Fuse Commentary: What Survives — The Mad Rush to Digitization

The mad rush to digitization brings up another host of new issues. Unlike a printed book, digital media requires a change of technologies—computers, software, imaging—to interpret the information. Will digitization serve the long-term interests of knowledge as well as the media it is replacing? It’s unlikely.

By Peter Walsh.

When we look back from, say, 2020, 2010 may well be remembered as the year that the printed book, keeper of Western culture since the Renaissance, turned that final corner towards oblivion.

2010 was the year of the iPad (and a host of imitators); the year Amazon sold (it said) more ebooks than hardcovers; the year big box booksellers, old-line publishers, and the New York Times Book Review finally took the digital revolution seriously.

And, unfortunately, that suggests another turning point: the one that leads to oblivion for unknown chunks of our heritage

Why? In the past, radical media change has meant dangerous times for books.

The reason is simple: when media changes, the books people think are important at the time make the transition. Other books do not. And the Darwinian selection of any one moment in time may well not be the one posterity would have wished for.

Consider the Library of Alexander. The great repository of classical knowledge made several major transitions in political regime and one important transition in media: from scrolls to bound codices, what we now call books. The change probably happened around the 1st century AD, when the library was already three or four centuries old and past its glory days.

Hand copying a scroll was expensive and time-consuming. What got copied from papyrus scrolls into books at Alexandria would have been the books most in demand at the time, those the scholars using the library considered most important, and consequently the ones that wore out the quickest.

Unread scrolls would have languished on the shelves and slowly crumbled into dust, probably before anyone even noticed they were gone.

By the 7th century AD, after the Muslim conquests of Egypt, the entire library and all its volumes had disappeared. Even its location is unknown today.

What survived of the Alexandrian heritage were books copied from its collections and preserved in European monasteries and in a handful of royal and private collections. But European readers of the Middle Ages, in turn, were mostly interested in books that related to Christian theology. Latin was the common language of Western literacy. Greek texts, pagan literature, and classical natural science were a much lower priority. Those books weren’t as often read, recopied, or often even collected in the first place. Thus most of the corpus of classical Greek tragedy, for example, once preserved in fine complete editions in Athens and Alexandria and other ancient libraries, vanished from the earth.

Some natural science and medicine later came back into the West via Arabic translations. But much of this, too, was simply lost.

The advent of printing, in the 15th century, brought more losses. Handwritten manuscripts were valued, if at all, as works of art, not records. When Henry VIII abolished the English monasteries, for example, the copying stopped and whole libraries were simply tossed out.

The mad rush to digitization brings up another host of new issues. Unlike a printed book, digital media requires a change of technologies— computers, software, imaging—to interpret the information.

Will digitization serve the long-term interests of knowledge as well as the media it is replacing? It’s unlikely.

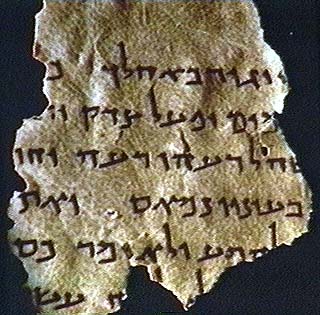

The ability to read cuneiform, probably the world’s oldest written medium, died out around the 1st century AD, just as books came into fashion. But tens of thousands of cuneiform clay tablets survived, buried in the ruins of Mesopotamian cities. When they were dug up in the mid-19th century, scholars were eventually able to decipher them, revealing a history and literature lost for two millennia.

What will archaeologists of ca. 3850 dig up of our own digital revolution? Bits of plastic maybe, but will the bits of data they once contained still be preserved? And would any of the hardware needed to convert that data into words and pictures still be around after 16 centuries?

In a world of instant change and planned digital obsolescence, media pass out of living memory much quicker than any dead language. The hieroglyph for “save this file” on most of my software is a 3 1/2 inch floppy disk, a technology that went out of use a decade and a half ago. I still have stacks of these disks somewhere, stuffed with data, but my current laptop doesn’t even have a drive to read them.

How many computer users today remember what an a-prompt is, or how to access a sub-directory, or do any of the common tasks of the DOS and floppy disk era? And, for all its vast archives of data still lingering, like mine, in boxes somewhere, that era lasted far less than 1% of the time clay tablets did.

Digital, it turns out, is just a lousy way to save things for posterity. David Browne, in a recent Rolling Stone article, writes about “the digital nightmare” haunting record companies. Record company archivists returning to digital files a mere decade or so after they were recorded find much of the music has simply vanished without a trace, probably along with most of the rough drafts, emails, and personal data of what the future will know as our most important men and women.

“Label archivists tell horror stories,” Browne adds, “about receiving hard drives that are blank or filled with unidentified files.”

“That’s the trouble with digital,” Browne quotes Steve Webbon, head archivist of the Beggars Group record company. “When it’s gone, it’s gone.”

“‘You open a session even from 10 years ago, and it might have a plug-in that ‘s not supported, so you don’t have that effect anymore,” complains Greg Parkin, VP of archives at EMI.

According to Browne, at a hearing on the topic, Producer T Bone Burnett, summed it up: ‘Digital is a feeble storage medium.”

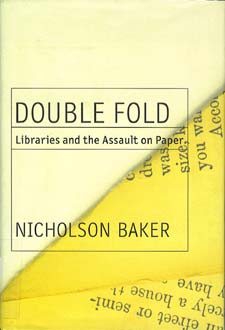

Questioning the headlong rush to new technologies is not new. In a series of New Yorker articles and in his 2001 book Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper, novelist Nicholson Baker mounted a personal Jeremiad against the destruction of paper card catalogues, with their careful hand notations by generations of thoughtful librarians, as digitization took hold.

Later, he railed against the mass disposal of bound newspaper collections in favor of the questionable (in Nicholson’s opinion) advantages of microfilm.

“The Library of Congress and the New York Public Library once owned Pulitzer’s New York World complete . . .” Nicholson writes in Double Fold. “Harvard University, the University of Chicago, the Chicago Public Library, and the Chicago Tribune Company once held complete sets of the Chicago Tribune. They don’t now.”

Nicholson particularly deplores the loss of the experience of a physical newspaper with its elaborate illustrations, lavish color supplements (often works of art in the late 19th century), and the grand scale of the broadsheet page. Microfilm reduces the color to black and while, halftones to murky black squares, and the small newstype, not infrequently, to illegibility.

At best, Nicholson implies, the new technology reduces the intangible meanings of newsprint to mere data. Worst of all, Nicholson says, government subsidies encouraged the rush to microform and the obliteration of the paper originals.

“Not since the monk-harassments of sixteenth-century England,” he argues, “has a government tolerated, indeed stimulated, the methodical eradication of so much primary-source material.”

In 2009 I attended an MIT conference on data storage and media. The attendees tended to fall into two camps: the scholars assumed that someone, somewhere was taking care of all the material that needed to be saved. Digitization, they thought, just made everything so much easier.

The librarians and archivists at the conference—the people in charge of the saving—weren’t nearly so confident. Over and over again, they explained the sheer size of the problem of keeping digital data alive created a mountain of problems.

Introducing the opening plenary for that conference, I pointed out that every document by William Shakespeare’s own hand—all his manuscripts, his letters (there must have been thousands), any notebooks or diaries he kept—had all disappeared. In 17th-century England, the lives commoners were not thought worth recording for posterity.

Over the hundred years that it took to transform Shakespeare, the London media executive and country gentleman, into the greatest writer of all time, almost all the primary source material on Shakespeare’s life was tossed out by someone who thought it was worthless.

Considered mere commercial ephemera by most Elizabethans and probably the bard himself, Shakespeare’s plays were preserved entirely by others, mostly after his death. If they hadn’t stepped in, we might have lost everything.

Besides the poems and plays, what survived of Will’s life, patiently teased out by generations of Shakespeare scholars, were little bits and scraps of his legal life recorded by anonymous scribes in British archives. Only there was the essential chain of preservation maintained. And even then most of the data concerned his physical property and business activities, not his greatest gifts to posterity.

Am I just a latter day Luddite? Not at all. I love ebooks, have read them for years, and carry around about 400 volumes in my pocket. But the prevailing optimism about new media is not going to save our past. Nor will Google or any other corporate entity by itself. We can’t take anything for granted.

As with every other media revolution, what survives is what we take care to preserve.

No, ebooks will not save all of our past but as an author facing a breakdown both of the reviewing and distribution systems in publishing, I’m happy to have another way of reaching readers. Bookstores in most towns have become history and the chains are in the process of closing. So ebooks are the only option, particularly to those of us interested in an international readership.

I translated a memoir from the Czech called Under A Cruel Star by Heda Kovaly. It’s been selling to readers all over the world who can’t get it in their own country but can download it in the US, UK and France. When Amazon ran out of stock on paperback copies, the electronic version kept selling. It was a happy experience in a currently very unhappy industry.

Ebooks aren’t the only option— yet. But in five or ten years, they may have driven all the alternatives into economic oblivion. Physical libraries, which are expensive to run and take up a lot of valuable real estate, may not last much longer. Print-oriented librarians could soon follow publishers, book sellers, newspaers, and critics into the dustbin of forgotten technologies.

My question really is, what then?

One model to look at is the musical recording industry that in my lifetime has moved from 78 rpm records to technologies I don’t even know the names of. In each succeeding wave of updated technologies, old recordings have been remastered and sometimes restored in the manner of museum masterpieces. Of course there are many recordings that don’t “graduate” to newer technologies. I have some of them in my collection of 33rpms that I listen to on my turntable in addition to the CDs (I never got an ipod) I hate to sound upbeat but I think electronic publishing is a good aspect of globalization and is already influencing the artistic end of things in many unexpected ways. Of course, it can be manipulated — as traditional publishing has been. But since the distribution of books has become such an obstacle to both writers and readers (costs of production, transportation, real estate, the collapse of cultural journalism) , what alternative do you see?

My commentary is not about publishing. It is about preservation. Whatever the advantages of digital distribution, digital files are just a terrible way to preserve information for more than five years.

Analog records pressed ninety years ago can still be played on the original equipment without special skills or newer technologies. But, according to Rolling Stone, cannot be played by anyone on any machine on earth. This suggests a problem.

The alternative to losing unknown amounts of our cultural history is to start thinking about the problem now instead of later. My own hope Is that digital technologies will be a very short chapter in the history of media, soon to be replaced by something much better.

But only time will tell.

That should have been “digital files only ten years old cannot be played…”

“Digital is a lousy way to save things for posterity.”

I’m happy to finally hear somebody say it.