Film Review: “The Ghost of Peter Sellers” — A Riveting Postmortem

By Betsy Sherman

The documentary has a “why me?” element to it, with a dark comic edge, but it isn’t a pity party.

The Ghost of Peter Sellers, directed by Peter Medak. Virtual screenings through the Brattle Theatre and the Somerville Theatre.

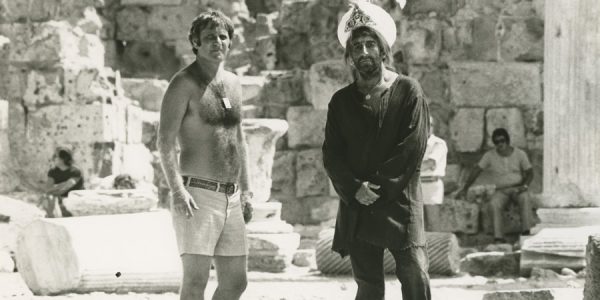

Peter Sellers and director Peter Medak on the set of 1973’s aborted The Ghost in the Noonday Sun.

Some documentaries are about faith winning out over practicality. The Ghost of Peter Sellers is not one of them. The serendipity of this wonderfully anti-inspirational film being released here during 2020 quarantine-times is that it basically says that when faced with an enticing, exotic adventure — sometimes you should just stay home.

The film is director Peter Medak’s postmortem of his unreleased 1973 movie Ghost in the Noonday Sun. A Hungarian refugee who worked his way up in the British film industry, Medak had by that time made a splash: his first three features starred, respectively, Glenda Jackson, Alan Bates, and Peter O’Toole. Then comic genius Peter Sellers, a friend, asked Medak to helm a 17th-century pirate comedy to be shot in sunny Cyprus.

What followed was a nearly career-ending debacle for the director, as, after a trouble-plagued shoot, the movie was shelved by Columbia Pictures. Chief among those troubles was that Sellers, from the time he arrived in Cyprus, pulled every prima donna trick in the book to sabotage the production, from mentally checking out while he was performing to even physically escaping from the island. Forty-plus years later, for this documentary, Medak retraces his steps and ponders what it all meant.

Beyond being a riveting entry for fans of the movie-production-gone-horribly-wrong subgenre — as well as for comedy nerds who ponder the fragility of funny — The Ghost of Peter Sellers has value on a deeper level. It examines memory, friendship, power, the pressures of fame, and underlines the extent to which a director, as Medak says, puts their soul on the line to create a frame of film, no matter how frivolous-seeming the project.

It’s hardly a revelation that Sellers could be a shit, and that he was something of an empty vessel when he wasn’t inhabiting a character. He suffered from depression, as did his partner-in-crime who also figures into this documentary, Spike Milligan (they and Harry Secombe starred in the brilliantly surreal, Milligan-scripted 1950s radio series The Goon Show). But even if you think you’ve heard it all about the star’s bad behavior, stories in The Ghost of Peter Sellers will keep your jaw dropping.

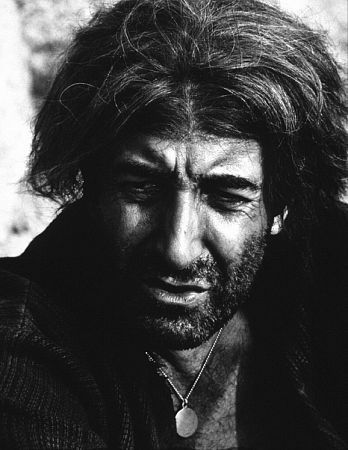

Peter Sellers in The Ghost of Peter Sellers.

In Ghost in the Noonday Sun, Sellers plays a rascally Irish cook who kills the ship’s captain and takes his place on a quest for buried treasure. Medak now admits he was crazy for undertaking a movie set on a ship, having no previous experience of filming on water. He recalls how the pirate ship crashed into a rock wall as soon as it arrived from Athens. Yet on-set photos show the shirtless, shorts-wearing young director behind the camera, beaming with enthusiasm. And he could have soldiered on, through the weather problems, the mechanical problems, and even the sudden presence of the Soviet and American navies in their Mediterranean paradise (an Arab-Israeli war was impending), had the actor who charmed him into taking on the project not completely lost interest in said project.

Sellers was shell-shocked from his recent break-up with Liza Minnelli. On a whim, he fired the two on-set producers. He started a feud with friend and co-star Anthony Franciosa, and grew so fearful of how Franciosa might retaliate in their characters’ swordfight that he refused to share the screen with him. He tried to lead the cast and crew in a labor action to fire Medak, which would be alarming if it hadn’t so closely mirrored one of his early films, I’m All Right Jack, about a factory strike.

Sellers demanded that his old crony Milligan, who had co-written the script, come to Cyprus to act in the film and do rewrites. Medak didn’t realize the extent of the men’s competitiveness; theirs was a love/hate relationship. Milligan’s zany inspirations make for some fun-looking clips, but, according to Medak, they hijacked the already shaky story away from any hope of narrative sense.

Medak, now a white-haired octogenarian, takes the documentary camera on the rounds, gathering survivors of the Ghost in the Noonday Sun production to help sift through the embers. Probably best known for his biting 1972 satire The Ruling Class, Medak really did have a hard time getting back on his feet after the Sellers picture. He made a good haunted house chiller, The Changeling, and rebounded with two excellent British true-crime dramas, The Krays and Let Him Have It. He has worked a lot in television, and has staged operas, but, as he says, the pain of that failed project “never left me.”

In a series of London interviews, Medak collects anecdotes from producers, agents, the costume designer, and one of the few surviving cast members, Murray Melvin. Then it’s off to the Cyprus location. “Haunting,” says Medak of the way it looks essentially the same.

The documentary has a “why me?” element to it, with a dark comic edge, but it isn’t a pity party. Two-thirds of the way into the film, Medak reveals some of his backstory. Born into a Jewish family Budapest in 1937, he and his family survived the war by pretending to be Christian. He learned early on about illusion and the occasional necessity of lies. There were deaths in his family, and the death of his first wife by suicide, that left him accustomed to a feeling of guilt.

Sellers’s vulnerabilities aren’t exactly trivialized. There are clips from an unidentified documentary in which the actor expresses his frustrations. He had a right to be demanding (and defensive) about his career, which at the end of the ’70s reached a new high with Being There, made soon before his death at 54.

Medak finds some perspective among the ancient ruins of Cyprus, and receives reassurance from some of his battle-mates. The dapper producer/financier John Heyman assures Medak that they were all to blame, that it had been far too easy to get a movie funded on Sellers’s name alone, even without a coherent script. And Sellers’s assistant Susan Wood, knowing well her boss’s games, tells Medak with a smile, “you never stood a chance.”

I’ve never seen Ghost in the Noonday Sun (reportedly it was shown on pay-TV in the ’80s). Who knows, it might be a buried treasure. But I have a feeling the anecdote Medak tells in the documentary about being roped into shooting a Benson & Hedges cigarettes commercial in Cyprus is probably funnier than the feature. Sellers was going to receive a Mercedes and envelope of cash (the better to hide it from the tax man) for the spot. Milligan would have a nice payday as well. After the actors performed the slapstick scenario, Medak told Sellers to hold up the cigarette pack for the camera. Sellers said he couldn’t do that. He asked Milligan, who also said he couldn’t do it. What was going on? Sheepishly, they admitted they were both spokespeople for Britain’s anti-smoking charity. Now that’s madness you couldn’t begin to script.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Hi Betsy. Great review! I was the editor of Ghost and I think that this is the best written one yet! You nailed it. Thanks for enjoying all our hard work and all the best from London.