Film Review: Writer Flannery O’Connor — A Singular and Mysterious Consciousness

By Gerald Peary

With its many virtues, Flannery isn’t the perfect film biography. It’s a shoot-by-the-numbers conventional PBS American Experience.

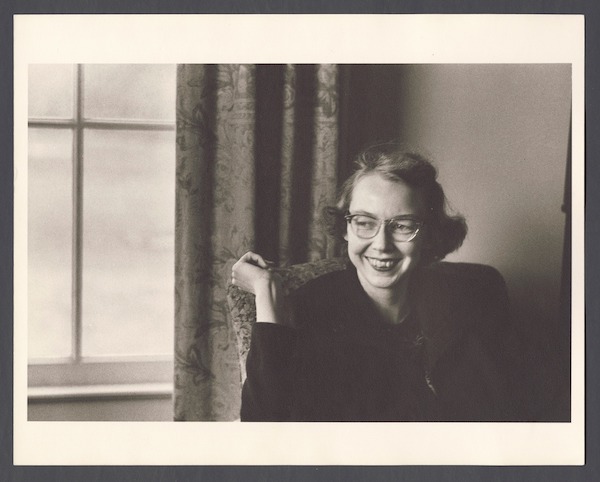

Flannery O’Connor, one of America’s finest writers.

As a long-ago grad student at NYU, I adapted for the stage and directed a one-act version of her masterful short story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” I spent a glorious Caribbean vacation reading and rereading her books, which I’d brought from Boston in my suitcase. I’ve taken a tour of the Savannah house where she was born and, just this spring, drove with my wife, Amy, from Atlanta to Milledgeville, GA, to tour Andalusia Farm, where she wrote her finest work. I stood in front of the Catholic Church that she attended and placed flowers on her grave. Like many of her devotees, I have been longing for a documentary about Flannery O’Connor, one of America’s finest writers.

Flannery, co-directed by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, is certainly worth our attention, for uncovering lots of arresting photographs and an actual TV Q&A with the author, for revelatory interviews with those who knew her, and for the joyfulness of watching other accomplished writers –Alice McDermott, Mary Gordon, Tobias Wolff, Mary Karr — read aloud with the greatest relish from her work. Also, the filmmakers do try to deal with the very complicated issue of O’Connor’s white Southernness and race: her liberal use of the ”N” word “ in her stories, her infamous refusal to meet with James Baldwin at her home in Georgia. Among her stalwart defenders in the film: the African-American writers Alice Walker and Hilton Als. (All of this was before a recent New Yorker article, which showed the depths to which O’Connor was uncomfortable around black people and an avowed segregationist.)

With its many virtues, Flannery isn’t the perfect film biography. It’s a shoot-by-the-numbers conventional PBS American Experience. The filmmakers competently tell the author’s story from birth to death but fail at the harder challenge of getting at O’Connor’s singular, mysterious consciousness. What lurked in the mind of this probably virgin woman living with her mother in rural Georgia, slowly being crippled by lupus, who produced those demonic, Christ-crazy, South-nutty extraordinary stories?

Mary Flannery O’Connor was the coddled only child of businessman Edward Francis and Regina O’Connor, an old-style Southern belle. When she was a teenager, Mary Flannery and Regina moved to Milledgeville, where Regina’s large family resided and where Edward commuted on weekends from employment in Atlanta. When Edward saw his daughter, he encouraged her aspirations to write, something never understood by her mother. In 1941, Edward died of lupus. Mary Flannery attended high school and a woman’s college in Milledgeville, writing eloquently in her diary but known for being a satiric cartoonist in campus publications, perhaps with New Yorker aspirations.

It’s unclear in this documentary how her portfolio led to her acceptance for an MA at the Iowa Writers Workshop. For the first time in Iowa City, Mary Flannery was away from home, shy, lonely, and out of place, teased by the other students for her barely understandable Southern accent. When not in class, she obsessed about her Catholicism and focused on churchgoing as her secular male peers were nightly partying. Fortunately, the faculty led by Paul Engle caught that there was something special in her writing, a unique vision. They greatly encouraged her, even as she battled deep self-doubts. A diary entry: “Dear God, I am so discouraged in my work.… I don’t want to be lonely all my life.”

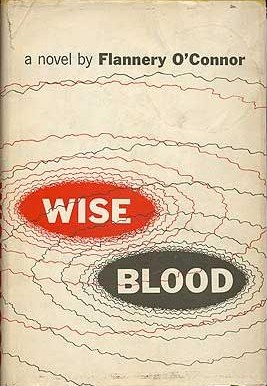

After three years in Iowa, she was accepted for a term at Yaddo, the celebrated writers’ colony in Saratoga Spring, NY, where other Southern writers, Carson McCullers and Truman Capote, had made their mark. While working there on the novel that would be Wise Blood, she became just Flannery, because she decided that the obviously female name Mary could hinder her career.

Her time at Yaddo, as described in the documentary, was packed with nonwriting drama. She got an intense crush on another colonist, poet Robert Lowell, saying in her diary that “He is a kind of Greek to me.” It was unrequited love, though Lowell enlisted O’Connor to help banish from Yaddo the writer Agnes Smedley, because of the political novelist’s alleged Communism. Someone says in the film, “This was not Flannery’s finest moment.”

After that, O’Connor moved to 107th Street in New York, attended Catholic church on 110th Street. At some point, she was taken in by the literary-minded Fitzgerald family: Robert, the renowned translator of Greek texts, and his wife, Sally. She lived in their Connecticut home, and Sally Fitzgerald became O’Connor’s confidante and eventually editor of O’Connor’s letters. Fortunately, the filmmakers of Flannery got to her — she died in 2000 in Cambridge at 83 — for the most valuable interview in the movie. Fitzgerald was witness when O’Connor suddenly couldn’t lift her arms and, convinced that she had arthritis, gave up on Northern living and returned to Milledgeville. It was Sally Fitzgerald visiting O’Connor in Georgia who told the writer the bitter truth: that she was suffering from lupus, which could kill her as it did her father. “Well, that’s not very good news,” said O’Connor.

After that, O’Connor moved to 107th Street in New York, attended Catholic church on 110th Street. At some point, she was taken in by the literary-minded Fitzgerald family: Robert, the renowned translator of Greek texts, and his wife, Sally. She lived in their Connecticut home, and Sally Fitzgerald became O’Connor’s confidante and eventually editor of O’Connor’s letters. Fortunately, the filmmakers of Flannery got to her — she died in 2000 in Cambridge at 83 — for the most valuable interview in the movie. Fitzgerald was witness when O’Connor suddenly couldn’t lift her arms and, convinced that she had arthritis, gave up on Northern living and returned to Milledgeville. It was Sally Fitzgerald visiting O’Connor in Georgia who told the writer the bitter truth: that she was suffering from lupus, which could kill her as it did her father. “Well, that’s not very good news,” said O’Connor.

Wise Blood was published in 1952 to lots of confusion about its grotesque caricatures of devout religious Southerners by an author who was consummately Christian. But O’Connor’s two consequent collections of short stories were much acclaimed and made her famous. Seven days a week, she kept on writing them, never quitting as she became crippled, as her lupus got worse and worse. In the decade before her death at age 39 in 1962, visitors made pilgrimages to Milledgeville, like Katharine Anne Porter and, often, Sally Fitzgerald and her lifetime editor, Robert Giroux, also an excellent interview in the film. And there was one almost-lover, a Danish visitor to Georgia named Eric Langkjaer, who took her for long car rides, and they even smooched. It’s the biggest coup of the film to get Langkjaer to speak on camera, and so openly: “I had a feeling of kissing a skeleton, a reminder that she was gravely ill.” Langkjaer went home to Europe and married, which was devastating to O’Connor, though she claimed in a letter that “I have a spiritual relationship to you.”

What remained? Spirited correspondence with all sorts of people, mostly women, from a liberal pal in New York City to an Atlanta-based lesbian who’d been thrown out of the military for her sexuality. But mostly, it was being a ward of her mother, Regina, who took her to church, cooked her meals, and daily watched over her declining health. My biggest criticism of the documentary, Flannery, is how little this peculiar symbiotic relationship is explored: O’Connor’s living under the thumb of someone who didn’t get her literary endeavors at all. Mother wanted her daughter to write about nice people. She wished her to pen the next Gone With the Wind, a book that daughter disliked. Yes, there should be far more in the documentary about Regina and Flannery, who are, appropriately, buried next to each other in Milledgeville’s Memory Hill Cemetery.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His new feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, is playing at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: documentary, Elizabeth Coffman, Flannery, Flannery O'Connor

Bravo, Gerry. I’m also an admirer of Flannery’s. Even though I don’t have much of a personal experience with the south I think her vision encompasses a whole lot of American life.

Nor am I religious. But she has a way of making the desperation and devastation of social and spiritual matters hit hard, and I really respect her point of view. She’s not selling any snake oil, even if her characters often are.

I think the doc was less paint by numbers– there was the animation, which fit Flannery’s particular skills, and illustrated her stories very well. It’s hard to make an interesting film about a person whose biggest dramas occurred inside herself.

I did NOT like Wise Blood at all when I first read it many years ago. And I’m thinking of going back to it now…

Yes, check it out. I loved the graphic novel version in the movie of A Good Man is Hard to Find. I am not a fan of animation to pep up and perk up and make more “cinematic” an inert documentary, so I did NOT like the rest of the animation, including the sentimental final line animation shot of Flannery on crutches walking away into the distance.