Film Commentary: Dorothy Davenport — Neglected American Female Cineaste

By Gerald Peary

The Road to Ruin is a practically unknown film begging for discovery, and to be championed as a startling example of pre-Code cinema. And as a keystone for creating a directorial reputation for “Mrs. Wallace Reid.”

Director Dorothy Davenport, who called herself Dorothy Reid on one film and “Mrs. Wallace Reid” on three others

As a scholar of pioneering filmmaker Dorothy Arzner, I have always described her as “the only American woman with a directing career from the late silent era through the early 1940s.” (A one-movie exception was Wanda Tuchock, co-director of 1934’s unmemorable Finishing School.) But a May 31 item in The New Yorker by critic Richard Brody alerted me to another female cineaste, with his favorable write-up of a film called The Woman Condemned (1934) made by a Dorothy Davenport. Who? I had only a dim idea. But research showed that Davenport had a substantial directorial career. She was the credited filmmaker or co-filmmaker of at least six feature films going back to 1923.

Actually, many women had directed movies in the wide-open 1920s and even before, the most prominent being Alice Guy Blache and Lois Weber. But Davenport persisted, after almost all other women had been drummed out of the increasingly sexist and studio-dominated motion picture business. As for Dorothy Arzner, I must amend my description: she was the only woman between 1927-1941 with a Hollywood directing career. Dorothy Davenport made her films as low-budget independent works always outside of the studios. Between 1929 and 1934 she was director or co-director of four such indie features, three of these sound films. But not once did she use her maiden name. Choosing to honor her late husband, she called herself Dorothy Reid on one film and “Mrs. Wallace Reid” on three others.

Have any other films in the whole history of cinema been credited to a “Mrs”?

A little backstory: Dorothy Davenport was born in Boston in 1895, coming from a several-generation family of stage actors and then film actors. At 16, she moved from Massachusetts to Southern California for her own acting career. At Nestor Studios, she met a fellow thespian, Wallace Reid. They fell in love, married, and, after working on many pictures together, Davenport left movies in 1917 to become a full-time mother. Meanwhile, her husband had risen to be a bonafide movie star. But tragedy: Wallace Reid became addicted to morphine after an injury from a train wreck. He died of his addiction in 1923, an event which made newspaper headlines. And at this point, Davenport returned to movies, producing and starring in the film, Human Wreckage (1924), a warning against drug use. She would appear live with the movie and even met at the White House in 1925 with Calvin Coolidge to discuss drug problems in America. (Unfortunately, Human Wreckage is a lost film.) She continued as a “social conscience” filmmaker, producing The Red Kimono (1925) about white slavery and prostitution. As producer, she started to call herself “Mrs. Wallace Reid.”

Reid (I also will call her that) was active on the set for the movies she produced. Some witnesses attest that she was the uncredited co-director. For Reid’s variety of skills, she caught the attention of Willis Kent, an enterprising independent producer who made both imitation Hollywood films and more sensational exploitation pictures. Kent, the future producer of the notorious Cocaine Fiends (1935) and The Wages of Sin (1938), saw someone in Reid he might profit by considering the titillating subject matter of her social consciousness works. This was their business arrangement: Mrs. Wallace Reid Productions would be released through Kent’s variously named independent companies (“A Progressive Picture,” etc.), with Reid as the designated filmmaker.

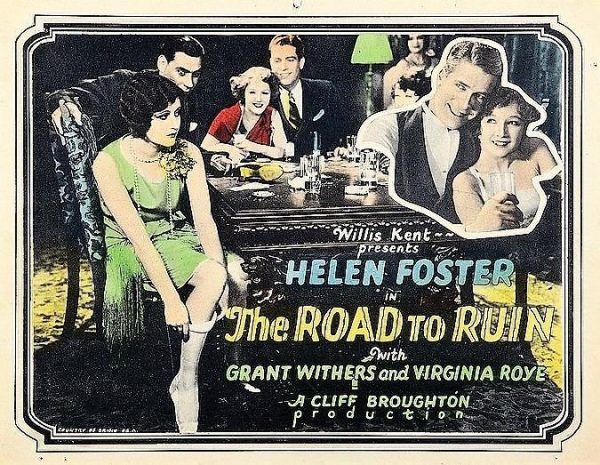

Their first collaboration, Linda (1929), was not an exploitation film but a typical rural melodrama of the late silent era, in which a country girl (Helen Foster) is forced by her father to marry an unattractive local (Noah Beery) when her heart yearns for a sophisticated doctor (Warner Baxter). Willis Kent must have had money in pocket at this time. The production values are the highest of any of the films Reid would make under his auspices, and the two male leads were played by name Hollywood actors. As for Reid’s direction, it is quite smooth here, occasionally inspired. At her best, she is a competent filmmaker, though often missing (for me) Dorothy Arzner’s intense connection to her female characters.

In 1932, Reid was a screenwriter for Kent’s production of The Racing Strain, a racetrack drama starring her son, Wallace Reid, Jr. She returned to acting in Man Hunt, a 1933 RKO mystery, appearing as “Mrs. Wallace Reid” and playing the mom of a teen detective. Also in 1933, Kent and Reid collaborated for a second time as producer and co-director (she with Melville Shyer) of Sucker Money, a dreary, poorly executed drama about a young journalist aiming to unveil the fakery of a mercenary spiritualist (Mischa Auer). Kent’s title card for the movie promises “An expose of the psychic racket. True Life Photoplay.” Neither is delivered in this lame film which ends with the newspaperman positing a career switch to becoming a small-town Wisconsin banker. “In Oshkosh? Yes, in Oshkosh.”

The Woman Condemned (1934), directed solo by Reid, is certainly better than Sucker Money. Still, it’s a pretty stiff murder melodrama with a strained denouement and a gooey happy ending. And there’s not much screen presence from the “B” movie star, Claudia Dell, whose name in the credits is, inexplicably, above the title. However, there is one curious episode, which Richard Brody understandably mentioned in his New Yorker piece. It’s the closest Reid comes to a pre-feminist moment: a night court scene in which all the accused are unfortunate women, including two before the male judge for “soliciting.” And there is one woman sitting on the bench with a not-explained black eye. Is she a victim of domestic abuse, yet the one who is arrested?

Also in 1934, Reid co-directed (again with Shyer) what would be her last feature. It’s The Road to Ruin, a remake of a 1928 silent produced by Kent and, in both versions, starring Linda’s Helen Foster. Reid’s last time behind the camera resulted in her most arresting work by far, a film released just before the Hollywood Code went into effect and which challenges the Code in many of its eye-popping scenes. Let me say it clearly: The Road to Ruin is a practically unknown film begging for discovery, and to be championed as a startling example of pre-Code cinema. And as a keystone for creating a directorial reputation for “Mrs. Wallace Reid.”

Scene featuring an abortionist in The Road to Ruin.

I said earlier that Reid began as a “social consciousness” filmmaker, as someone sympathetic to drug addicts and women forced into prostitution. The Road to Ruin has a more conservative point of view, indicating how, step by step, a prudish young girl’s decision to start kissing boys and drinking and smoking leads to sexual permissiveness, an intervention by a vice squad, a botched abortion, and, yes, a very premature death. The movie’s overt moral is: young women, don’t indulge! But Reid is adhering here to the sly exploitation vision and strategy of producer Kent. That means: fill the screen with all the sexy, explosive things that you are condemning.

Kent and Reid in tandem are, here, breathtakingly transgressive. After several nervy fadeouts which suggest that Ann, our heroine, is about to partake of premarital sex, there’s a wild party in which the women go down to their underwear in a coed game of “strip” dice-throwing, and then, barely clad, leap into a swimming pool. Those licentious scenes are only foreplay for what follows, as The Road to Ruin boldly moves into daring territory for even a pre-Code movie.

I have never seen this ever in any American film: when Ann and her female friend are arrested at the party, they are made by the police to submit to a “physical exam.” What could that mean except checking to see if their virginity is intact? After they are examined off-screen, we are shown on-screen a medical report with the results: Ann, whom we know has slept with two men, is labeled a “sex delinquent.” And the second amazing scene: a pregnant Ann is taken by the man who impregnated her to an abortionist. There is a vivid shot of the abortionist opening the door to a frightened Ann onto his shady operating room, before she submits to what proves fatal: “a clumsy, unsanitary operation.”

The Hollywood Code, in force several months after The Road to Ruin’s spring 1934 release, would make sure that even just saying the word “abortion” was verboten. There would certainly be no more “physical exams” in movies to see if a woman was having sex. On the other hand, the Code enforcers would have heartily approved of The Road to Ruin’s conclusion, Ann dying for her host of sins. As film historian Thomas Doherty so wisely noted about how the Hollywood Code was applied: films didn’t have to end happily. They had to end “morally. “The Road to Ruin precisely.

I don’t know much about the 1934 reception to Reid’s movie except that it had trouble with censors, and that the state of Virginia asked for many cuts. But it doesn’t seem that The Road to Ruin’s tarnished reputation led it to fame and notoriety or, for Willis Kent, the desired profits. Only to obscurity and, until now, erasure from film history.

Though her directing career was over (we don’t know why), Reid continued an employment in films until 1956, most often as a producer, occasionally as a screenwriter. She shed “Mrs. Wallace Reid.” She was Dorothy Reid. None of her

18 or so films post-directing is an important one, but she provided the script for the well-loved Rhubarb (1951), about a cat that inherits a baseball team. Perhaps her most skilled work was writing the screenplays for two well-done film “noirs,” Impact (1949) and Footsteps in the Fog (1955). The latter was directed by Arthur Lubin, with whom she often collaborated as a writer or producer.

Alas, her employment in movies through the years made her no more publicly recognized. In 1977, Dorothy Davenport/Dorothy Reid/”Mrs. Wallace Reid” died at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital at age 82. There doesn’t seem to have been a NY Times or LA Times obit. She is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, among other film actors and directors. And where her husband, Wallace Reid, also is interred.

Does anyone ever visit her grave? I would hope so, maybe encouraged by this appreciative article.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His new feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, is playing at film festivals around the world.

Thank you so much about writing about my grandmother. She was truly amazing. As a child I listened while she and her friend Tommy Burbridge wrote “Footsteps in the Fog”. She also did Frances the Talking Mule programs on TV, a program or two with Loretta Young, among others.