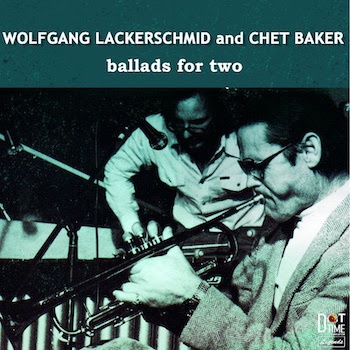

Jazz Album Review: “Ballads for Two — Chet Baker and Wolfgang Lackerschmid”

By Steve Provizer

The trumpeter’s playing on this 1979 album, which would generally be considered as flawed, is part of the singular (mature) Chet Baker gestalt.

Wolfgang Lackerschmid and Chet Baker – Ballads for Two. (Dot Time Records, Legends Series on vinyl)

For about the last 10 years of his life, trumpeter Chet Baker spent a lot more time in Europe than the US. He returned here once or twice a year to perform, but most of his performing and recording was done in France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, or the Netherlands. He recorded with musicians who are probably unfamiliar to most Americans, but they were well-known in their own country including, in 1979, two albums with German vibes player Wolfgang Lackershmid. One album included Buster Williams, bass; Tony Williams, drums; and Larry Coryell, guitar; and this rerelease, a duo recording with Baker and Lackershmid. Baker does not sing on this session, and there are a number of original tunes written by Lackershmid.

The well-known melody of “Blue Bossa,” the Kenny Dorham song, is nowhere to be found in this version. Baker strips the tune to the bone. Lackershmid is busier, but he doesn’t state the melody either. Lackershmid arpeggiates and keeps things moving, while Baker makes use of mostly long tones or slowly moving lines to outline the chords. The trumpet is miked closely and one hears the breathing process clearly. It’s an intimate recording — and an apt description of the performance.

“Five Years Ago” is a Lackerschmid composition. Baker’s trumpet is put through a lot of reverb, which highlights the spectral quality of this sparse melody. Lackershmid uses a cello bow on his vibes in order to achieve a crystalline timbre. After a long slow opening, the tempo increases slightly and Baker becomes a bit more animated. A slow build finally culminates in a run of sixteenth notes. In this way Baker brings the piece to a climax, which then settles back down to a quiet close.

Lackerschmid’s composition “Why Shouldn’t You Cry” starts with Baker’s solo, with the vibes quickly joining in. The tune is constructed along the lines of a standard ballad, but with interesting chord changes. As Baker reaches higher (although not for notes that a trumpet player would consider “high”), the physical effort is evident in the strained sound of the notes. You can also hear the movement of air through the horn, another vulnerable sound. Lackerschmid picks up after this and solos through the tune, using a lot of sustain pedal to create washes. Baker enters to restate the melody, which is compelling enough without ornamentation. Baker’s sound at the close is much “cleaner” than what we were hearing earlier. In one way, this exposes the “dirty” sounds we heard earlier on the performance as mistakes. In another way, it seems unfair to judge this track technically and not strictly on aesthetic terms.

Next is a frequent vehicle for Baker — “You Don’t Know What Love Is” — a standard written by Gene de Paul and Don Raye. This is taken in a more conventional style: a vibes intro, with Baker outlining and elaborating on the melody. Second chorus, Baker starts an improvisation, albeit one that never strays far from the melodic contour of the song. Lackerschmid then takes the lead (not quite a “solo”), with trumpet playing guide tones and slow background lines. Vibes get a bit busier and trumpet, too, picks up the pace. They are listening to one another, but they don’t seem to be following each other all that closely; they are simply manifesting a vague recognition of each other’s sonic energy. Several choruses in, we begin to hear more and more lines that we associate with Baker — mostly middle register, but cleanly played. However, it would have been beneficial for him to have thought to de-spit the horn. The tell-tale gurgle can be heard sporadically — tell-tale to another trumpet player anyway. It may not sour the moment for very many listeners.

Another standard follows, “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise,” written by Sigmund Romberg and Oscar Hammerstein II. Vibes start to state the melody and Baker’s muted trumpet comes in to help out, then to take on the burden fully. There are some moves here by the horn that are pretty unusual for Baker; he seems very invested in taking us deeper into what the chords offer. Vibes take back the solo; Lackershmid’s approach is fairly sparse and non-chromatic. Baker enters to supply light background, then vibes return to the melody and trumpet joins in to close it out.

“Double O” is another Lackershmid original. Vibes initially provide a low, spacious rumble which invites the trumpet to range freely, in a modal fashion. Until a chord sequence alters the approach. A rare double-time kicks in, with repeated notes and staccato trumpet alternating, supplying longer, fluid lines. There’s a slight pause and a return to a new mode, then more harmony shifts with trumpet staying mostly in the low register, which builds up some suspense. The tension is sustained through several fast intriguing changes in mood and a sudden stop.

An introspective reprise of Lackerschmid’s “Why Shouldn’t You Cry” is the final tune. We’re back to muted trumpet here and more reverb. It’s a ballad and, as articulated by Baker, a sad one at that — there’s just a hint of daylight in the bridge. Lackerschmid’s vibes expands the melody somewhat but, again, his soloing strategy tends toward the straightforward. Baker reenters and they bring the out chorus, which is pretty much the same as the original statement, to a stately close.

Baker was at a point of relative stability when this album was recorded. His range and performance energy had decreased, but he plays intelligently “within” himself. He knows what his limitations are and what works. When he pushes the technical envelope, the results are sonically “dirty,” as I described in the first version of the tune “Why Shouldn’t You Cry.” But we don’t listen for “chops” here. Such playing, which would generally be considered as flawed, is part of the singular (mature) Baker gestalt. For me, it’s the mixture of light and darkness in his playing that compels — a puzzle with intimations of gravitas. I listen because I want to try and solve that enigma; I think it may have something to tell me about myself. For others, the beauty is there, self-evident, and powerful enough to overwhelm the “mistakes.”

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Chet Baker and Wolfgang Lackershmid, Dot Time Records

[…] By Steve Provizer, The Arts Fuse […]