Book Review: “This Isn’t Happening: Radiohead’s “Kid A”” — An Enduring Soundtrack for our Malaise

By Matt Hanson

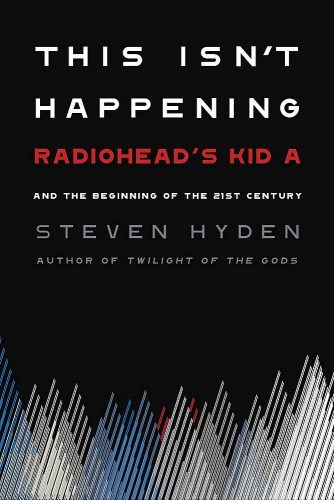

Steven Hyden’s This Isn’t Happening, a book-length appreciation of Radiohead and Kid A is one of the best books I read all year.

This Isn’t Happening: Radiohead’s “Kid A” and the Beginning of the 21st Century by Steven Hyden. Hachette Books, 256 pages, $27.

Buy at Bookshop

Once, many years ago, I made the tragic mistake of not bringing my CDs with me on a road trip with the family. All was not lost; I did have my discman. The best I could do was to borrow what one of my siblings brought, which was one of those Now That’s What I Call Music compilations, chock full of the usual sugar-rush pop stuff (Jennifer Lopez, Backstreet Boys, etc.) which was fun I guess but wasn’t going to sustain me for very long. Oddly enough, it also had a Radiohead song that stood out like a Bosch painting amid all the glimmering pop tunes.

Once, many years ago, I made the tragic mistake of not bringing my CDs with me on a road trip with the family. All was not lost; I did have my discman. The best I could do was to borrow what one of my siblings brought, which was one of those Now That’s What I Call Music compilations, chock full of the usual sugar-rush pop stuff (Jennifer Lopez, Backstreet Boys, etc.) which was fun I guess but wasn’t going to sustain me for very long. Oddly enough, it also had a Radiohead song that stood out like a Bosch painting amid all the glimmering pop tunes.

Somewhat ironically entitled “Optimistic” it featured a doomy, ominous rhythm and a plaintive vocal from Thom Yorke (whose aching, operatic falsetto could make you cry while reciting a takeout menu) about flies buzzing around his head, strange creatures emerging from swamps, intoning that “the big fish eat the little ones” and leavening that malaise with the almost pleading chorus, “you can try the best you can/ you can try the best you can/ the best you can is good enough.”

Back at the beginning of the 21st Century, when that song first came out, Radiohead was at the top of their game and at the end of their rope. Having come up in the alternative-friendly ‘90s with instantly anthemic but rigorously self- critical songs like “Creep” and “Fake Plastic Trees,” Radiohead had made a name for themselves in the States — the group had filled their boots, as some of their fellow Brits might put it. But Radiohead was acutely aware of — and philosophically interested in — the tech-saturated, hyper self-conscious, anemic postmodern world. And songs that probed contemporary dehumanization did not fill stadiums.

The very private Thom Yorke was strung out from the road and the grotesqueries of fame. At one point he spontaneously tried to escape from one of those stadiums and seemed to succeed. Only to wind up finding himself on a train chockablock with hyped up Radiohead fans who were cheerfully heading to the very same stadium he thought he’d broken out of. You couldn’t ask for a better metaphor for the perils of being one of the biggest bands in the world. Every band who got there at some point in their careers — The Beatles, the Stones, Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, The Police, R.E.M., Nirvana, OutKast, and many more — all dealt with the fame monster in their own ways, which usually mean going crazy for a few years or completely falling apart.

Kid A, the record that resulted from months of creative frustration, was a watershed moment for Radiohead as a band interested in taking their sound farther out, right into the ambient unease of the zeitgeist. Earlier this year, music critic Steven Hyden’s published This Isn’t Happening, a book-length appreciation of Radiohead and Kid A — and it is one of the best books I read all year. Hyden rigorously parses out the kind of details music geeks demand, such as how the songs were constructed. Which is great if that’s your thing, as it should be. But Hyden goes further, engagingly exploring how Kid A distilled so much of the postmodern dread, anxiety, and paranoia that we all now take for granted as our lot.

To illustrate this point, Hyden mentions a contemporaneous interview with Stephen Colbert, where the witty host follows up some silly questions with a more pointed query, as is his want: “For decades, you’ve been writing music that is uneasy and anxious with regards to society, our government, technology, the general direction of the world…How does it feel to be right?” The studio audience, of course, ate it up.

There’s something more profound going on, though: “Thom chuckles, but it’s one of those chuckles where you laugh because it’s true, not because it’s funny…When you live inside of a future dystopia, you can’t really stop and comment on the omnipresent bleakness. When “bleak” is right there, it is no longer bleak. The fear is so near you can’t even see it. It is just…normal. Cue the APPLAUSE sign.”

Hyden makes somes good-natured wisecracks at his own writerly expense. For example, he “felt personally and professionally implicated” by the 2012 documentary Room 237, about people who watched The Shining enough times to start spinning elaborate conspiracy theories about its supposed deeper implications. I like this kind of obsessive criticism when it is based on something substantial. “Maybe/ I think you’re crazy” goes the chorus of arguably the most romantic song Radiohead ever wrote. Hyden is a passionate and erudite fan of the music, but he hasn’t reached an excessive level of nuts; he makes sure to ground his observations in reasonable speculation and specific information. As a nod to fellow music nerds, Hyden includes a mixtape of the Platonic ideal version of songs that appear on Kid A and Amnesiac, bootlegs included, which makes for a fine record in itself.

One of the paradoxes about Radiohead is that they tend to make lots of anti-anthemic sounding anthems, if such a thing is possible. “How To Disappear Completely” is gorgeous, a lighter than air acoustic lullaby that ponders the state of mind of some kind of eerily contented posthuman ghost: “I walk through walls/ float on the Liffey/ I’m not here/ This isn’t happening.” Their songs are often jittery, twitchy, nervous even in their cold splendor. “The National Anthem” (my favorite) mixes a surging, aggressive repeated riff as Yorke wails about how “everyone is so near” while sounding like he’s trapped inside of an empty swimming pool as a hell’s chorus of free jazz horns caterwauls behind him.

“Everything In Its Right Place” is, for Hyden, Kid A’s key song: “the conception, writing, and recording of this song is kind of the point of Kid A.” The hushed vocals and the warm but ominous keyboard riff underscore the implicit OCD the title suggests. Everything just ain’t in its right place, which is kind of how a lot of people feel these days, still. Hyden explains how the rather weird lyric “yesterday I woke up sucking on lemons” was a self-deprecating line of Yorke’s that reflected his rather sullen disposition at the time. Being anointed the voice of your generation will do that to you, it seems.

Especially when that generation, too old to be Xers and too young to be Millennials, came of age with the birth of the internet, Y2K, Bush V. Gore, 911, the second Iraq War. Economic precarity, the gradual omnipresence of screens, the constant montage of glittering images designed to allure and distract, pixels buzzing and whirring everywhere. Maybe Radiohead captured the sound of cyberspace itself — distant, allusive, dense, and vaguely ominous.

Especially when that generation, too old to be Xers and too young to be Millennials, came of age with the birth of the internet, Y2K, Bush V. Gore, 911, the second Iraq War. Economic precarity, the gradual omnipresence of screens, the constant montage of glittering images designed to allure and distract, pixels buzzing and whirring everywhere. Maybe Radiohead captured the sound of cyberspace itself — distant, allusive, dense, and vaguely ominous.

They certainly weren’t one of the godlike bands of previous decades. “When you heard Radiohead,” observes Hyden, “you were reminded that no matter how cool you looked in shades and a leather jacket, or how entertained you were by watching VH1 for five hours straight, it would not make the world any less frightening. The whole point of their records was that there were no answers, because the beasts at the door were vicious and defiantly post-logic.”

Radiohead as a band has always been reticent about making the kind of Big Public Statements emitted by rock stars of previous generations. The messages, if you wanted to take them as such, tended to be like flashing warning signs; ice age coming, ice age coming, paranoid android, I’m a reasonable man get off my case, hail to the thief, no alarms and no surprises please. You know you’re in a special historical moment when a band that you and millions of other people have loved for years writes a beautiful song that calmly states: “don’t get any big ideas/ they’re not going to happen.” I wonder what John Lennon, had he survived to a ripe old age, would have said about that.

I agree with Hyden that, probably due to my age more than anything else, OK Computer will always be my Radiohead record. Or maybe it should really be The Bends. I’ve never forgotten hand-writing my English papers in freshman year of high school while listening to “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” (A lot of what your aesthetic education depends upon what you were listening to when you were fourteen.) Radiohead became a soundtrack for the malaise that begins to sets in whenever one finds out that the best they can be isn’t good enough.

In addition, Hyden notes that Radiohead has become one of the few bands whose fanbase legitimately spans decades. An even more distinctive accomplishment, their songs continue be events, still very much part of the zeitgeist as it zigzags over the decades. Maybe Radiohead has become a Greek chorus for how little things have changed with the arrival of the new century, wailing beautifully out in the ether, to borrow a phrase from Robert Lowell, like “a ghost/ orbiting forever lost/ in our monotonous sublime.”

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.

Nice article but the phrase is “as is his wont”

Not want.

Wait,

Especially when that generation, too old to be Xers and too young to be Millennials,

This is backwards. Gen X was older than Millennials.