Book Review: “The Making of the American Creative Class” — Unions, Their Rise and Fall

By Steve Provizer

This history of union activity among white-collar workers in New York City tells an illuminating story about creative labor’s effort to be treated with respect by the powerful.

The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Culture Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism by Shannan Clark. Oxford University Press, 608 pages. $34.95.

Buy at Bookshop

How does the reader know right off the bat that The Making of the American Creative Class means business? It starts off with a three-page list of organizations and their acronyms. The book covers an epoch economists often call “Fordism” — from the 1910s through the 1970s. Author Shannan Clark argues that it was an era in which capitalism invested in technologies that produced durable consumer goods and generated the consumer demand necessary to keep these investments profitable. I wouldn’t call it capitalism’s heyday — more like the period when America got itself ready for neoliberalism to swoop in. During this period of intense labor and political activism, many of the levers of power were up for grabs. Unfortunately, for about 50 years, it’s clear who ended up controlling the machinery.

The book’s title, The Making of the American Creative Class, is slightly deceptive. The author’s major focus is on union activity among white-collar workers in New York City. Does this constitute a “creative class?” Clark concentrates on newspapers, magazines, advertisers, and radio and TV networks, but he defines the term broadly: it includes writers, illustrators, layout artists, photographers, printers, secretaries, shipping clerks, bookkeepers, engineers, fine artists, architects, physicians, teachers, and nurses.

The aim of the white-collar union movement was to turn a relatively privileged social group of proprietors and independent professionals into a group of salaried employees. Instead of raising the status of a particular segment of workers in a shop — say writers or engineers — the status of all the firm’s employees were considered altogether. It was a strategy that could only work in an environment that encouraged solidarity.

It’s hard to imagine a majority or even a small subset of those who lived through the Great Depression wanting to relive it. But the shared misery of the catastrophe united many Americans, who believed that they were helping to revive their country by shaping its political and artistic cultures. The result was a short-term seismic shift toward more equal distribution of income and wealth across class lines. Despite the reduced circumstances of many of the book’s protagonists, Clark describes them taking political/cultural agency in a way that I find thrilling.

I don’t think many of us realize the inroads that unionism made into the workplace. How many of us know that the animators at Fleischer Studios, who made the Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons, struck successfully in 1937, winning union recognition and significant pay raises? Unfortunately, in response the owners moved their operations to Florida the following year. United American Artists UAA Local 60 was able to win severance payments for its members at the studio, but it could not prevent the flight of 250 jobs. We are given a number of the back and forth scuffles between labor and capital, a healthy conflict that was most intense from the ’30s to the ‘5os, though the clashes continued, to some degree, into the ’70s.

Another refreshing aspect of this book; it elucidates the large role played by women in labor’s struggle. Many females analyzed the reasons behind their oppression, proving the ways that hostility against their gender insinuated itself into the culture. They advocated programs that paved the pathway for women’s autonomy. This important manifestation of feminism took place between the suffrage struggles of the early 20th century and the “second-wave” feminism of the ’60s and ’70s.

Of course, there was acrimony among organizing efforts, increasingly sparked by the word “communism,” but until the late ’30s, the effort to combat the Great Depression generated a synergy between activists and governmental efforts. Left-wing political energy inspired the creation of a number of organizations in FDR’s New Deal. Unemployed creative, professional, and technical workers joined with militant white-collar unions, the John Reed Communist Clubs, and other radical collectives of artists, writers, and performers to push for a massive expansion of government patronage of arts and culture. The results — the Federal Art Project, the Federal Theater Project, the Federal Music Project, and the Federal Writers Project — were unprecedented in how they persuaded the nation that the production of culture was a public good.

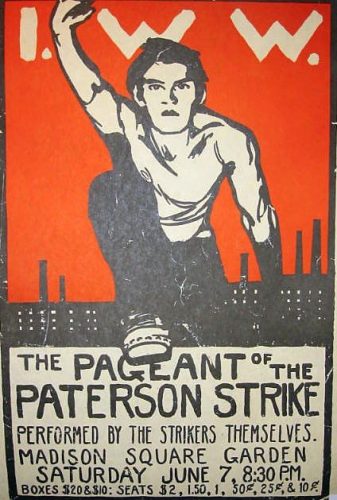

It was a time when there was a fairly widespread vision that artists and workers had much to say to each other. Educational programs dedicated to reaching across classes helped to strengthen the association between modernist aesthetics and “radical” white-collar unions. A Culture and the Crisis manifesto pointedly asked in the early ’30s: “Why should intellectual workers be loyal to the ruling class which frustrates them, stultifies them, patronizes them, makes their work ridiculous, and now starves them?” Eggheads faced a stark choice of “serving either as the cultural lieutenants of the capitalist class or as allies and fellow travelers of the working class.” There were seven art locals affiliated with larger unions in NYC. Painter John Sloan designed the set for the Industrial Workers of the World’s Paterson Strike Pageant at Madison Square Garden. Lewis Hines created a series of stunning photo-montages for a poster campaign by the National Child Labor Committee.

Many of the organizations explored how capital should be mobilized, given the increasing centralization in the production of mass culture. Radio programs were branding platforms, often for the sponsorship of a single advertiser; the routines of popular broadcast entertainers and advertising jingles became the lingua franca. As someone who can still sing the “Good and Plenty” candy jingle, I can vouch for the longevity of this approach.

Many of the organizations explored how capital should be mobilized, given the increasing centralization in the production of mass culture. Radio programs were branding platforms, often for the sponsorship of a single advertiser; the routines of popular broadcast entertainers and advertising jingles became the lingua franca. As someone who can still sing the “Good and Plenty” candy jingle, I can vouch for the longevity of this approach.

The accumulation of data on readership and listenership that started in the early ’30s is, of course, much with us today. And it spoke to the question of whether or not America would remain, as sociologist C. Wright Mills put it, “a great sales room, a network of public rackets, and a continuous fashion show” in which “the image of beauty itself ” was “identified with the designer’s speed-up and debasement of imagination, taste, and sensibility.” Or would the public reject “conspicuous consumption” and planned obsolescence? To this end, there were efforts to convince people that consumption should be seen as a political act: buying what American unions made was a patriotic act. This movement achieved mass attention through the creation of such publications as Consumers Union Reports, PM, In Fact, and Friday.

Consumer Union Reports, aside from product testing and ratings, encouraged Americans to purchase union-made goods, participate in consumer cooperatives, harbor deep skepticism toward advertising claims, use evaluated or generic goods instead of branded goods whenever possible, and demanded an increase in the public provisioning of goods and services. CUR lobbied for new regulatory initiatives, the most important of which was the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938, which expanded the powers of the FDA. In one revealing example of the intermingling of the arts and consumer politics, Consumer Union Reports accompanied one of its used car reviews with an excerpt from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath in which native Okies were fleeced by unscrupulous auto dealers.

In 1939, Hearst and company developed a report on Communist ties at the Consumer Union that was accepted whole hog by the House Special Committee Investigating Un-American Activities. The material was distributed to hundreds of newspapers, many of which printed it; not only was it from the government, but it enjoyed the immunity of Congressional testimony. The document could be quoted from without fear of libel charges. This strategy became the spearhead for “a new alignment of anticommunist enterprises, institutions, and personalities that spent the next twenty years working to eliminate the influence of progressives and radicals from the culture industries.” Consumer Union survived the early Cold War years by narrowing its political aspirations and adjusting its consumer guidance. Consumer Reports survived but it now only rates products. By the way, Hearst tried to piggyback on this movement with the consumer scam known as the “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.”

Author Shannan Clark.

Tactics used to curtail union activity were many, including hiring anti-labor law firms and private detective agencies, such as Pinkerton and Burns, to spy on workers. Union activists were sometimes beaten up. Media enterprises collaborated with prominent advertisers to distort coverage of labor activism, as when several New York City newspapers smeared the CIO retail and distributive union during its 1941 strike against Gimbels department store. Of course, as World War II ended and the Cold War heated up, red-baiting became the inevitable fallback for weakening the power of unions.

Midterm gains in 1942 elections by Republicans also encouraged undercutting of the pro-union movement. Strikes were suspended and private businesses dominated wartime government work. During the war, the Advertising Guild and Advertising Mobilization Committee (AMC) produced materials that encouraged compliance with price control, rent control, rationing, and other elements of wartime social consumerism. But the Ad Council, which represented mainstream advertising agencies that were paid by large corporations, maintained the biggest bullhorn when it came to propaganda for the free market. In 1944, many unions came together to form the People’s Radio Foundation (PRF) for the purpose of getting an FM license. HUAC shared PRF files with the FCC and, because of the Communist taint, the application for a license was rejected in 1947.

Much of HUAC’s energy went into investigations of radicalism in the labor movement and in media and entertainment. Other Congressional committees were formed as reinforcements in this effort. Pro-communist affinities were considered tantamount to participation in a criminal conspiracy, not a form of political expression protected by the First Amendment. An array of political committees, civic groups, and grassroots organizations propagated and reinforced the anti-union efforts of government figures and professional anticommunists.

The Popular Front fought back, creating Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). It launched the Voice of Freedom Committee (VOF), chaired by writer Dorothy Parker, to fight for the restoration of progressive perspectives on the public airwaves.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) did not serve as a helpful recourse. It was hampered by a lack of funding and political clout. There were extensive delays in meting out penalties, which were often only slaps on the wrists of offenders. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act reduced the effectiveness of the NLRB even further by restricting union activities, throwing more control to corporations, and insisting that unions swear that their leadership wasn’t Communist-affiliated. Throughout the ’30s and ’40s, laborcentric interests and publications intermingled freely with Communist-oriented groups. A lot of top union leadership used to have — or still had — some Communist affiliation. These people had to be purged by unions if they wanted to maintain their rights to collective bargaining. The Congress of Industrial organizations (CIO) was forced to purge itself of “Communist-tainted” unions.

Still, there were solid postwar gains by white-collar unions, and while arts guilds weakened during the war, unionization increased in the movie and radio industries, including film processing technicians, publicists, and script writers. The Newspaper Guild also grew stronger. That vigor did not last. The Making of the American Creative Class gives a lot of coverage to the long-term struggle of the Newspaper Guild against Henry Luce and his Time magazine empire, the machinations of lowest common denominator media mogul Rupert Murdoch (New York Post, etc.), and the New Yorker magazine’s William Shawn. All of these confrontations ended in the Guild’s defeat or token concessions by the anti-union publishers.

Hostile Senate committees continued through the ’50s and, as unionism lost political clout, so did the muscle behind its promotion of a class-conscious perspective on white collar labor as well as its advocacy of social consumerism. Competitive individualism (the grand adventure of entrepreneurship) replaced the earlier ethic of solidarity. Organized labor increasingly shared employers’ commitment to the free market as well as to unfettered and unregulated markets. Workers (or at least their leadership) accepted that patriotic fulfillment was best found when they acted as competitive individuals in the marketplace. Consumerism was the American way.

In the advertising world of the late ’60s, a young group of writers and artists embraced the idea of advertisements as works of popular art. They could be more than sales pitches. (Andy Warhol’s fame was a graphic representation that popular art could convey dissent.) There was excited talk among unions of using advertising as a way to get the word out about workers’ concerns — the power of PSAs and “protest” posters. Of course, large PR firms absorbed these strategies in order to uphold the prominence of consumerism and individuality. As these agencies “went public” and/or were swallowed up by large corporations — as were many publishers — fealty to stockholders became the overriding directive. As the ’70s arrived, what had once been a lively battle in mainstream culture was all but over: designers who saw their work as contributing to a vision of social democracy had been displaced by those who saw it as a marker of cultural sophistication or a gateway to consumerism.

Most motion picture unions folded, although the Screen Publicists Guild (SPG) continued until the ’70s, when outsourcing and relocation did it in. Meanwhile, publishing jobs contracted throughout the ’70s — many magazines and newspapers were shuttered.

The women’s movement had a great impact on the Newspaper Guild, culminating in Betsy Wade and her slate taking over the Guild in 1978. However, there was a backlash against her using resources to fight race and gender discrimination and Wade’s slate lost a special election in 1980. In one small victory, a group called Women in TV used FCC guidelines to report inequality. They challenged WABC’s license and the FCC temporarily withheld it, forcing the station to negotiate.

The mid-’70s continued the slide of the labor movement, with unemployment, inflation, the gas shortage, Watergate, surging levels of inequality, and the decline of the GDP. With the Reagan era came the final harsh blows: withdrawal of federal support for cities, tax cuts for the rich, and punitive measures for unions.

Acquisitions and restructuring of firms led to big layoffs, enhanced by the promotion of “blockbusters” with an increasing emphasis on quick returns. Discontent over declining conditions led to the chartering in 1983 of the National Writers Union (NWU), which hasn’t nearly the kind of clout the Newspaper Guild once did.

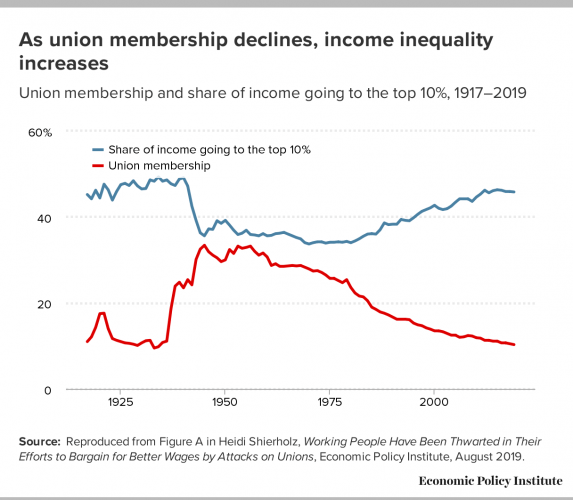

The percentage of workers belonging to a union in the United States peaked in 1954 at almost 35 percent — more than one-third of American workers. The percentage now is about 10 percent. The percentage of wealth owned by the richest Americans actually declined during the middle ’40s and remained stable for the next 35 years. We know what’s happened since then.

Although The Making of the American Creative Class is dense with the comings and goings of unions, guilds, and businesses, the author’s writing style is lucid. You may have to read a page more than once to get the characters and their actions straight, but that’s not because Clark hasn’t laid out the proceedings with admirable clarity — these are complex stories and he tells them in detail. Of course, the struggle of creative workers over many decades defies a comprehensive summary, even in a book of this length. Still, this volume examines, in depth, a vital part of history that isn’t taught much in schools or noticed in our popular media.

Ours is a time where guilds and unions that once protected workers of all types have largely been replaced by the onerous “gig economy,” in which workers have no collective leverage to use against exploitative employers who, empowered by technology, resist offering “luxuries,” like health coverage, salary raises, paid vacations, and child-care options. (The explosion of online sales made possible by computers and the internet has profited Silicon Valley, not writers or publishers.) This history of the rise and fall of unions tells an illuminating story about creative labor’s effort to be treated with respect by the powerful. It ends happily for the 1 percent — less so for the rest of us.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

I remember David Quaid, a groundbreaking cinematographer based in NYC, telling me about being run off the road in Westchester County by people who he thought were part of the group of “Communists” trying to take over the local film trades union. The tension and often open warfare between trade unionists and the American Communist Party labor organizers was endemic from the 1917 Revolution and is probably still ongoing. It split the Socialist Party and hampered labor organizing not only in white collar trades but blue collar ones as well as the civil rights movement.

A divisive, unfortunate, but understandable conflict of goals, although more difficult to understand after the Russian-Nazi pact and the various Stalin trials. I remember the strife among lefties in the 1960’s around whether you identified yourself as a Trotskyite, a Leninist or an Anarchist. And whether you thought Mao’s Cultural Revolution was a good thing.

Another unfortunate feature of our human personalities is that many of us tend to “look down our noses” at people we consider less clever than we are. And this holds true, also, for people whom we don’t know except by what job they do. When I was a member of the Newspaper Guild back in the ’60s I remember conversations in which writers (I was one) would be amused by the fact that the Guild represented not just the “creative” workers at papers and magazines, but also secretaries, ad salespeople, and all sorts of other people without whom the paper couldn’t have succeeded, but whom many snooty “creatives” felt superior to. Now obviously if one is thinking clearly, one recognizes that if you want to have a successful union, it had better represent all the people who work for wages in a business, and that they had betterhave a sense of solidarity . But who thinks clearly?

The employers, needless to say, were brilliant at finding these little rifts between workers, and widening them in any way possible.

Thanks for your comment, Larry. I think mutually-felt economic pressures created a sense of solidarity among “creatives” and other workers until the 1950’s. With the recovering economy, it wasn’t difficult for owners to exploit the fissures that opened up.