Opera Album Review: A First-Rate World-Premiere Recording of a Short Baroque Opera about the Young Aeneas

By Ralph P. Locke

I don’t recall encountering a recent Baroque recording that is sung with such a fine balance of smoothness and character.

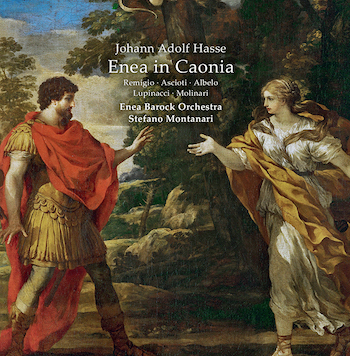

Johann Adolph Hasse: Enea in Caonia

Carmela Remigio (Ilia), Francesca Ascioti (Enea), Rafaella Lupinacci (Andromaca), Paola Valentina Molinari (Eleno), Celso Albelo (Niso).

Enea Barock Orchestra, cond. Stefano Montanari.

CPO 555334 [2 CDs] 104 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

This world-premiere recording of a short opera from 1727 by Johann Adolf Hasse (1699-1783), a near-contemporary of Bach (but better known and paid), seems at first to have been put together for the purpose of letting us hear this one long-forgotten work by Hasse. The alto Francesca Ascioti, who sings the title role of Enea (Aeneas), is listed as “project manager,” and the Enea Barock Orchestra bears the same name as well.

This world-premiere recording of a short opera from 1727 by Johann Adolf Hasse (1699-1783), a near-contemporary of Bach (but better known and paid), seems at first to have been put together for the purpose of letting us hear this one long-forgotten work by Hasse. The alto Francesca Ascioti, who sings the title role of Enea (Aeneas), is listed as “project manager,” and the Enea Barock Orchestra bears the same name as well.

But the booklet implies that this newly founded orchestra (which involves musicians from many countries and is headquartered in Rome) will continue to explore other Baroque-era works that in some way cross the mountainous boundaries that separate Italy from lands to the north. The initiative sounds valuable, given the extensive cultural cross-influences between the Italian peninsula and the German-speaking lands (to which they could reasonably add the French- and Flemish/Dutch-speaking ones as well). Hasse is a natural focus: originally from Bavaria, he made his early career in Italy — where he composed the work heard here — and then brought Italian-style opera and church music north to Dresden (in Saxony).

I was inclined to like the recording the moment I noticed that it involved Ascioti, a marvelously intelligent alto, whose singing I found at once beautiful and dramatic in a Cesti opera (see my review), and because I was so taken with the two Hasse operas that I happen to know: Attilio Regolo and the one opera of his that is relatively familiar today, Cleofide. Plus some very fine arias that he wrote for Il Tigrane, to be sung by “the Other Cleopatra”: princess of Pontus and future queen of Armenia. (See my review of Isabel Bayrakdarian’s recent and beautifully poised recording of Cleopatra’s arias from operas by Hasse, Vivaldi, and Gluck.)

I was not disappointed. The plot is simple but intriguing for anybody who knows a bit of Roman history. Here we reencounter Aeneas and Andromache, but in an episode from before Aeneas’s arrival in Carthage, so there’s no Dido. Instead, we are among the Chaonians in Epirus (a region in northeastern Greece that today laps over into southern Albania).

Andromache has married the young king Helenus (Eleno), and the two of them end up encouraging Aeneas to continue on his gods-ordained path (which, we know, will result in the founding of Rome on the Tiber). Some depth is added by Andromache’s continuing sorrow over her late husband Hector; and some tension, by the infatuation of King Nisus of Chaonia — Niso, a former wartime buddy of Aeneas — with Ilia, “a humble Trojan huntress who dwells in the woods of Chaonia” and who finally rejects Niso in order to remain free.

From the opening sinfonia and Enea’s first aria to the brief closing chorus (which here means “number sung by all the solo singers together”), the score brings delight after delight. Though the work is of course basically a series of da capo arias, Hasse often lends specificity to a number through intriguing string figurations or some other instrumental color. A pair of horns in the first aria sung by Niso suggests to the alert listener that Niso is a hunter, a fact that Enea confirms in recitative soon thereafter. A second sinfonia (borrowed from a different Hasse opera, and nearly seven minutes long) opens Act 2 and brings lots of incisive entries for the oboes and energetic (but well-controlled) scurrying and slashing in the strings.

Enea in Caonia is an example of a serenata: an opera intended, often, for performance at a private palace — such as to honor a wedding or christening — and therefore on the short side and requiring few singers and minimal staging. Hasse composed it relatively early in his career, possibly on the occasion of a joint visit to Naples (which was then under Austrian rule) by Violante Beatrice, daughter of the elector of Bavaria, and her nephew Clemens August, the elector of Cologne.

In this case, we have five characters, two female (Ilia and Andromaca) and three male. But prominent male roles in Italian operas in those days were often assigned to castrati (or occasionally to female singers). Such roles are nowadays assigned either to a female singer, a countertenor, or (usually the worst solution) a baritone singing the part an octave too low. In the present recording, only Niso, a tenor rather than castrato role, is sung by a male. Put differently, if you love Baroque music but can’t abide countertenors (and I know some music lovers who can’t), this recording is just right for you.

I should mention two wonderfully creamy sopranos: Carmela Remigio, whom I had discovered with great pleasure in Donizetti’s Il Castello di Kenilworth (Sept/Oct 2019), and Paola Valentina Molinari, as the young king of Epirus, Helenus (Eleno). Molinari gets to sing the work’s one accompanied recitative, in which Helenus — who, as in Virgil’s Aeneid is a kind of seer — foretells Aeneas’s future struggles and his victorious founding of Rome, on the Tiber. (This is CD 2, track 20. All the tracks numbers in the libretto are too low by one for CD2, because somebody forgot to number the inserted sinfonia that starts the act off.)

Soprano Carmela Remigio in the CPO recording session for Enea in Caonia.

I don’t recall encountering a recent Baroque recording that is sung with such a fine balance of smoothness and character. (The only disappointment comes from the one male singer, Celso Albelo, whose breath is not always fully supported.) Just listen to the way that alto Ascioti, in Enea’s first aria, breaks up some of Hasse’s florid lines into joyously unconnected notes, suggesting laughter. Or how Andromaca (“mezzo-soprano” Lupinacci, who sounds like an alto to me) gives vent to her sorrow over the death of her beloved Hector in her first aria. The booklet credits Vivica Genaux (one of my favorite singers) with having coached the cast members.

(The entire recording can be heard, in separate tracks, on YouTube — or, at least for the moment, as a single long file — and, smoothly joined, on Spotify and other streaming sites. The beginning of each track can be heard here.)

It surely helps that most of the singers are native Italian-speakers. This reinforces a point that I’ve made in a number of my recent reviews for the Arts Fuse about how much more communicative singers are in a language they speak fluently. And this can be true even when the work is sung in translation, which is not the case here, but is in an instance I have drawn attention to here: the first-ever recording of the German version of Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari’s I quatro rusteghi (Die vier Grobiane), sung almost entirely by native German-speakers.

The recording was made in the Villa Torlonia in Rome in September 2019. I hope that, as the pandemic recedes, the Enea Barock Orchestra (a name mixing Italian and German words in German word-order!) will resume its intended project of bringing forth more works of the period that crossed the borders between Italy and its northern neighbors. This Hasse release augurs well for their success.

Fine booklet, with an essay by Hasse authority Raffaele Mellace and the full libretto, all well translated. But a track list should certainly name the character singing, not the singer. It puts a stumbling block in the path of the reader trying to flip quickly between track list and libretto.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Carmela Remigio, Enea Barock Orchestra, Enea in Caonia, Johann Adolph Hasse

[…] Recordings Opera Album Review: A First-Rate World-Premiere Recording of a Short Baroque Opera about the Young Aeneas: Johann Adolph Hasse: Enea in Caonia artfuse.org […]