Literary Appreciation: D. H. Lawrence’s “Women in Love” at 100

By Roberta Silman

I hope this centennial will inspire readers to immerse themselves in this enormously important, rich, and vibrant work.

Women in Love, D.H. Lawrence, 1920

Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount, is a cultural anchor here in the Berkshires, and its gardens are wonderful, like a quick trip to France, I have often told my children and grandchildren. It was particularly gratifying that its wonderful director Susan Wissler opened the grounds as soon as the pandemic started and is now hosting some events on the porch café, as well. All this by way of saying that’s how I realized it was a hundred years since Wharton’s Age of Innocence was published. Although she had already had a best seller — The House of Mirth in 1905 — and had published what I consider her masterpiece, Ethan Frome, in 1911, Wharton’s place in the canon was assured when she won the Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Innocence, the first woman to do so. So I reread the novel and, although I admired it and also admired the newest film iteration with Daniel Day Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer, this was not a book really close to my heart.

Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount, is a cultural anchor here in the Berkshires, and its gardens are wonderful, like a quick trip to France, I have often told my children and grandchildren. It was particularly gratifying that its wonderful director Susan Wissler opened the grounds as soon as the pandemic started and is now hosting some events on the porch café, as well. All this by way of saying that’s how I realized it was a hundred years since Wharton’s Age of Innocence was published. Although she had already had a best seller — The House of Mirth in 1905 — and had published what I consider her masterpiece, Ethan Frome, in 1911, Wharton’s place in the canon was assured when she won the Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Innocence, the first woman to do so. So I reread the novel and, although I admired it and also admired the newest film iteration with Daniel Day Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer, this was not a book really close to my heart.

But what else had been published in 1920? Thanks to Google I found an impressive list: Cherí by Colette, Main Street by Sinclair Lewis, Miss Brill and Other Stories by Katherine Mansfield, This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Women in Love by D.H. Lawrence, The Guermantes Way by Marcel Proust, as well as work by Agatha Christie, Queen Lucia by E.F. Benson, Rescue by Joseph Conrad, and The Story of Dr. Doolittle by Hugh Lofting.

I have always loved Lawrence’s short stories and read several of them carefully when I was working with Grace Paley at Sarah Lawrence in the early ’70s for my MFA. I had also loved Sons and Lovers and The Rainbow, but I had never read all of Women in Love. During this bizarre period of isolation, it seemed the right time to reread it to the end.

It is an amazing book. Its themes are as relevant today as they were a hundred years ago — friendship, sisterhood, sexual love both between men and women and men and men, the place of power and freedom in such relationships, the need for privacy, the importance of physical touch in our lives, how intimacy can uplift and disappoint, the disparity between those brought up to money and those in poverty, the beauty and ugliness of a landscape that has succumbed to the Industrial Revolution, critical notions of class in English society and on the Continent, man’s place in the natural world, the meaning of mortality and immortality, and, finally, the ultimate question of what makes life worth living. As you read there are times when you feel that Lawrence wrote this novel with his blood, from the very depths of his soul. And, although his reputation was somewhat tarnished not long before he died with the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, it is easy to see why E.M. Forster wrote after the writer’s death in 1930 that Lawrence was “the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation.”

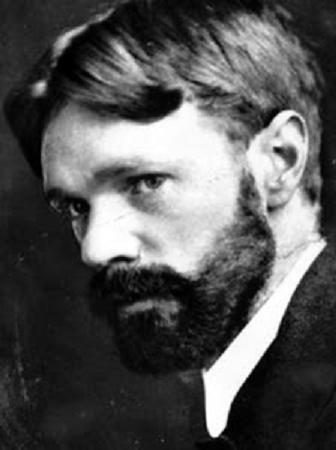

Born in a Nottinghamshire (Robin Hood country) mining family in 1885, David Herbert Lawrence seemed to live at a higher than normal pitch from the time he was a boy. He not only noticed things, like Thomas Hardy and Henry James; he also felt things more acutely. Unusually sensitive to the strife between his parents, he spent a great deal of time as a teenager with Jessie Chambers (the model for Miriam in Sons and Lovers) and her family. And perhaps most crucially, like many talented people, he didn’t fit in. Moreover, his need to question so many of the tenets of his provincial upbringing revealed an enormous ambition that no one seemed to know how to cope with.

A much-talked-about scene from Ken Russell’s 1969 film version of Women in Love, a naked wrestling match between Rupert Birkin (Alan Bates) and Gerald Crich (Oliver Reed).

His love of books led him as far from the mines as possible, first as a pupil-teacher at Eastwood, and then as a full-time student at University College, Nottingham (an external branch of the University of London), from which he earned his teaching certificate. But he was already writing, and after Jessie sent some of his poetry to the editor of The English Review, Ford Madox Ford, who was at that time known by his given name, Ford Hueffer. He recognized Lawrence’s talent and the writer soon found his way to London and the literati there. In 1912 he met Frieda Weekley, a married woman with three children who was six years older than he. It seemed impossible, but she left her family and she and Lawrence “eloped” and eventually married in 1914, staying together until his early death in 1930 at the age of 44. Frieda was German-born and had become an object of scorn during the run-up to the First World War; they were suspected of being spies and left England forever in 1918. The couple wandered, thus giving Lawrence material for the outstanding travel books he wrote in addition to his superb stories and novels.

Women in Love is actually a sequel to the three-generational novel The Rainbow about the Brangwen family. This time, though, it focuses on the two sisters, Ursula, now 26, and Gudrun, 25, a teacher and an artist who are trying to figure out their futures. It is widely believed that Ursula and her lover and husband Rupert Birkin are based on Lawrence and Frieda, and Gudrun and Gerald Crich are based on their friends Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry. Much ink has been spilled on that assumption, but these four characters are so compelling and complicated that bringing in the baggage of real lives seems irrelevant. However, one character, Hermione Roddice, is clearly based on Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) the English society hostess who seemed to know everyone in the arts in the early part of the 20th century in England. She was a very tall, outrageous woman whose colorful clothes set her apart and who figures in every book about the Bloomsbury group, usually portrayed as the earth mother figure to younger men (whom she sometimes bedded) and a figure of both mockery and fear to the women. A recent biography of Morrell by Miranda Seymour told a quite different story, of a woman with unique talents and skills, but what comes through in Lawrence’s novel is her magnetism and power, which threatened Frieda in real life and certainly poses problems for Ursula.

D.H. Lawrence, Photo: Walter Benington.

The narrative thrust of the novel is about marriage — will these two women marry these two men? But this is hardly a plot driven book; rather, it is more about people thinking through their actions, even when faced with crises. The prose is not nearly as tight as in the stories and there have been critics who complained about the hesitations, the repetitions, the circling back to the same questions. This is clearly a book that could be edited and probably would be, heavily so, if it were published now. Yet part of its power lies in those repetitions, which pull us so quickly into the lives of these rounded characters — to use Forster’s metric — whose minds go off in so many directions, just like our minds do.

Rupert is slight, more intellectual, sensitive, thoughtful, and attuned to women, even in his observations of their clothes and makeup and hair. He is also more sophisticated in his view of the world. Crich is stocky, the son of an industrialist, rougher around the edges and more inclined to action than thought. He is also more of a playboy (there are some marvelous scenes about Gerald’s set in London that resemble early Fitzgerald and Hemingway) and more troubled because, as we learn early, he accidentally shot his brother when they were boys. These very different men develop a deep bond that has been debated by readers and critics these last hundred years. Are they bisexual, and what really transpires between them? Reading this novel now, in a more tolerant age, you realize that Lawrence is exploring the temptations of male friendship in all its facets. In fact, that is part of the book’s staying power, which is why it is so pertinent when we are finally facing so many questions about sexuality and gender.

In comparing the sisters, Ursula is more practical and more pliable, while Gudrun is more romantic, more imaginative and artistic, fiercely determined to be on her own. Their sisterhood is mostly calm and close and serves as ballast for the more volatile friendship of Rupert and Gerald. In the end, though, this book really belongs more to Gerald and Gudrun and their endless struggles with each other and what they perceive as their places in the world. We see the Crich family in action, especially in the vivid chapter called “Water-Party,” which ends in tragedy. We also get to know the more middle-class Brangwens; there is not only Laura Crich’s wedding at the story’s beginning, but also the portentous drowning referred to above, as well as natural deaths and wanderings through the Midlands and travels to the continent. And continual wondering and wrangling about all the important mysteries.

Here is Rupert mulling about halfway through:

In the old age, before sex was, we were mixed, each one a mixture. The process of singling into individuality resulted in the great polarisation of sex. The womanly drew to one side, the manly to the other. But the separation was imperfect even then. And so our world-cycle passes. There is now to come the new day, when we are beings each of us, fulfilled in difference. The man is pure man, the woman pure woman, they are perfectly polarised. But there is no longer any of the horrible merging, mingling self-abnegation of love. There is only the pure duality of polarisation, each one free from any contamination of the other. In each the the individual is primal, sex is subordinate, but perfectly polarised. Each has a single, separate being, with its own laws. The man has his pure freedom, the woman hers. Each acknowledges the perfection of the polarised sex-circuit. Each admits the different nature in the other.

When the foursome decide to go to the continent, the writing becomes surer and truly beautiful — the descriptions of the snow and skiing in Austria are as good as anything you will ever read. Moreover, the depiction of the artist Loerke (possibly based on the artist Mark Gertler) is accomplished with such finesse and the discussions about art and life so natural that the surprise ending somehow seems as inevitable as a Greek tragedy. By then we have come from what seemed at first to be another Victorian novel of manners to something far more daring and wild. Even surreal.

Roughly 50 years before Women in Love Tolstoy had written his masterpieces, War and Peace (1867) and Anna Karenina (1877), which changed the course of world literature and are still probably my favorite novels. And, smack in the middle of that time, George Eliot’s Middlemarch was published in 1871, another of my most beloved novels. And two generations later here is Lawrence, coming from out of the blue and braiding these two visions of what fiction could be, breaking new ground, as Forster recognized. Although Lawrence is not read as widely now as when I was in college in the ’50s, I hope that this centennial will inspire readers to immerse themselves in this enormously important, rich, and vibrant work, which shocked so many of his countrymen when his books were published in rapid succession — remember his early death — but which seems uniquely suited to these challenging and often troubled times.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

So good to have this celebration of Women in Love. One of Lawrence’s merits, particularly with the worsening of the Climate Crisis, is his lyrical defense of nature against the savage exploitation of the budding industrial/technological complex. He explored how its damage was spiritual as well as material. There is a robustly combative toast to Lawrence in Paul Kingsnorth’s Savage Gods:

He was one of the first to ask what has now become an elemental question: Are we creating a world, a society, a culture, worth living in?

Since we are on Lawrence, I would highly recommend looking at his essays and reviews as well — he was a marvelous travel writer, a fascinating if eccentric critic. His polemics — on politics and psychology, male and female — are hysterical and hold up badly today. A new anthology edited by Geoff Dyer The Bad Side of Books focuses on his writing on books and art, though some of his brilliant travel writing is there. I would also get a hold of the old Penguin edition Selected Essays, edited by Richard Aldington. The latter contains Lawrence’s zesty take down of John Galsworthy, a wonderful exercise in cutting criticism: “When one reads Mr Galsworthy’s books it seems as if there were not on earth one single human individual. There are all these social beings, positive and negative.” A quick hit of Lawrence’s genius — read “Whistling of Birds.” It is in both collections.

A beautiful appreciation, so well written and so knowledgeable. I loved reading this piece. I have the tiniest question. When you say Lawrence’s reputation was “tarnished” by Lady Chatterly, do you mean it’s a bad book or a notorious book? I haven’t read it in many years but remember really liking it.

Hi, Gerry,

I used “tarnished” to reflect how the book was received. People were shocked, not only by the sex depicted but — and I think this was even more the case — by the fact that an aristocratic woman had had anything to do with an uneducated game-keeper who was so rough around the edges. I think Lawrence hit a nerve and everyone went crazy. But this was one of the themes of a lot of his work. And, remember, Clifford Chatterley was impotent because he was paralyzed from the waist down. What interested Lawrence, I think, was that a marriage needs the physical bonds as well as the mental. That’s why Lady Chatterley was so lonely, and needy. A lot of people think she has many of his wife Frieda’s characteristics. Not surprising. So does Ursula in Women in Love. But I think that is a slippery slope.

I haven’t read the book since college but I do remember that people there thought it was more carelessly written than his earlier work, perhaps because he was so sick with TB. He probably knew he had only so much time left. He died a year after it was published.

I’d like to add my praise for this piece, I really enjoyed reading it too. I had a real engagement with The Rainbow, when I read it however long ago, and it hit me in the gut how accurate his description of dysfunctional male and female relationships really were. Maybe it was learned at home.

His studies in American literature is one of those books I’ve read a lot about but not the primary text itself. And the insights from it are very useful.

Maybe we are just now catching up w his vision, at least in some ways?

This analysis is kind of fluttery, I have personally interacted with the book more often. Talk of the tales of modernism, D.H. Lawrence is a fighter who believes in modernism and realism….we can write write and write, that is basically what the writer stated anyway.