Jazz Album Review: Ken Field’s “Iridescence” — Some Enchanted Strangers

By Michael Ullman

Iridescence is a masterful set, with none of the tentative feeling … he bipped when he should have bopped … that sometimes afflicts free jazz outings.

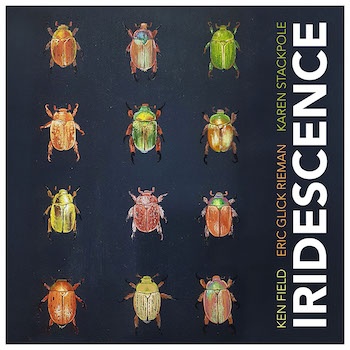

Iridescence, Ken Field (Ravello Records)

The leader of the Revolutionary Snake Ensemble, saxophonist Ken Field, explains in his notes the serendipitous genesis of his new trio record, featuring percussionist Karen Stackpole and Eric Glick Rieman on prepared piano. Essentially, he is an opportunist. The way Field tells it, Iridescence was the result of a happy accident.

Field started recording back in the ’90s. He is well known to Bostonians, both for his own groups and for his appearances with Birdsongs of the Mesozoic and various bands led by Darrell Katz. He was recently coming back to Massachusetts from Australia, where he has an “annual gig.” He had a two-day layover in San Francisco, and he wanted to fill in the time with a performance. He found a space, and then the keyboard player, Rieman. He decided to look for a percussionist to take part in this last-minute event. The last piece of the triangular puzzle turned out to be the “fantastically creative percussionist and gong player Karen Stackpole.” He continues: “The three of us had never met or played together, so it was an evening of totally spontaneous improvisation.” Field played the two instruments he had with him: sopranino saxophone and flute.

No one would have guessed that these were three strangers making music. Iridescence is a masterful set, with none of the tentative feeling…he bipped when he should have bopped…that sometimes afflicts free jazz outings. Nor is there any self-indulgent shouting. The opening number, the (perhaps) ironically titled “Inside,” begins with eerie, faintly metallic sounds in the background. It is difficult to identify the provenance of some of what we hear here — it could be the faint ringing of a cymbal or gong. Almost immediately, Field enters, confidently, on flute and supplies a succession of bold, increasingly excited phrases that are closely recorded and follow what seems to be a natural ebb and flow. Once he recedes, tones (some monotones) emerge in the background. After about two and a half minutes, Field introduces a new melody; he dominates this first piece.

“Ice” is more of a group effort. After Field has played a single, sagging note, Rieman offers a series of nervous counter statements on piano, with Stackpole striking out intermittently, generating clanging metallic sounds on cymbals. Toward the end of “Ice,” Field plays low moaning sounds; Stackpole follows up with a succession of metallic clinks and clanks under Rieman’s gradually subsiding piano. The conversation here strikes this listener as humorous. Each piece generated its own distinctive aura. “Cinders” begins threateningly, with an anxious rustling from the percussionist, who continues with single strikes on a gong alternating with a succession of relaxed sonic bits on cymbals, wood blocks, and shakers. At first, she is joined by a single held note on piano. Later, in the background, we hear a faint held note, but Stackpole is pretty much alone here until the piece is a quarter over. Then Rieman enters on piano. After the preceding shudders and shakes, Rieman’s piano sounds almost startlingly solid. He slowly focuses on a single four-note phrase, repeating and then expanding it. Stackpole comes in with a kind of jolty commentary and “Cinders” almost swings.

The jaunty “Rise” begins with a junkyard clamor that subsides immediately. Then Rieman plays a tentative series of single notes underneath the long tones of Field’s saxophone. It’s an oddly contradictory opening, a bang followed by a series of whispers. Rieman performs on a piano that is sometimes muffled in an odd way. The two begin a dialogue. Field changes the mood about three and a half minutes into “Rise” via an almost vulgarly outgoing phrase. It’s as if he just discovered his Dixieland roots. After about another minute we begin to hear, in the background, sounds from the percussionist. But there’s more to come. Rieman plays a series of phrases that could have come from a music box and then a peculiar stride piano. Field offers some bent notes: Sidney Bechet couldn’t have done it better. It’s as if a different, older form of music wants to crash the free jazz party. The last piece,”Recede,” kicks off with Stackpole’s bevy of half-swallowed sounds. Inevitably (given the title) it is the most low key of the five pieces on the album. Under a lot of the track there’s the sound of a strummed string instrument; I assume it’s Stackpole. Field switches to flute for the ending, supplying some sensitive solo phrases. This is a group that respects the individual voice, even as it makes compelling music together.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Eric Glick Rieman, Iridescence, Karen Stackpole, Ken Field