Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (April Entry)

From one-hit wonders loaded with personal memories to timeless masterpieces that still speak to new generations, the April edition of the “1971 Project” hails more superb sounds from a year of political turmoil and cultural experimentation. So, pull down the zipper and take a look below at this month’s list of great music celebrating its 50th anniversary.

For those who missed them, here are the entries for February and March.

Also, what does this music mean to you? Let us know in the comments.

— Allen Michie has graduate degrees in English Literature from Oxford University and Emory University. He works in higher education administration in Austin, TX (home of Armadillo World Headquarters, which was just getting fired up in 1971).

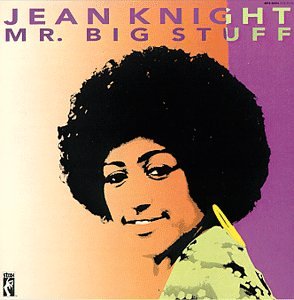

Jean Knight: “Mr. Big Stuff” (Stax Records)

“Mr. Big Stuff” may be a bit of nightclub fluff that likely wouldn’t make the cut on many dance playlists now. I doubt I even knew Jean Knight’s name in 1971. But I remember when, not long out of the army, I would go with my girlfriend Pauline and her sisters to dance at Lucy in the Sky in Brighton and Heartache in Allston. “Mr. Big Stuff” was part of our soundtrack to romance and escape.

“Mr. Big Stuff” may be a bit of nightclub fluff that likely wouldn’t make the cut on many dance playlists now. I doubt I even knew Jean Knight’s name in 1971. But I remember when, not long out of the army, I would go with my girlfriend Pauline and her sisters to dance at Lucy in the Sky in Brighton and Heartache in Allston. “Mr. Big Stuff” was part of our soundtrack to romance and escape.

The Vietnam war was lurching toward its eventual collapse, though that was some years away yet. There was still one more term of that most toxic presidency in American history (until this one just ended). We had Richard M. Nixon, who would be elected a second time by every state except the single sane Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which alone would claim the moral and mental high ground and deny him total victory. “Mr. Big Stuff… /Tell me who do you think you are?”

No, the song’s not a comment on Nixon. Screw him, it could be anyone, whomever you wanted it to be. It’s the beat, baby. The magnetic pulse that, for a short time at least, allowed you to forget one reality and forge ahead into an imagined one, writhing under the strobe lights that let you be intimately part of something communal and, simultaneously, as isolated and alone as a person consigned to an asteroid. “Mr. Big Stuff… /You’re never gonna get my love… “

For five weeks the song was No. 1 on Billboard’s Soul Singles. It went double platinum, was nominated for a Grammy, and has been sampled and covered by more than a dozen artists.

And then there’s this: the all-female heavy metal band Precious Metal released a cover of the song on their self-titled 1990 album. A well-known businessman originally appeared in the band’s music video. But, ignoring the fact he’d agreed to a $10,000 appearance fee, the dude demanded $250,000. Wisely, the women in the band said drop dead, as women have been telling him for decades, and he was replaced in the final version of the video. His name was Donald Trump. “Cause when I give my love, I want love in return (oh yeah)/Now I know this is a lesson Mr. Big Stuff you haven’t learned…”

— David Daniel

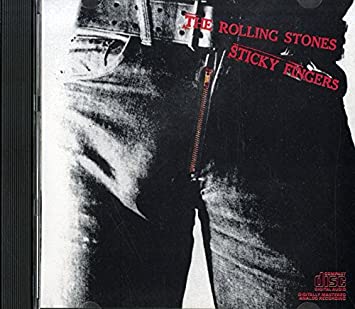

The Rolling Stones: Sticky Fingers (Rolling Stones Records)

Let’s get the externals over with. Sticky Fingers is the first on the band’s own label — Rolling Stones Records. The title is patented Stones adolescent naughtiness, the fingers in question obviously sticky with libidinal effusions. And then there’s the award-winning Andy Warhol cover. The close-up is of a male torso, the bulge of a tumescent organ visible; the crowning touch is the fully functional zipper revealing a photo of white underpants when unzipped.

Let’s get the externals over with. Sticky Fingers is the first on the band’s own label — Rolling Stones Records. The title is patented Stones adolescent naughtiness, the fingers in question obviously sticky with libidinal effusions. And then there’s the award-winning Andy Warhol cover. The close-up is of a male torso, the bulge of a tumescent organ visible; the crowning touch is the fully functional zipper revealing a photo of white underpants when unzipped.

So, name, cover, zipper: cocky naughtiness reaches full-extension, so to speak. The first hit single was “Brown Sugar,” a blatant tribute to the sexual appeal of dark-skinned women. Another song is titled “Bitch.” (Both are first-rate upbeat movers.) And the effectively ominous “Sister Morphine”? A more upfront drug song is hard to imagine. Yet for all its calculated outrageousness, the elegantly produced Sticky Fingers is not far off the Stones’ superb late ’60s peak.

On “Sway,” every instrument plays behind the beat, creating a mesmerism of shifting surfaces and jagged rhythms. Mick Taylor and Charlie Watts shine. Its lyrics are nearly impossible to discern. I just looked them up and was newly impressed: a dirge of death-infused drug-addled disaffection, with a purposefully vague, possibly upbeat last verse. The girl in bed smiles. What does it mean in the context of evil and death and drugs?

The balladic highlight, for me, is “Moonlight Mile.” Pure serious heart and soul, no theater, all essence. A song drenched in the alienation of the road, and the attendant yearning for a true love far away. This is the lone ballad where Jagger sounds emotionally available and genuinely honest. It’s obvious the man knows loneliness.

“I Got the Blues” also has soul, Mick in a comfortable R & B pocket. In “Wild Horses,” Mick leans heavily on his onstage posturing. The lament for being alone seems less authentic here. Jagger messes with the ancient “You Gotta Move” — it’s an almost clownish imitation of an old rural blues singer, like aural blackface. His twanged-up white country singing on “Dead Flowers” seems just jokey. “Morphine,” meanwhile, is a theatrical triumph.

Who is Jagger? Sexy and sexist, lover and hater. He’s spent a lifetime as a soul singer with a nasty, embittered heart. His unknowable center may be the key to some of the fascination he evokes. But at times he and the boys live up to the PR line “the world’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll band.” In memory, it seems every Cambridge party I attended in the ’70s hit a dance frenzy with the brilliant “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’.” Keith Richards and saxman Bobby Keys lead the abrupt shift in gears mid-song, and the ever-rising Santana-like rave-up lifts off to an inspired stratosphere. Even white male academics found themselves out of control, deliriously dancing.

— Daniel Gewertz

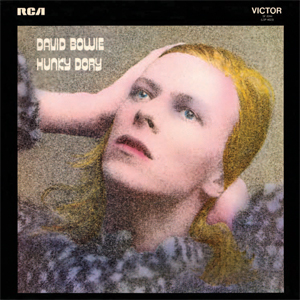

David Bowie: Hunky Dory (RCA Victor)

By 1971, David Bowie himself probably didn’t realize how great he was going to be. He’d already written a couple of well-received songs like “Space Oddity,” and yet his records weren’t selling as much as his management had hoped. He’d just come off of touring behind The Man Who Sold the World, which had been met with intrigued reviews and a different cover for the American market. Most importantly, it was a make-or-break moment for him. Hunky Dory ended up turning that crisis into opportunity and made what I think is his greatest record.

By 1971, David Bowie himself probably didn’t realize how great he was going to be. He’d already written a couple of well-received songs like “Space Oddity,” and yet his records weren’t selling as much as his management had hoped. He’d just come off of touring behind The Man Who Sold the World, which had been met with intrigued reviews and a different cover for the American market. Most importantly, it was a make-or-break moment for him. Hunky Dory ended up turning that crisis into opportunity and made what I think is his greatest record.

I have to admit that I once assumed that Bowie’s whole persona was just schtick, all sizzle and no spark. Other than “Space Oddity,” nothing he did ever really hit me. Then when I randomly heard “Queen Bitch” playing at the end of a movie, I didn’t even realize it was Bowie. That crunchy, driving riff grabbed me instantly, and I ran upstairs to frantically Google the odd phrase “bippity boppity hat.” I’ve been a zealous Bowie convert ever since.

There’s just so much going on in this album that it’s hard to know where to begin. There are heartfelt tributes to some of his heroes, like the Velvet Underground-inspired chords in the raucous “Queen Bitch,” the driving “Andy Warhol,” or the earnest “Song for Bob Dylan.” And the ch-ch-ch-changes he’d been going through at the time, such as fatherhood — is there any more delightful song about welcoming a new little one into the world than “Kooks”? — are pushed to the forefront in the lead-off track, which subtly embraces the Buddhist sense of transience and poise amid the strutting, radio-friendly horn section.

Bowie was an extremely literate fellow, with an extensive and tasteful selection of favorite books, so it makes sense that his eloquent and penetrating songwriting really shines through here. And let’s not forget that he’s got a great set of pipes on him, which puts every line across with a conviction and glamor that most other artists can only dream of. That’s what gives his relentless costume-changes their true artistic value; without that powerful voice backing them up, effortlessly leaping from genre to genre, the rest is just smoke and mirrors.

“Quicksand” is a poignant nod to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt, slightly surprising coming from such a flamboyant star in the making. As surreal and genuinely disturbing as “The Bewlay Brothers” is, it becomes slightly more understandable when you consider the fact that Bowie’s brother had been institutionalized, and his family had a history of mental illness. To his immense credit, Bowie found a way to push the boundaries of mental health in an artistically fruitful way and managed to survive his own excesses.

This is why the breathtaking “Life on Mars” is one of Bowie’s essential songs. It’s about a “girl with mousy hair” whose humdrum life on this often disappointingly normal planet can only be remedied by the transcendent power of the imagination, by exploring the endless new worlds offered by art, music, creativity, and desire. The song demonstrated new possibilities by its very existence. What more could be said of any great song?

Maybe that was why so many people were turned on by David Bowie, and why the world mourned him when he died. Bowie’s sound and vision reassured you in no uncertain terms that you weren’t wrong to be weird, flamboyant, or generally unsatisfied with standard issue reality. Bowie provided a brilliant example of what could happen if you explored your own vision a little bit, gave it your best shot, and borrowed liberally from whatever inspired you the most: you might find that everything could be hunky dory, too.

— Matt Hanson

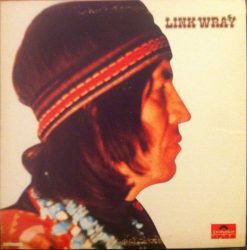

Link Wray: Link Wray (Polydor)

Something special happened when Shawnee Indian guitarist Link Wray went home to his family’s chicken shack in Accokeek, MD, in 1971. Beginning his career in country and rock in the ’50s, he and his brothers Ray and Doug released the hit “Rumble” in 1958. The track’s powerful use of power chords and distortion would become Wray’s signature and legacy. By the ’70s, Wray’s influence could be seen in the likes of Iggy Pop and Bob Dylan. Still, by 1971 Wray and his brothers were running out of steam. So they sought renewal by sweeping the chicken debris out of Wray’s “3-Track Shack” (his primitive home studio on his Maryland farm) shaking cans of nails, and stomping on the floorboards in a lo-fi attempt to recapture some of the sounds of their childhood.

Something special happened when Shawnee Indian guitarist Link Wray went home to his family’s chicken shack in Accokeek, MD, in 1971. Beginning his career in country and rock in the ’50s, he and his brothers Ray and Doug released the hit “Rumble” in 1958. The track’s powerful use of power chords and distortion would become Wray’s signature and legacy. By the ’70s, Wray’s influence could be seen in the likes of Iggy Pop and Bob Dylan. Still, by 1971 Wray and his brothers were running out of steam. So they sought renewal by sweeping the chicken debris out of Wray’s “3-Track Shack” (his primitive home studio on his Maryland farm) shaking cans of nails, and stomping on the floorboards in a lo-fi attempt to recapture some of the sounds of their childhood.

Wray and his brothers would record over a hundred songs in that studio during 1971, teaming up with Steve Verroca, Billy Hodges, and Bobby Howard. Link Wray wallowed in the rudimentary recording equipment; sounds and words were captured as they came out (although Wray and Verroca both share lyrical credit). Notably, Link Wray featured Wray’s vocals — a feat which the one-lunged tuberculosis survivor had to be coaxed into by brother Ray. But what a voice it was! It would be easy to file the album into the roots revival sounds of the time, but Wray’s voice sets it apart with its soul and honesty. It was a voice of lived experience. Wray grew up in rural North Carolina, his family the target of Klan harassment. He learned blues licks from the local elders, playing the old tunes on the porch … or chicken shed, as it were.

Link Wray was recorded at a time America was turning back to its musical roots, but the record was also a very real return for the man himself. The sounds of revival in numbers like “La De Da” ring with an authenticity missing in a hippie festival. “Fire and Brimstone” heralded the apocalypse with a personal and biblical alacrity far beyond any “Bad Moon Rising.” And “Black River Swamp” is a passionate love song for a home treasured in body and soul — it is not a longing for a fantasy. It was more Allman Brothers than Doobie Brothers.

The same session would produce two more albums, Mordicai Jones with pianist Bobby Howard on vocals, and Beans and Fatback, once again featuring Wray’s vocals. The year was astonishingly productive; Link Wray and company found a second ferocious wind to fill their sails. On the last day of the session, however, it is reported that the brother parted ways in awkward silence. Relations soured over finances and other issues. By the end of the ’70s, Wray left the chicken shack behind. He began a retro-rockabilly trajectory guaranteed to capitalize on his earlier ’50s success. The magical moment — with “everybody singing ‘la de da’” — had passed. Proof, perhaps, that sometimes there’s just no going back to the chicken shack.

— Jeremy Ray Jewell

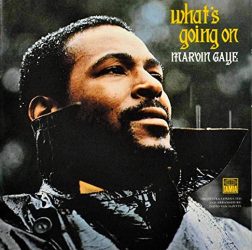

Marvin Gaye: What’s Going On (Tamla)

Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On is a great album. Like Kind of Blue, Sgt. Pepper’s, Dark Side of the Moon, Songs in the Key of Life–level great. I can confidently say it’s the greatest album of 1971, in a year of jaw-dropping excellence in popular music. I won’t say that it’s also the greatest album since 1971, but I wouldn’t want to argue against it. Rolling Stone magazine ranks it the #1 album of all time.

Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On is a great album. Like Kind of Blue, Sgt. Pepper’s, Dark Side of the Moon, Songs in the Key of Life–level great. I can confidently say it’s the greatest album of 1971, in a year of jaw-dropping excellence in popular music. I won’t say that it’s also the greatest album since 1971, but I wouldn’t want to argue against it. Rolling Stone magazine ranks it the #1 album of all time.

The history of this high-water mark in R&B is well documented elsewhere; Ben Edmond’s Marvin Gaye: What’s Going On and the Last Days of the Motown Sound is a good place to start. Like so many other artistic masterpieces, it arose out of a cluster of personal tragedies. Gaye’s marriage had failed (and along with it, relations soured with his father-in-law Berry Gordy, who also happened to be the owner of Gaye’s record label), the IRS was on his tail, and his singing partner Tammi Terrell was diagnosed with a brain tumor. Outside of his personal troubles, the United States was riven by the Vietnam War, Civil Rights protests, the assassination of Martin Luther King, and racially motivated acts of increasing police brutality. Driven by depression and a deepening addiction to cocaine, Gaye attempted suicide in 1969.

In response to all of this darkness, Gaye pulled out of his soul an album of redemptive, ecstatic beauty. Gaye’s loose concept for the record is propelled by the point of view of a Vietnam veteran returning home to a place of injustice, corruption, and ecological decay. Gordy had built Motown records on a sunshiny philosophy of three-minute hit singles that would appeal across racial lines. Protest albums were of no interest. Neither was he interested in a record where songs transitioned into one another as a suite or featured multitracked vocals of Gaye improvising over his own lyrics. “No one wants to hear that Ella Fitzgerald shit,” Gordy reportedly said.

But Gaye took full artistic control, hired an orchestra, worked closely with an outstanding group of studio musicians, and listened intently to his own artistic muse. The result was the best-selling Motown record ever, a triumph of both art-as-commerce and art-over-commerce. There’s something genuinely transcendent about What’s Going On, and you can still hear it today. It’s a revelation to listeners coming to it for the first time now as much as it was when it appeared in May 1971. You may not know, until you give it your full attention, just how deep a groove can go, and why that groove matters. How melody is message. How harmony is unity. How honesty in a human voice needs more than one layer.

Trends and genres come and go, but it’s impossible to imagine a time — in no matter how distant a future — when people are not moved by this music.

— Allen Michie

Tagged: "Mr Big Stuff", "What’s Going On", Allen Michie, Daniel Gewertz, David Bowie, David Daniel, Hunky Dory, Jean Knight, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Link Wray, Marvin Gaye, Matt Hanson, Sticky Fingers

The Rolling Stones cover with the “the bulge of a tumescent organ visible” isn’t passing Facebook’s community standards for obscenity.

I think this is hilarious. It’s great to see the Rolling Stones still being rebellious after 50 years! I know Mick and Keith would be pleased.

Dave Daniel shows how music connects to the times, the politics.

Assume you’ll include Who’s Next, Aqualung, Fillmore East, Cry of Love, and Low Spark.

David Daniel attains profundity in his review of a 50 year-old dance single — Jean Knight’s Mr. Big Stuff — and does it without a whiff of pretension or intellectual wrangling.A perfect merging of review, research, memoir. Of mind and heart.

Coming up online on May 21: an all-star jazz tribute to Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.”

https://www.92y.org/event/marvin-gaye-what-s-going-on-at-50