz and you write beautifully and knowledgeably. There is so much to learn from your article. But as a documentarian myself, I find it wearying when lectured about all the things missing from my film. There is only so much that can be put into a film to keep it streamlined and understandable. Things of importance invariably fall away. A documentary is not a book. Steve, you are too hard on this film. You are asking for a book with lots of chapters, not a movie. Not that some of your charges couldn’t have been rectified: more women, Pharaoh Sanders, something about spirituality.

Gerald, I take your point. It’s hard, though, to draw the distinction between what one thinks any documentary about a certain subject should contain and the grain of salt that should be applied given all the uncontrollable exigencies built into the process. It’s a judgement about the difference between telling a story that is not complete and one that, in some ways, is just not true — a delicate balance. And maybe because there aren’t a lot of general-interest forums to discuss what at this point is pretty esoteric stuff, I can get a little, let’s say, preachy.

“Only 2 women…white writer (bad choice)” way to shoehorn the wacky ideas of the modern left into a review about a jazz documentary. You’re white. If you were asked to comment on this subject for the documentary, would you decline? If you have a problem with Gary Giddins, a person whose documented and written about jazz for 40+ years, fine. What his race has to do with it is baffling. Also, 2 women? Can you name 5 women that had a integral role in the creation of free jazz? Can you even name 3? What a weird lens to watch a documentary about music through.