April Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Music

English Solo Song came along to brighten what I hope are the very last days of a grim winter.

Once in a long while a reviewer can’t stop listening to a CD before sitting down to write about it. For me, this Proud Songsters album demanded to be heard — over a dozen times — and on each occasion I become more appreciative. In fact, my review was late because I became addicted: I couldn’t stop listening. It is as if I had fallen under some the spell of a 20th-century British wizard.

English Solo Song came along to brighten what I hope are the very last days of a grim winter. The 20 songs cheer — and touch one’s soul — as only music (and perhaps chocolate) can. This irresistible compilation features nine singers and a pianist who attended and sang in King’s College in their youth. They have now come together to perform the best of British solo vocal music. The results are dazzling, an exquisitely musical emotional journey. Each of the vocalists is first class and the repertoire is enchanting. In each song, a different voice is highlighted; I particularly adored all three countertenors.

I knew well only one of the singers beforehand, but all have established considerable careers. Gerald Finley, whom I had first gotten to know as Dr. Atomic in John Adams’s opera, sings three songs luminously, including the CD’s only duet,” O lovely night,” with his father-in-law, Sir Christopher Keyte, another former Choral Scholar of King’s College. I learned from the program notes that Finley is an unusually athletic opera and recital star. In 2014, he climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro to raise funds for Help Musicians UK.

Astonishingly, half the tracks on this CD were composed by men younger than 30. Bass-baritone Ashley Riches opens the album with a fine rendition of the elegant “To Gratiana Dancing and Singing,” gracefully accompanied by the terrific pianist Simon Lepper, who plays powerfully throughout. Countertenor Tim Meade contributes an enormously poignant version of one of the most famous folk songs Benjamin Britten ever set, William Butler Yeats’s “The Salley Gardens” ( “I was young and foolish and now I am full to tears”). There are several settings of Shakespeare: Roger Quilter’s “Fear No More the Heat of the Sun” and Iain Bell’s “Feste.” The latter is taken from Bell’s song cycle “These Motley Fools,” which pays homage to four of the Bard’s fools. Countertenor Michael Chance movingly sings, unaccompanied, “My love gave me an apple,” and Finley serves up a passionate performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s rather famous “Silent Noon.” Ruairi Bowen enchants in a delicate version of “I wondered lonely as a cloud,” which was first published as a unison song,

There are well-known 20th-century composers here (Britten, Vaughan Williams, Finzi, Howells, and Rebecca Clarke) as well as contemporary works by Bell, Celia Harper, and Jonathan Dove.

One of the most haunting songs on the album is “King David,” words by Walter de la Mare, music by Herbert Howells. It is sung by countertenor Tim Mead and I cannot imagine a more serene or heartbreaking performance. The eponymous “Proud Songsters,” which is the last song in Vaughan Williams’s collection “Earth and Air and Rain,” receives a lovely performance from Finley.

In a fascinating essay in the album’s program book, Stephen Banfield explains the origins of the music. Wigmore Hall in London has always been at “the acme of English song culture.” (During the pandemic the concert hall served as the precious source of excellent daily concerts, broadcast internationally.) Banfield notes that “a whole generation of song artists actually can be found who all sang in King’s College Chapel Choir.”As for the songs, composers in the past generated income by publishing their music as sheet music. For centuries, reading poetry in Britain was a prized activity and “we can assume that every song on this disc was created because the composer had a volume of poetry (or plays of Shakespeare) open on his desk.” Love was the usual theme; gay love “undoubtedly drove Quilter’s, Britten’s, and Browne’s expressive urge, intimate music that was no doubt an invaluable safety-valve for secrecy in that legally restrictive age.”

— Susan Miron

Plays is Chick Corea’s magnificent final gift to all of us.

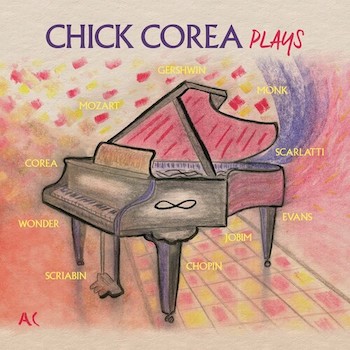

Chick Corea, Plays (Concord Jazz)

This solo piano album was released in September 2020. I’ve returned to it since learning of Chick Corea’s death on February 9, as I’m sure many people have. Now a powerful sense of loss lies between Corea’s crystalline phrases, like the black keys on a piano.

This two-disc CD set collects various recent live solo performances (frustratingly unspecified by place or date). The range of material epitomizes the genre-free essence of late Corea: there is Mozart, Gershwin, Bill Evans, Jobim, Scarlatti, Monk, Chopin, Stevie Wonder, and Corea’s own compositions. All are bristling with the pianist’s bright, clearly articulated touch. Even the ballads sparkle with wit, enthusiasm, and intention.

I’ll just select one section of the program for comment. Corea invites two people up from the audience to improvise their musical portraits. It’s easy to imagine them blushing under the lights while Corea searches their eyes and plays what he sees inside. “Henrietta” is given a graceful, free-flowing waltz, with fragments of melody from a half-remembered show tune. “Chris” is portrayed by a typewriter rhythm and flashes of a Cecil Taylor-like attack up the keyboard.

Then Corea invites two strangers from the audience to share the keyboard with him (tapes rolling for Concord). “Yaron” has clearly studied Corea, and soon it’s impossible to tell them apart. “Charles” and Corea listen to one another carefully, stopping and starting together and pushing one another into freer explorations.

Can you imagine Keith Jarrett doing such a thing, respecting not just the presence of his audience but also the equality of their musicality? Imagine the gift that Corea gave to Henrietta, Chris, Yaron, and Charles. Imagine if it had been you. Plays is a magnificent final gift to all of us.

— Allen Michie

Film

Mostly I Care a Lot is sleek, amoral enjoyment, buoyed by Rosamund Pike’s rakish take on her slimy character.

Rosamund Pike in I Care a Lot. Photo: Seacia Pavao/Netfilx

The writer-director of I Care a Lot, J. Blakeson, provides his greedy, bad-acting protagonist with not a hint of backstory. We can’t rationalize her unconscionable behavior by knowing she was an orphan, or abused by her parents. Marla Grayson (played with glee and abandon by Rosamund Pike, earlier the killer wife in Gone Girl) has no reasons for being so evil except that it appears to be lots of fun, gets the juices flowing, and there’s so much money to be made. Besides, as Grayson tells us up front in voice-over, she’s no different from the rest of us, only better at it: “You think you’re good people? You’re not good people. There’s no such thing as good people.”

Anyway, not in this provocateur Netflix original.

Grayson is a court-appointed legal guardian of elder citizenry, those who need assistance with their well being because of failing health or loss of mental capacity. That sounds vaguely humanitarian but not the way it’s practiced here. Grayson’s clients are uprooted, placed in a senior living facility, need it or not, so she can steal all their assets, put their possessions up for auction, and sell their homes. The ideal clients are ripened “cherries,” those with no living relatives to challenge Grayson as she methodically robs them blind.

Can this awfulness actually happen in America? I Care a Lot flashes some social consciousness, sincere or insincere, through its exposure of a web of corruption in which Grayson spins her scams. She has a doctor friend who, paid off, finds the older people to victimize and declares them in need of a guardian. There’s a court system in which, because Grayson appears so often and cozily before the same judge, she’s trusted to take over a client’s life. Finally, there’s that senior citizen facility filled to the gills with people she has shoved in there. And if a client dies? Grayson shrugs and throws the profile into a trash can. She’s not suffering. She has a wall of photos like a human dartboard of her current elderly prey.

How long can one watch a film in which the main character is so utterly loathsome? The filmmaker, Blakeson, intentionally puts the audience to the test. But, half an hour in, he seems to soften and offer us someone to root for. It’s a sweet old lady, Jennifer Peterson (the great character actress Dianne Wiest), who gets the whole Grayson treatment, landing in a nursing home after being ejected from her Victorian home. It’s repainted to be quickly resold, but not before her Machiavellian guardian has found the key to her safe deposit boss.

But there’s a clever flip in the story. Poor Ms. Peterson suddenly has a malevolent glint in her eye. She warns her guardian: Let me out of the old person’s home…or else! Before you know it, Grayson is a victim herself, chased by the local don of the Russian Mafia (a performance of virtuoso mugging by Peter Dinklage). And guess what? We the audience are manipulated, quite brilliantly, into rooting for Grayson, whom we’d been encouraged to hate, on the run from the mob.

Mostly I Care a Lot is sleek, amoral enjoyment, buoyed by Pike’s rakish take on her slimy character. And there’s one truly great scene: a battle of wits between Grayson and a tanned Mafia lawyer (splendidly played by Chris Messina) hired to buy her off. Too bad the film has to climax with some heavy-handed, obvious comparisons of thievery and capitalism and, really unneeded, a comeuppance conclusion.

— Gerald Peary

Books

The Ever-Changing Past: Why All History Is Revisionist History by James M. Banner, Jr. Yale University Press.

This lively account of historical methodology — particularly the rapid advancement of the ways in which history is complied and created — should appeal to buffs as well as academics who are concerned with evolving information-gathering techniques as well as the dissemination of narratives that explore the past. Particularly interesting to this reader is the writer’s gloss on “new curatorial practices.” Museums are now “placing increasing emphasis on explaining the origins and significance of the works” they have displayed, taking care to present what is “unknown and disputed about them alongside what was known and established.”

Hans Hofmann — Fury: Painting After the War. Edited by Chris Craig. Bastian/Paul Holberton Publishing

Hans Hofmann — Fury: Painting After the War. Edited by Chris Craig. Bastian/Paul Holberton Publishing

Speaking of revisionist history, this slender (45-page) oversize exhibition catalogue reveals an unknown aspect of the art of Hans Hofmann, at least to this observer. Long recognized as an avatar of the American Abstract Expressionist movement, the pictures in this show detail his powerful influence on a broad range of 20th-century artists, including such august names as Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Willem DeKooning. This volume also raises the question of whether British artists such as Francis Bacon looked admiringly at Hofmann.

Minus One — Stories by Doris Iarovici. University of Wisconsin Press

To the roster of world-class Boston fiction writers, including but not limited to Sue Miller, Steve Yarborough, Elinor Lipman, and the under-recognized but great Brendan Halpin, arrives a new entry: Doris Iarovici. The stories in this collection come under the thematic rubric of “loss”; the titular “Minus One” refers to an absent character in each tale. This is a slender collection of ten tales that clocks in at a mere 128 pages, but it nevertheless packs a stunning punch. Iarovici catalogues the awkward and harrowing world of divorcees who return to dating in middle-age, characters who experience what Carl Jung termed “a second puberty.” She gives us a hands-on, bird’s-eye look at what would happen if the family of a psychiatrist faced an insurmountable breach. Iarovici works as a staff psychiatrist at Harvard University and she imbues her fiction with a verisimilitude that is at once deft and forceful.

— Timothy F Barry

Of Human Kindness: What Shakespeare Teaches Us about Empathy by Paula Marantz Cohen. Yale University Press

Liberal academics are a fearful lot, and there is panic in the ivory tower that Shakespeare may become yet another victim of cancel culture, particularly among younger readers who are highly attuned to the injustice of patriarchal power and the plight of the marginalized. So prepare for a wave of testaments to the Bard’s empathetic responses to race, class, gender, and age. Paula Marantz Cohen’s Of Human Kindness is well-meaning, but the effort is earnest to the point of irritation. A Professor of English at Drexel University, she argues that over the course of his playwriting career Shakespeare became increasingly in tune with “the other.” The monochromatic villainy of Richard III gave way to the complex and humane characterizations of Henry V and Hamlet, leading to deep sympathy for the grievances of Shylock, Iago (more on that later), and King Lear. By the time we hit The Winter’s Tale, the Bard’s heart is overflowing with humanity.

Liberal academics are a fearful lot, and there is panic in the ivory tower that Shakespeare may become yet another victim of cancel culture, particularly among younger readers who are highly attuned to the injustice of patriarchal power and the plight of the marginalized. So prepare for a wave of testaments to the Bard’s empathetic responses to race, class, gender, and age. Paula Marantz Cohen’s Of Human Kindness is well-meaning, but the effort is earnest to the point of irritation. A Professor of English at Drexel University, she argues that over the course of his playwriting career Shakespeare became increasingly in tune with “the other.” The monochromatic villainy of Richard III gave way to the complex and humane characterizations of Henry V and Hamlet, leading to deep sympathy for the grievances of Shylock, Iago (more on that later), and King Lear. By the time we hit The Winter’s Tale, the Bard’s heart is overflowing with humanity.

Each era creates its own self-serving version of Shakespeare. A couple of decades ago it was fashionable to cast his plays as guides to honing corporate skills. For instance, Power Plays: Shakespeare’s Lessons in Leadership and Management by John O Whitney and our own Tina Packer of Shakespeare and Company was published in 2001. (No doubt Richard III was a star.) The political pendulum has predictably swung: the Bard’s sympathies are now for the managed. The problem with Cohen’s cookie-cutter is obvious — the accepted chronology of Shakespeare’s plays does not run smooth: his most misanthropic play, Timon of Athens, sits alongside King Lear and Macbeth. Right after Twelfth Night came the ultra-cynical Troilus and Cressida — empathy for a pimp?

Cohen deals, unconvincingly, with her thesis’s inconsistency by examining Measure for Measure. She pokes around, but there’s no humanity in the text. Shakespeare’s play “encourages us to see ourselves in the rigidity, self-righteousness, hypocrisy, sadomasochism, and voyeuristic manipulativeness of its characters.” What happened to the Bard’s evolving fellow-feeling? Well, the troublesome script reflects a “disaffected interlude in Shakespeare’s career.” No, it reflects Shakespeare’s blissfully unruly imagination — all of his plays are mingled yarns, with moments of empathy alternating with visions of inhumanity. In order to flatten Othello into a serviceable homage to the victimized, Cohen insists that Iago does have a motive — he is a disaffected member of the exploited underclass, unfairly passed over for promotion. A byproduct of this intriguing but strained interpretation is to push aside the suffering of Othello and Desdemona. Iago is the kind of character who would fit perfectly into the squalid world of Measure for Measure — but Cohen can’t or won’t see it.

Fatally, Cohen insists that the key to understanding empathy in Shakespeare is to be found in a close reading the texts rather than in viewing stage productions, which over the centuries have only reinforced stereotypical images of Shakespeare’s outsiders (Nazi depictions of Shylock). That’s true, but the opposite also holds — theater performances have helped liberate Shakespeare from prejudice and narrow-mindedness. And it must be pointed out that clear-eyed — rather than rose-colored — dissections of Bard’s texts do not support Cohen’s thesis. For example, Henry V is not as overtly vile as Richard III, but there is evidence he is a war criminal. At two points during the big battle Henry orders the slaughter of the French prisoners (lines that are often cut in performance). No empathy for “the other” here, from the king or those around him. Vengeance in the name of the state justifies murder, even for the Bard. The result of another “disaffected interlude”?

After years as a theater critic, I am highly confident that contemporary stage productions, driven by the sensitive responses of theater artists from the LGBT community and different races, will embrace Shakespeare’s protean imagination by grappling — in illuminating and surprising ways — with their glorious whirligigs of darkness and light. There is no need to be afraid and cling to a stale (and privileged) didacticism, especially in the classroom.

— Bill Marx

Television

A scene from the Russian series, Two Legends.

Let me come back for a bit to Russian television. I’ve already posted positively about The Sniffer. The Sniffer is an investigator who knows the world through his nose, his super powered sense of schmeck. Naturally this gives him an advantage in his vocation as investigator; he can recreate a crime scene with just one sniff: one sniff and he can see it. The downside is the effect of this supersense on his love life. The women he courts get tired of being told that everything they crave to eat is at best inferior if not completely foul.

Now I’d like to mention a show I’ve dug up that I enjoyed when it first appeared on American streaming services — Two Legends. Two beautiful, well-trained secret agents are set loose against enemies and each other. Their legends consist of the roles they play, he as a teacher of mathematics, she, as, well, I don’t quite remember. I do remember that the best lesson she delivers is to this wise guy kid: she does it by shedding her legend and appearing dressed to the max as the irresistible female, or if you prefer dominatrix, which she is. She warns the kid: keep it up and you’ll have to deal with me. Yes it’s all style but since that is all it is, the style is very good.

If you liked The Matrix and its style you’ll like this, and want more of it.

— Harvey Blume

Tagged: Allen Michie, Bill-Marx, Chick Corea, Gerald Peary, Harvey Blume, I Care A Lot, Plays, Proud Songsters, Susan Miron, Tim Barry