Book Review: “World of Wonders” — A Natural Counter to the Chaos of Our Political Moment

By Patrick Conway

These essays aren’t overly scientific; instead, they remind us, with a gentle nudge, to take delight in nature, to pay attention to it, to be observant.

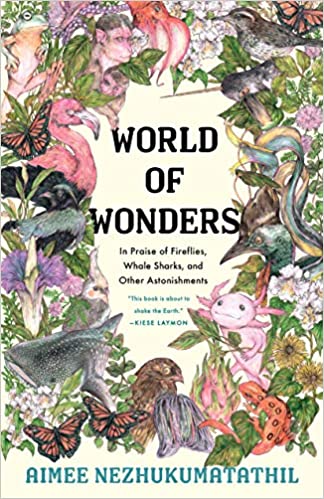

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Illustrated by Fumi Nakamura. Milkweed Editions, 184 pages, $25.

Buy at Bookshop

David Foster Wallace told us to consider the lobster. Aimee Nezhukumatathil would have us go much further. Consider the firefly, the peacock, the vampire squid, and before you’re done, consider the firefly again. And why stop at the animal kingdom? Consider the catalpa tree, the dragon fruit, and that most cautious and sensitive of plants, the touch-me-not. In her new book, and her first book of prose, World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments, Nezhukumatathil weaves together a collection of essays that touch on issues of family, travel, and identity. What holds the collection together is a focus on the quietly miraculous ways in which the natural world inspires wonder. The essays aren’t heavily scientific; instead, with a gentle nudge, they remind us to take delight in nature, to pay attention to it, to be observant. Contributing to the collection’s charms are illustrator Fumi Nakamura’s depictions of the volume’s animals, plants, and trees.

I’ve found myself increasingly drawn to writing that doesn’t tell readers what to think, but offers opportunities to consider the world from new perspectives. There is no shortage of news stories, opinion pieces, and social media posts begging for our attention: the recent insurrection at the US Capitol, rumors of more violence to come, a virus still running rampant within our communities, and a disgracefully slow vaccine rollout. Staying informed is warranted, of course, but not to the point of compulsion. Taking in waves of information and misinformation, opinions and outrage can become addictive, especially now, at a time of quarantine and stay-at-home orders. With the nimbleness of a poet’s touch, Nezhukumatathil’s essays emphasize the importance of not allowing other aspects of our lives — and perhaps more centrally important aspects — to go ignored.

Each essay, short and often relatively simple, is narrated through the lens of the author’s life, deftly exploring the ways in which, if we try, our lives could intertwine with the natural world around us. Nezhukumatathil interlaces stories of her upbringing and family life with her first forays into becoming a poet and her travails within academia. Her family moves about the country during her childhood; after that, she navigates graduate school, works in academic positions, and travels to locations around the globe in the enviable position of a “visiting writer.” She repeatedly turns to nature to reflect, to find solace, to seek inspiration, and to ground herself. One essay examines the ways a catalpa tree can summon up memories of childhood, another how the colorful array of a peacock’s plumage conjures ancestral ties. There are a few larger species discussed — the whale shark, octopus, and corpse flower among them — but most of the subjects here are animals and plants that often go unnoticed: the cactus wren, the ribbon eel, the red-spotted newt, the axolotl. Nature, both in its grandest and simplest forms, offers a way to better understand ourselves and our communities.

There are certain essays that introduce complex themes, such as when the author as a child — a self-described “brown girl” — is insulted and made to feel an outsider by some of her white classmates, or when she reflects on the power dynamics latent within the process of tenure review, or when she briefly considers the troubling effects of climate change. But Nezhukumatathil does not dig too deeply or linger too long on any of these difficult issues. As important as they may be, they are not her central focus. Instead, World of Wonders is largely a celebration of the joy found in nature, suggesting that the preciousness of existence can be a starting point for finding meaning and a sense of belonging. The book is an argument for the elemental value of taking pleasure in the natural world, of all of us appreciating the wonder of both flora and fauna.

The danger, of course, is that the slenderness of Nezhukumatathil’s essays will prevent the book’s central message from being taken as seriously as it should. Who will believe, for instance, that anything about the potoo or the dancing frog is of significance when our democratic institutions are under attack? Why pay attention to that creature when the threads of social cohesion are fraying? Why stop and consider the flamingo? In this sense, World of Wonders can be cursorily dismissed as an escape from the chaos in our political climate. But it shouldn’t be. In the simplicity of Nezhukumatathil’s book lies its power. She encourages us to establish a familiar relationship with nature; to cherish it as a refuge where we can lose ourselves (even if momentarily). She doesn’t scold her readers, but instead asks tender questions: when was the last time you cut a rug like some superb bird of paradise? Or stopped to notice the difference between an oak leaf and a maple leaf? Or tried to catch a firefly on a summer’s evening to admire its glow? The answers to those questions may have more to do with healing our fractured culture than we think.

Patrick Conway is a former criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, DC, and Boston, and a current doctoral candidate at Boston College researching the expansion of higher education opportunities in prison. His writing has received recognition from the Best American Essays anthology, and an article of his on the involvement of higher education in prison was just released in an issue of the Harvard Educational Review. When not writing on crime or education, he writes on nature. He can be reached on Twitter @PFConway30.