Visual Arts Commentary: An Enduring New England Design Influence — The Shaker Style

By Mark Favermann

As we move into the 21st century, with the climate crisis and consumerism on the rise, the Shakers’ “less is so much more” sensibility takes on even more significance, practical as well as spiritual.

Red Shaker Box, Source: Enfield Shaker Museum, Enfield, NH.

During a time when we are hunkered down in our various dwellings, spending an excessive amount of personal time on our phones, computers, and television screens, we can’t help but start to look carefully at our immediate surroundings. We begin to evaluate where we live, particularly our furnishings and accessories. Today, most of our furniture and fittings have been influenced by modern design trends, but these are the fruits of the past, the result of various historic influences. One of the most fascinating is a homegrown New England tradition: the Shaker style of the 19th century.

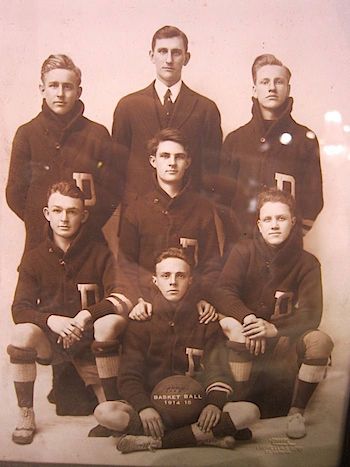

Here is a concrete example of Shaker influence, though the story is a “rural myth” that is somewhat true. At the very least it is a good yarn (pun intended). During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a few Dartmouth College football players noticed the cardigan sweaters that the Shaker men of the Enfield Shaker Village were wearing as they planted or harvested crops a few times a year on their 2000-acre farm near Hanover, NH. Like other handcrafted items by the sect, the knitted garments the collegians admired were simple but elegantly functional.

The undergraduates asked the Shaker sisters if they could have sweaters made for them in what became to be known as Dartmouth green. The garments were made. A few weeks later, after playing Harvard, members of the Cambridge team asked if they could get sweaters made in crimson. The sisters obliged. Of course, Yale also fell for the sweaters and requested blue ones. Thus, the now ubiquitous varsity letter sweater was born — a sports staple created by the Shakers.

1914-15 Dartmouth Basketball team with sweaters, Source: Dartmouth Athletics Archives.

True or not, the story effectively shows how deeply Shaker design has influenced the way our furniture and, surprisingly, our clothing looks. With its commitment to excellence and quality materials, the Shakers’ finely crafted brand of functional minimalism set a high aesthetic standard for emerging design style products. The Shaker style eventually became an accepted part of American and European furniture design. The catalogues of retailers like Wayfair, Crate and Barrel, West Elm, and even Design Within Reach and IKEA, list Shaker-influenced designs. Shaker design has inspired such notable and diverse creators as George Nakashima, Hank Gilpin, Roy McMakin, Thomas Moser, and Charles and Ray Eames, as well as a number of other Scandinavian furniture-makers.

The Shaker movement in America was born in 1776 when Mother Ann Lee emigrated from Manchester, England, with a small group of followers. The Shakers flourished in the America of the early 19th century. By 1840 there were four to six thousand members living in 18 principal communities, from Maine to Kentucky, with over a third of them in New England. Isolating themselves from society, they lived in large “families” that were both celibate and communal. The sect got its name from perceptions of their group dancing — their “shaking” movements were celebrations of their deep Christian faith. As they attempted to establish heaven on earth, they created a visual environment of such harmony and quiet power that it continues to wield considerable power today. New technologies were embraced by members of the sect, so their simple, minimal designs were fashioned with the assistance of the most up-to-date tools and techniques.

Several Shaker villages and museums can be found in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, with a pair in New York State. There are two magnificently restored Shaker villages, one in Canterbury, NH, and the other in Hancock, MA. Educational museums can be found in Alfred, ME, Enfield, NH, and Fruitlands, MA. Other villages can be found in Sabbathday Lake, ME, and Shirley, MA. All of these locations are worth a visit, an invaluable opportunity to experience, up close, the grace of the Shakers’ architecture and functional objects.

A product of the 18th-century working class, the Shakers’ Christian belief system embraced hard work and shared community. It also espoused freeing oneself from excessive material wants and wanton sensual desires. This rebellion against the tyranny of things resulted in a design style that can be considered an early — but refined — form of minimalism. Shaker design has a decidedly more natural connection with its materials, more Nordic than English.

Functional Shake Furniture, Source: Invaluable America Auction Elements.

For the Shakers, function was the primary consideration in all aspects of design. Furniture was inevitably straightforward, with emphasis on clean lines. Ostentatious ornamentation was rejected; there are few embellishments other than slight decorative flourishes in a piece’s elegantly turned legs or some small, detailed carvings. At their most decorative, the latter often subtly depict natural forms — leaves or acorns. The Shakers’ commitment to the unadorned shaped their interiors, which included plenty of negative space. Few accessories, other than highly functional ones like serving bowls, brooms, and candles, were considered essential.

The Shakers’ color palette favored natural hues. Shaker interiors preferred more muted tones: tans, grays, off-whites, etc. However, occasionally a colored focal point, like a painted oval box or natural flowers, would command the eye and humanize a space. Also, furniture would often be painted or stained a deep red, brown, or even blue.

Of course, the most common Shaker design elements — found in chairs, cases of drawers, work stands, baskets, oval boxes, wheelbarrows, stoves, looms, and even tailoring tools — have a purity of form that transcends mere utility.

And this marriage of visual finesse and pragmatic purpose has a number of cross-culture resonances, particularly with the poise of traditional Japanese design. This similarity was explored with existential adroitness by the Art Complex Museum at Duxbury, MA, in its 1996 exhibition Kindred Spirits: The Eloquence of Function in American Shaker and Japanese Arts of Daily Life. This exhibit drew an illuminating connection between the shapes inspired by Japan’s Zen sensibility (the sound of “one hand clapping’) and the rhythmic cadences of the stomping feet of American Shakers.

In our Amazon Prime age of more things, there are those who call themselves “minimalists.” Their notion is to break away from what they see as our slavery to capitalism, to cast materialism aside. The Shakers of the 19th century would smile with recognition. As we further move into the 21st century, with the climate crisis, environmental concerns, and consumerism on the rise, the Shakers’ “less is so much more” sensibility takes on even more significance, ranging from the practical to the spiritual.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.