Classical Album Review: Commedia dell’arte Clowns in a World of Heartbreak

Dohnányi and Schnitzler’s “pantomime” The Veil of Pierrette receives its first, and resplendent, recording.

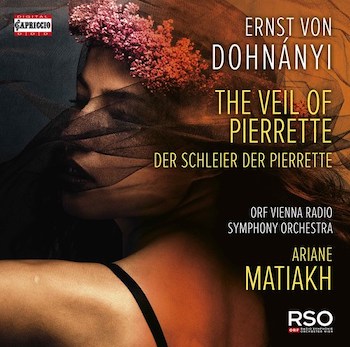

Ernst von Dohnányi: The Veil of Pierrette (“pantomime”).

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony, cond. Ariane Matiakh.

Capriccio 5388 [1 CD] 81 minutes

Click here to purchase and to hear a sample track

White-faced clowns whose hearts can break, puppets who come to life—not-quite-human characters such as these have recurred in theatrical life across the centuries: from baggy-pants street-theater performers in Renaissance Italy to modest Punch-and-Judy hand-puppet shows in England to the eighteenth-century comedies of Carlo Gozzi to Leoncavallo’s opera Pagliacci, Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka, and beyond. In the 1999 film Being John Malkovich, youngish, amoral experimenters manipulate the mind and body of the title character, turning him into a full-sized, warm-blooded marionette. Stage directors and costume designers have delighted in the defamiliarizing that comes with painting a character’s face into an expressionless or exaggerated mask (Tamino and the Queen of the Night in Julie Taymor’s The Magic Flute at the Met).

Perhaps the heyday of this fascination with de-individualized characters was the early twentieth century, when many theater folk were eager to reject Romanticism. The movement took many forms: from the abstract yet richly three-dimensional stage sets proposed by Adolphe Appia for Wagner’s operas in the 1890s and the modernist experiments with stage lighting by Edward Gordon Craig (in books from 1911 and 1913) to William Butler Years’s ritualistic At the Hawk’s Well (1916), which combined a tale from Irish mythology with spare costumes, masks, and sets—elements heavily inspired by Japanese Noh drama. Related trends outside the theater included the semi-abstraction of the human face in Picasso’s cubist paintings, inspired in part by highly stylized African tribal masks, as in the famous Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).

Smack in the middle of all this came Austrian-Jewish dramatist and novelist Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), best known today for his play Reigen (1897; often called La ronde), and the 1926 prose work Traumnovelle, i.e., Dream Novel. (Decades later, Stanley Kubrick would take Traumnovelle as a starting point for his attention-getting—I’d say overpraised—1999 film Eyes Wide Shut. Editor’s Note: Interestingly, Nicole Kidman, who stars in the Kubrick film, was also at the center of the 1998 staging of David Hare’s Blue Room, an adaptation of Le ronde.)

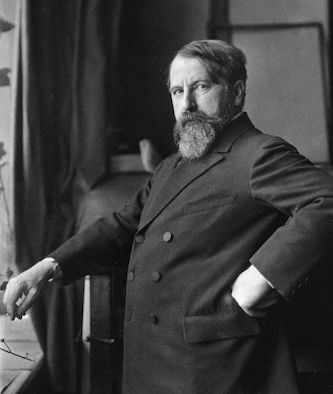

Arthur Schnitzler in 1912, two years after the premiere of “The Veil of Pierrette.”

In 1909-10, Schnitzler collaborated with an extremely talented composer, Ernst von Dohnányi (1877-1960), on an 80-minute-long dance work involving Pierrot, Pierrette, and Harlequin, three of the standard figures from traditional Italian commedia dell’arte and its various international offshoots. Though the work is labeled a pantomime, it was apparently a kind of ballet. It has now received its world-premiere recording, a first-rate one, undermined only by an inadequate booklet-essay.

Der Schleier der Pierrette (The Veil of Pierrette) was first performed in Vienna, 1910, and is in three acts, short enough that they might better be called scenes. It tells a tragic tale of a woman torn between two men. Similar love triangles occur in other highly effective shortish operatic works from the decades just before and after 1900. Notable examples include Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, Puccini’s Il tabarro, and two German-language versions of Oscar Wilde’s A Florentine Tragedy: one by Alexander von Zemlinsky, the other by Richard Flury.

Schnitzler’s scenario—summarized too briefly in the booklet essay—has a somewhat wobbly tone, at once sentimental and arch. Unlike in Pagliacci, the three main characters are not actors with real human names (e.g., Nedda and Canio) who, at one point, put on costumes and garish face-paint to play the roles of Harlequin (Arlecchino) et al. for an onstage audience. Rather, they are those stage characters (here called Pierrot, Pierrette, and Arlecchino), all the way through. Stravinsky’s Petrushka offers a close parallel, because it, too, is a danced work (not an opera) and because its characters are likewise not humans but theatrical stereotypes from beginning to end, yet living out real joys and woes.

In Der Schleier, Pierrette and Pierrot love each other, but, flighty thing that she is, she has agreed to marry Arlecchino. The two P’s, in despair, decide to drink poison together in his room. Pierrot imbibes and dies, but Pierrette cannot carry through with her part of the deal. At the wedding festivities for Pierrette and Arlecchino (in her parents’ ballroom), the ghost of Pierrot returns, sheathed in a veil that Pierrette had left behind. Arlecchino and Pierrette hasten to Pierrot’s room and find him dead on the floor. Arlecchino props the dead body up and reenacts the lovers’ farewell supper. (This is surely the most attention-getting and ghoulish bit in Schnitzler’s whole scenario.) Arlecchino leaves, locking Pierrette in the room with Pierrot’s corpse. She dances around it, then drops dead. (Did this work, I wonder, influence the ending of The Rite of Spring, three years later?)

Because nobody sings in Der Schleier, you can sit back and enjoy the music’s intriguing contrasts of mood and style: a waltz, a quadrille, some romantic yearning, a march-like passage, some intense grimness, and so on. (Several tracks can be heard for free on YouTube.) The synopsis in the booklet gives a general sense of what is happening. Alas, it lacks track numbers and is far too brief, not so much as mentioning the many other characters who, the cast list in the booklet tells us, populate certain of the scenes: Pierrette’s parents, a fat pianist, a gigolo, Pierrot’s friends Fred and Florestan, and so on.

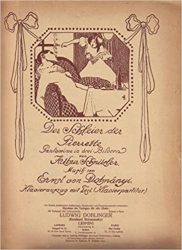

Composer Ernst von Dohnányi in 1905.

If you are in a studious mood, you can download the full score from IMLSP (for free!) and imagine a specific choreography on the basis of the extensive stage directions strewn throughout—which presumably amount to more or less the scenario that Schnitzler provided to the composer. Why weren’t all these crucial descriptions reproduced in the booklet? Or at least made available online in a convenient running text, with added track numbers? Still, even from the limited information provided, I figured out that, for example, a passage after the Wedding Waltz likely coincides with the entrance of the ghostly Pierrot (jagged phrases in low strings, then intense chords in the brass).

The music is tuneful, varied, and holds the attention. Dohnányi was a highly traditional Hungarian-born composer and pianist who ended up (thanks to Hitler) teaching at Florida State University. He is best known today for just a handful of works, including the long-beloved Variations on a Nursery Tune (which I, unlike many others, find rather inert), Ruralia hungarica for orchestra, a marvelous early Piano Quintet Op. 1 (admired by Brahms), and the enchanting Serenade for String Trio, Op. 10.

The Veil of Pierrette shows Dohnányi as skillful and (given the startling goings-on) rather straightforward, with little Schnitzlerian irony or bizarreness. The music sounds like a blending of Lehár (of The Merry Widow fame) and the more accessible Richard Strauss (such as the latter’s incidental music to Moliére’s Le bourgeois gentilhomme), with, to my ear, a brief pre-echo—at one point—of Puccini’s Turandot. One recurring theme engenders several others of contrasting character (much as in Wagner’s Ring Cycle). Throughout, the orchestration is exquisitely worked out, but the harmony relatively conventional, without the bite and variety of other works from 1910, e.g., by Debussy or Mahler. Perhaps the strongest extended section, the aforementioned Wedding Waltz, became a staple for silent-film accompaniment.

I would love to see the thing danced, with the shifting dramatic tones given full embodiment. Maybe the choreography would provide the ironic distancing, creepiness, and emotional complexity that I sometimes find lacking in the music. Dance works often create profound effects through rich body language, gripping character interaction, and powerful staging—all laid over relatively straightforward music. (Think of the effect that certain supernatural and ghostly characters make in such ballets as Adolphe Adam’s Giselle or Tchakovsky’s Swan Lake.)

The work would form an intriguing double-bill with Petrushka, or with some other dance-work using heavily symbolic characters: say, Milhaud’s La création du monde or Bernstein’s The Dybbuk. Even without any visual component, it makes for a pleasant and diverting hour-plus. The Vienna Radio Symphony plays marvelously (not least in that splendid waltz), and French-born conductor Ariane Matiakh takes an active role, shaping phrases and adjusting tempos in a way that helps hold the attention. (YouTube has an interview with her about Dohnányi’s score. The recording is available as a CD and also through various streaming services.)

The work would form an intriguing double-bill with Petrushka, or with some other dance-work using heavily symbolic characters: say, Milhaud’s La création du monde or Bernstein’s The Dybbuk. Even without any visual component, it makes for a pleasant and diverting hour-plus. The Vienna Radio Symphony plays marvelously (not least in that splendid waltz), and French-born conductor Ariane Matiakh takes an active role, shaping phrases and adjusting tempos in a way that helps hold the attention. (YouTube has an interview with her about Dohnányi’s score. The recording is available as a CD and also through various streaming services.)

Fans of the composer, of ballet music, and of theatrical experiment through the ages will be intrigued to hear Dohnányi’s Veil and to imagine the work as it might be carried out on stage. It was much performed at the time, including in Prague, Budapest, Moscow (directed by theater reformer Vsevolod Meyerhold), and eventually New York City (by followers of Konstantin Stanislavski, 1928).

It might fascinate and even move audiences again today.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book. His reviews appear in various online magazines, including The Arts Fuse, NewYorkArts, Naxos Musicology International (for subscribers to Naxos Music Library), and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Tagged: Arthur Schnitzler, Capriccio, Ernst von Dohnányi, Ralph P. Locke