Opera Preview: Boston Lyric Opera Revamps Philip Glass’s “Fall of the House of Usher” for Today

By Ralph P. Locke

How do you make filmed opera relevant in the Age of COVID? The BLO isolated the performers from one another and made E.A. Poe’s story the dream of an immigrant child in detention on the US/Mexico border.

William and Roderick carrying a coffin in the Boston Lyric Opera film version of The Fall of the House of Usher.

Boston Lyric Opera will begin streaming online its newly reimagined production of Philip Glass’s 1987 opera, The Fall of the House of Usher, on January 29. Exclusively on BLO’s operabox.tv.

Question 1: How do opera companies keep alive, and keep paying singers and instrumentalists, in an age of social isolation?

Question 2: How can an opera based on an Edgar Allan Poe tale from nearly two centuries ago (1839!) possibly speak to the challenges facing America and the world today?

Boston Lyric Opera is proposing answers to both of those questions with its upcoming streamed film of the 1987 opera The Fall of the House of Usher. The opera was composed by Philip Glass to a libretto by noted children’s book author and radio-drama advocate Arthur Yorinks. Usher was first performed in 1988 by American Repertory Theater (Cambridge, MA).

(The work should not be confused with other operatic adaptations of Poe’s story by Debussy, Gordon Getty, and progressive-rock musician Peter Hammill.)

It might seem an impossible task to film an opera during the Age of COVID without putting the performers at risk of spreading the virus.

But a public statement recently sent out by Boston Lyric Opera explains how the seemingly impossible was, in this case, perfectly doable:

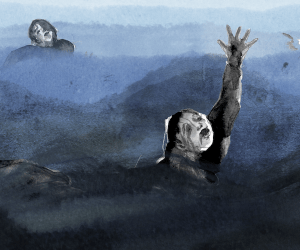

Luna struggles to cross the river in the BLO film version of The Fall of the House of Usher.

“Music Director David Angus, who monitored the session remotely from his main home in England, said Glass’s precise compositions made it possible for orchestra members to follow a click-track for timing instead of relying solely on a live conductor. Singers recorded their parts in separate sessions, listening to the recorded score.”

Presumably such a method of recording an opera piecemeal, in many different locations at different times, would be frustrating or worse with some other kinds of operas. But Glass’s music — here as in many of his pieces — often maintains a consistent basic pulse over long stretches (while of course varying the surface rhythms and the pitch content in the various vocal and instrumental parts).

So much for “merely” technical considerations.

The creative team for this production also decided to try to make this opera speak directly to sociopolitical issues that have been roiling the North and Central American scene for the past several years.

The novella and the 1988 opera deal with a brother and sister mysteriously holed up in a vast old house and suffering and apparently dying of causes left unspoken (disease? mold in the house? guilt over incest?). For the opera, librettist Yorinks has given the brother, Roderick, words to sing but has the sister, Madeline, sing wordlessly. He has also given a name, William, to Roderick’s friend, who may or may not be romantically/sexually involved with either (or both?) of the siblings — or merely trying, desperately, to help in a situation filled with doom and dread.

For the BLO’s streamed film, this Poe-derived plot is nestled within a new story, worked up by Spanish screenwriter Raúl Santos. Now the Ushers’ cursed mansion and its inhabitants “are fantastical figments in the imagination of Luna, a mute immigrant child held in a detention facility at the border between the United States and Mexico.” The film’s director is James Darrah, who produced Soldier Songs, a current online project by Opera Philadelphia.

Since its 1988 staging in Cambridge, Glass’s opera has been mounted by numerous opera companies, including Long Beach Opera (California), Wolf Trap Opera (Virginia), Cottbus (Germany), and the renowned Maggio Musicale Festival in Florence (Italy).

Luna is restrained in a scene from the BLO’s film version of The Fall of the House of Usher.

The Boston Lyric Opera production involves singers and instrumentalists, of course, but also animation, stop-action filmmaking, an empty dollhouse, archival documentary footage, and much more. The main vocal parts are taken by Chelsea Basler (Madeline), Jesse Darden (Roderick), and Daniel Belcher (William). All are acclaimed artists with much stage experience. Daniel Belcher, for example, is a renowned exponent — in opera houses around the world — of such varied and dramatically demanding roles as Mozart’s Papageno, Rossini’s Figaro, Gounod’s Mercutio, and John Corigliano’s Beaumarchais.

The visual-production team includes Yuki Izumihara (production designer), Pablo Santiago (director of photography), Camille Assaf (costume and doll designer), Yee Eun Nam (art director/lead designer), Will Kim (lead animator), Jian Lee (associate animator), and Rodrigo Muñez (lead illustrator).

If you want to get an advance taste of the music and of Yorinks’s libretto, a complete recording (from Wolf Trap Opera) is available on Spotify and other streaming services. Individual scenes can be heard or viewed for free (some sung in English, others in German) on YouTube. Superstar countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo’s recording of one aria (“How All Living Things Breathe”) was used for an imaginative video available here.

But I know I’ll be watching this newly reconceived and timely version, starting January 29, online. And thinking about the multiple questions and issues that it boldly raises.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Boston-Lyric-Opera, Fall of the House of Usher