Book Review: “Great Demon Kings” — A Comet Circling Gas Giants

By Peter Walsh

John Giorno was in the vanguard of what later became the herd: Ginsberg, Kerouac, Warhol, Buddhism, Burroughs, enlightenment, spiritual quests to India, unfettered sex, wild poetry, new technology, experimental forms of expression, queer politics, pot, speed, LSD — all the household bric-a-brac of the counterculture.

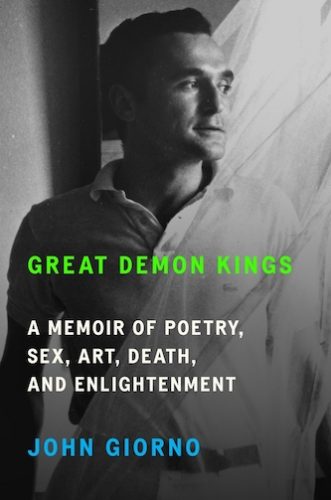

Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment by John Giorno. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 368 pages, $28.

The poet and performance artist John Giorno died in 2019 after an eventful life and a long career. He published more than a dozen books, with titles like Balling Buddha, Cunt, CUM, Cancer in My Left Ball, Shit, Piss, Blood, Pus & Brains, and Suicide Sutra. He lived in Manhattan during the culturally fertile and turbulent ’60s, and ’70s, when he partied with, as he puts it, “everyone in the art world, before they were famous.” Tiny Tim performed at his 27th birthday party. He had a project featured at the Museum of Modern Art and he performed at the Pompidou Center in Paris. In later life, he was an AIDS activist and devotee of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Yet he will probably always be best remembered for something he did in his sleep as the star and sole subject matter of Andy Warhol’s early, five hour and twenty minute film, Sleep (1964).

The circumstances of this film, his love affair with Warhol, and much, much more, are recounted in Giorno’s new memoir, Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment. The list of Giorno’s superstar lovers alone — besides Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, William S. Burroughs, and other lesser-known but important men in the art world— should be enough to attract the attention of anyone with a passing interest in Manhattan’s late-century downtown art scene. Will they find what they are looking for?

Memoirs are known to be eccentric and unreliable: a semifictional literary form. Less formal and complete than an autobiography, inevitably subjective, based on patchy memories and ego rather than the meticulous research of a scholarly biography, memoirs are a first draft of a life story — given to exaggerations, slipped dates, factual errors, apocryphal anecdotes, self-justifying screeds, heroic attempts to “set the record straight,” and acts of revenge. It must be said at the start that this one is stranger than most. (For me, reading it has been made even odder by the fact that I have seen, met, studied under, had dinner, or worked professionally with a number of the people mentioned in the text. Little did I know at the time.)

A note in the accompanying publicity materials describes the book as “the product of decades” and adds that the author “passed away [from a heart attack] a week after sending in his manuscript to his editor.” At one point in his narrative, Giorno describes himself as working on the book in 1992 with “Kirsten, a student intern.” Giorno is stuck with writer’s block on the title page of a chapter on Robert Rauschenberg, Giorno’s lover in the late 1960s. Kirsten, Giorno says, promptly leaks this information to Rauschenberg himself, while he is a guest at a black tie dinner. Rauschenberg, furious, threatens to sue, and John Cage, seated at Rauschenberg’s table, throws back his head in his signature laugh. Another member of the party jokes “He’ll wait until you’re dead.” “I will come back and haunt him.” Rauschenberg retorts

Despite its long gestation, the text hints that Giorno intended it for publication and during his lifetime. “I will be the one to write your story,” he thinks, after the collapse of a love affair in Tangiers. “You underestimate me. I will write about you, and the horror of it all.”

Born in 1936, Giorno grew up in comfortable circumstances in Manhattan and in an affluent Long Island suburb. He attended Columbia in the late ’50s. He recounts a visit of a friend, during Easter break of his sophomore year. “We were nineteen years old, poets. We drank a lot.” Around the same time, though he does not explain how, Giorno becomes prodigiously and exclusively homosexual. These twin identities became two of the tentpoles of the rest of his life.

Giorno is admitted to the pioneering Iowa Writer Workshop, then under the hand of its second and most prominent director, Paul Engle. After college, he heads off to Iowa City. But, for reasons that are not entirely clear, he doesn’t fit in. He soon falls into a deep depression and attempts suicide, losing most of his blood into his rented room mattress. Engle sends him home to Long Island, where he recuperates before taking a low-impact job with an old-line Wall Street firm.

In college and just after, Giorno was apparently one of those attractive young people who are invited to parties to form a kind of decorative backdrop for the more consequential guests. At this early stage, he often attends parties and visits artists’ haunts accompanied by a “girlfriend,” at a time when that word did not necessarily imply a sexual relationship. Not content to remain part of the wallpaper, he arranged to have himself introduced to an ever widening network of acquaintances, friends, and lovers among New York’s ’60s avant-garde. The scope is truly astonishing, including scores of prominent artists, dancers, writers, curators, and other figures from New York’s cultural elite. His life becomes a whirlwind of glamorous exhibition openings, wild loft parties, and love affairs with the great and famous.

Great Demon Kings unfolds mostly chronologically in no particular prose style. Giorno divides the book into four parts plus a prologue and epilogue. Parts 1-3 make up two-thirds of the book, but cover exactly seven years of the author’s life, from his mid-20s to early 30s. Part 1 opens in October 1962 with Giorno’s first meeting with Andy Warhol. Part 3 ends in October 1969 with the quiet conclusion of his love affair with Jasper Johns. This is the heart of the book, the dramatic core that will most interest scholars and probably the general reader. It could easily stand on its own.

Part 4 is much shorter and covers the remaining 30 years of the 20th century. These pages might best be described as “reminiscences.” The are filled with anecdotes and scattered accounts, probably written separately, of discrete events: a trip to India, a nasty cancer surgery, an orgy with Keith Haring in a subway men’s room, the AIDS crisis, the death of William Burroughs.

The final 20 years of Giorno’s life is covered in a scant, seven-page “Epilogue,” even though he describes these years as the time he did his best work and became known as a visual artist as well as a writer and performer. They correspond to his 20-year relationship with the Swiss-born artist Ugo Rondinone, nearly 30 years his junior, whom he marries in 2017. They seem to have been the happiest years of his life.

Unfortunately for historians of the period, there is a lingering, frustrating vagueness. Most of the illustrious figures he mentions remain little more than names on a guest list. The conversations he recalls are often either awkward, brief, party chatter or else so generally described that it is hard to know what they actually contained. He refers to “art world gossip” without going into any details. His comments on the ground-breaking art he sees limit themselves to threadbare superlatives: “magnificent,” “wonderful,” “truly great.” He describes his parents, who apparently cover his expenses well into adulthood, as generous and supportive to a fault. Otherwise he barely mentions them. He says nothing about his preteen childhood in ’40s New York or the rest of his Italian-American family. New York City itself seems reduced to the lofts, galleries, bars, studios, performance spaces, museums, and hangouts frequented by his celebrated friends.

Giorno’s love affairs with famous male artists and writers form the most sensational passages of his memoir. Even as a teenager, he circles cultural celebrities like a comet heading for a gas giant. Once an encounter has been made, things quickly become dramatic. Giorno shows a penchant for complicated love triangles and some of his scenes read like a Restoration bedroom farce as staged by the Marx Brothers. Giorno, though, maintains a Margaret Dumont-like deadpan throughout.

In the graphically described sex moments, probably the passages that will draw the most attention, the narrative finally snaps into focus. His descriptions are crude and impersonal, though, and Giorno provides more details than many readers will actually want to know: the size and shape of William Burroughs’s penis, Andy Warhol’s foot fetish, Rauschenberg’s love of anal sex, the play-by-play of a reluctant threesome with Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg.

These relationships usually start off hot but cool off in a few months, for somewhat, at least to Giorno, mysterious reasons. Warhol and Rauschenberg, in particular, seem extraordinarily kind and supportive — including Giorno in their work, introducing him to their friends as a “young poet,” taking him to endless parties, openings, and performances, and helping him hook up with important collaborators like Robert Moog, inventor of the Moog synthesizer.

After much importuning on Giorno’s part, Warhol even gives him a major painting from his “Death Series.” Years later Giorno casually sells it for $30,000, of which he actually collects only half. Today, the work would bring, at auction, well into eight figures.

But Giorno is never entirely satisfied. He feels appreciated for his sexual skills, but underestimated as an artist. Maybe he is “just a piece of meat,” he worries, and will be dumped for someone more interesting. When Rauschenberg goes to Los Angeles on an extended work trip, he meets movie stars like Warren Beatty and Shirley MacLaine. Giorno assumes he will throw over his New York friends for more glamorous ones from Hollywood.

Insecure about his poetry (as in Iowa, he never connects with any of the more established literary cliques of his time), Giorno frets that people interested in publishing his work or in collaborating on performances are really just trying to get closer to his famous boyfriends. He complains about the “ego” of his partners and suspects their motivations.

After the success of Sleep, whose genesis and creation Giorno describes in detail, he pesters Warhol to feature him in another film. He says he wants to be a star, “like Marilyn Monroe.” Eventually, Warhol shoots some footage of Giorno for something called “Hand Job,” but he is not happy with it and abandons the project. Later Warhol makes Blow Job (1964) with someone else. Giorno is “deeply offended. That was supposed to be my movie, I thought…. It was going to be my starring role, and he gave it to somebody else. I was devastated and furious…. I couldn’t help but see it as a sign…. Andy was moving on, as I always suspected he would.”

After the success of Sleep, whose genesis and creation Giorno describes in detail, he pesters Warhol to feature him in another film. He says he wants to be a star, “like Marilyn Monroe.” Eventually, Warhol shoots some footage of Giorno for something called “Hand Job,” but he is not happy with it and abandons the project. Later Warhol makes Blow Job (1964) with someone else. Giorno is “deeply offended. That was supposed to be my movie, I thought…. It was going to be my starring role, and he gave it to somebody else. I was devastated and furious…. I couldn’t help but see it as a sign…. Andy was moving on, as I always suspected he would.”

Giorno keeps his hurt feelings to himself and does not record any confrontations, but the invitations start to slack off and, fearing the worst, he cuts Warhol off without explanation. He later does much the same thing with Rauschenberg, who had kept his live-in boyfriend, the dancer Steve Paxton (an earlier fling for Giorno), throughout their affair. Yet there is no objective sign that either artist wanted to end the relationship. Both remain at least outwardly cordial and friendly for years afterwards; both agree to design covers for Giorno’s first book of poetry (the Rauschenberg is used).

At the very end of Part 3, Giorno’s friend, the poet Anne Walkman, publishes a poem based partly on visiting him during his last vacation with Jasper Johns in Nags Head, NC. Waldman writes about Johns at length but does not mention Giorno. “[S]he had eliminated me from her story about Jasper…” Giorno writes. “It felt all too familiar; as I had with Andy and then Bob, I was being edited out of my lover’s stories.”

In fact, a quick review of standard biographical sources on Rauschenberg and Johns yielded no references to Giorno at all. Giorno was himself a source for Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol (Scherman and Dalton, 2009) where he is named first as “an aspiring poet” and later as “a stockbroker.” The book quotes Giorno on several events that took place during the early ’60s, when Giorno and Warhol were regular companions, though the sexual side of their relationship is described, by Giorno himself, as negligible. The authors recount the creation of Sleep in detail, but Giorno exits Warhol’s biography on a sour note. “He’s just a piece of meat,” the book quotes Warhol as saying in 1969. “Never thinks, has nothing to say. He saw my death pictures and decided to do death poems. I mean, I really know him — he’s a dunce.”

Although he does not mention her by name, Giorno seems to want to cast himself as a kind of American gay male Alma Mahler — a musician and composer whose successive marriages to three of the titans of Middle European modernism — Gustav Mahler, Walter Gropius, and Franz Werfel — has given her lasting fame. But Mahler took to her role as passionate, if not always faithful, companion and transcendent muse with great energy and intense devotion; she had a true influence on the culture of her times. Giorno, even on the pages of his memoir, seems inconstant and distracted. At a critical moment in his relationship with Jasper Johns, for example, he runs off to attend the Woodstock Music Festival with other friends. The reader, at least, is not particularly surprised when his affair with Johns ends soon after. Despite his efforts in Demon Kings to attach himself to the famous as a co-equal, Giorno often comes across as a celebrity-chasing jerk.

Giorno, a heavy drinker from his teen years, says he frequently mixed vodka and soda with a closet full of other drugs — cigarettes, pot, LSD, Dexedrine, cocaine. The drug use is an important part of his identity, working method, love life, and self-treatment for his recurring depressions. By his early 30s he seems more or less continually drunk or stoned. Thus it becomes impossible to sort out the truth of his account from the possible false memories, paranoid delusions, or unrealized fantasies. The general outlines of this story are well documented: Giorno kept a massive archive of his life, selections of which were exhibited shortly before his death, and he includes many photographs with his text. Yet the most sensational scenes here are intimate ones, and key witnesses, like Giorno himself, are permanently unavailable for comment. As a flawed first-person narrator, writing decades after the event, Giorno can’t be entirely trusted recalling the facts of his own life. We will never know how much of his book actually happened.

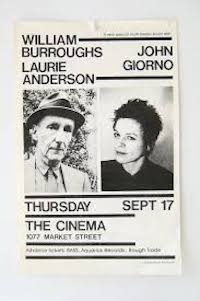

The memoir also never quite nails Giorno’s literary career, perhaps because it is so unorthodox. Giorno’s chosen profession stays in the background of his prose much of the time. His early verse included “found poems” — texts he discovered ready-made in subway posters, pornography, or newspaper stories and broke into poetry-like lines. His later performance-oriented work belongs to a period in the late ’60s and early ’70s in which there was an intense interest in cross-media collaborations, bringing together images, words, movement, music, light, sound, and technology in a single performance. “Dial-a-Poem,” Giorno’s most successful project, grew out of his attempts to use new technology to bring spoken poetry to new audiences and free it from the dusty pages of academia. It was this, Giorno’s performance-based work, that continued these experiments and influenced a later generation of poets and performance artists like Laurie Anderson, a sometime collaborator.

The memoir also never quite nails Giorno’s literary career, perhaps because it is so unorthodox. Giorno’s chosen profession stays in the background of his prose much of the time. His early verse included “found poems” — texts he discovered ready-made in subway posters, pornography, or newspaper stories and broke into poetry-like lines. His later performance-oriented work belongs to a period in the late ’60s and early ’70s in which there was an intense interest in cross-media collaborations, bringing together images, words, movement, music, light, sound, and technology in a single performance. “Dial-a-Poem,” Giorno’s most successful project, grew out of his attempts to use new technology to bring spoken poetry to new audiences and free it from the dusty pages of academia. It was this, Giorno’s performance-based work, that continued these experiments and influenced a later generation of poets and performance artists like Laurie Anderson, a sometime collaborator.

But a performance-based prosody might fade once its creator’s voice falls silent. A 1993 Library Journal review of a Giorno collection concludes: “his poems lie flat on the page, begging for a voice…” His lengthy New York Times obituary credits “his restless experiments in the circulation and political potential of poetry, which he felt had been unjustly overshadowed by other genres of expression.”

Giorno is said to be far better appreciated overseas than in the United States. But there is nothing much in Great Demon Kings to suggest Giorno was an under-recognized literary genius. His memoir lacks the narrative power and vivid descriptions of that other drug-soaked account, Thomas De Quincy’s classic Confessions of an English Opium-Eater; his writing style falls short of the perverse elegance the Sinologist and forger Sir Edmund Backhouse used in his equally sensational and graphic memoir of bisexual decadence in late Imperial China.

Nor does Giorno’s memoir have the charm, wit, and lifetime-wide perspective of Picasso biographer John Richardson’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, his memoir of his early life living with the art historian Douglas Cooper and his brilliant art collection in a ramshackle chateau in Provence, where Picasso was a frequent guest. Richardson, who has a brief walk-on part early in Giorno’s memoir, writes from a time in which Picasso and Cooper are both dead, the chateau sold, the collection dispersed, and his one-time famous friend Picasso has become the enduring focus of his life’s work.

Even as an incomplete historical document, though, Giorno’s book deserves to be published and possibly even read. He was in the vanguard of what later became the herd: Ginsberg, Kerouac, Warhol, Buddhism, Burroughs, enlightenment, spiritual quests to India, unfettered sex, wild poetry, new technology, experimental forms of expression, queer politics, pot, speed, LSD — all the household bric-a-brac of the counterculture. Many souls wandered through these years in American history, searching for enlightenment. Giorno was far more fortunate than most, and he lived to tell the tale.

May every drug I ever took

come back and get you high

may every glass of vodka and wine I ever drank

come back and make you feel really good,

numbing your nerve ends

allowing the natural clarity of your mind to flow free,

may all the suicides be songs of aspiration,

thanks that bad news is always true,

may all the chocolate I’ve ever eaten

come back rushing through your bloodstream

and make you feel happy,

thanks for allowing me to be a poet

a noble effort, doomed, but the only choice.

A stanza from John Giorno’s Thanx 4 Nothing (on my 70th birthday in 2006).

A link to Giorno reading the complete poem.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.