Book Review: “The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris” — The Mystery of Art and Love

By Kathleen Stone

Marc Petitjean seamlessly moves from describing intimate scenes to discussing Frida Kahlo’s art and its significance.

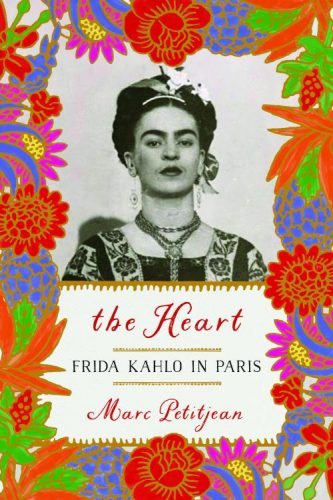

The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris, by Marc Petitjean, translated from the French by Adriana Hunter. Other Press, 208 pages.

The Heart, Frida Kahlo.

Frida Kahlo painted The Heart in 1937. Like much of her work, it is autobiographical. At the center of the picture she stands between two clothes hangers suspended from the sky. On her right hangs a white shirt and dark blue skirt, the school uniform she wore as a girl. On the left is a long flowing skirt and a short huipil top, traditional Mexican attire she later made her signature style. Frida, in the middle, is dressed in a leather bolero top over white skirt and blouse, the kind of clothing she wore early in her marriage. Her body is wounded: left leg swollen, hands missing and heart pierced with a rod. On the ground lies a huge, deep red heart, spilling a trail of blood.

Marc Petitjean grew up looking at this painting in his father’s house. It frightened him as a child and intrigued him as a teenager. But it took on particular personal significance after a Mexican writer approached him for information about his father’s affair with Kahlo. The relationship was news to him, though not entirely surprising given that his father had told him the painting was a gift from the artist. His father had been part of Parisian surrealist circles in the 1930s; for a time he supported Trotskyite political views. Such associations could have explained how he met Kahlo when she visited Paris in 1939. But his father’s past was a mystery to Petitjean; learning about the secretive affair presented a tantalizing opportunity. By examining Kahlo’s life and art, finding out what he could about what happened between them, maybe he would understand more about his inscrutable father. With this in mind, he began The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris.

The book covers two months in early 1939, when Kahlo was in Paris for an exhibition of her art. She was then reeling from news that her husband, the renowned artist Diego Rivera, intended to divorce her. She was still distraught after discovering that one of his infidelities had been with her younger sister. On her own in Europe for the first time, Kahlo was emotionally vulnerable yet determined to use the opportunity to establish herself as an artist.

In fluid, sometimes idiosyncratic prose, Petitjean recreates Kahlo’s experiences. He draws from documented facts, but speculates as well. The narrative’s timeline is fractured, its dynamic flashbacks and digressions effectively reflecting a Paris at the denouement of the Spanish Civil War and on the brink of Nazi occupation. Petitjean, a filmmaker and photographer, brings a visual acuity to his writing, vividly describing color and movement as well as artistic and architectural details. That pictorial sense also informs his insights into Kahlo and her work, which is the book’s impressive accomplishment.

Kahlo was preoccupied during her stay in Paris. Not only was the emotional turmoil from her relationship with Rivera still fresh, but she was disappointed by the pallid reception she and her artwork initially received. André Breton and his family hosted her, but their apartment was cramped and dirty. She resented Breton’s efforts to thrust her into his circle of surrealist artists, whom she found overly intellectual. Even more troubling was the possibility that the solo exhibition she had anticipated was not going to occur. Breton, she complained to friends, never bothered to get her paintings out of customs, and the gallery he had supposedly lined up for the show turned him down. Only when the artist Marcel Duchamp intervened did another small gallery, the one for whom Petitjean’s father worked, agree to show her paintings. Despite this, the solo show Kahlo hoped for was pushed aside. Along with Kahlo’s work, Breton exerted his clout to mount a “Mexico” exhibit of ethnographic objects he had collected during his travels in the country, plus 19th-century portraits and other photographs.

The night before the opening, he imagines Kahlo and his father at the gallery:

Alone on the premises at such a late hour, they unpack the paintings one by one from their wooden crates. Others are already lined up against the wall. They do not turn on the lights, but examine each piece by flashlight. In the surrounding darkness, the paintings appear in this beam of light like radiant windows, almost icons. My father feels as if his eyes are drawn in by the images. They call to him and watch him.

Then we see them alone in the house of Marcel Duchamp’s romantic partner:

I imagine it is cold in Mary Reynolds’s house. They set up a makeshift bed by the fireplace, where they keep a fire roaring the whole time, my father feeding it with great moss-covered logs. Here on this bed they make love, drink, eat, sleep, smoke and spend long hours talking and listening to music. They are not apart for a moment and go out as little as possible, and this brings them together in a deep yet lighthearted intimacy. They know they can tell each other anything, and it will never go any further.

After the senior Petitjean goes out to his part-time jobs at a printing press, he returns early in the morning with a newspaper review of the exhibition that praises Kahlo’s work, noting that it is full of “integrity and illuminating accuracy.” She, still in bed, kicks away the sheets, “revealing her body, then spreads her legs and bends them slowly. Still looking him provocatively in the eye, she throws her arms in the air and cries, ‘Viva la vida!’ The sight of Frida with her legs open, forming an M shape, immediately reminds him of the 1932 painting My Birth that he and André Breton hung in the gallery the day before. He is disturbed by the transition from the artist’s pictorial world to reality. The work itself is difficult to behold and surprised him with the sheer crudeness of what it portrays.”

From this scene Petitjean pivots to a description of the painting, meditating on its place in the artist’s oeuvre. “My Birth marked the conscious starting point for the narrative of Frida Kahlo’s pictorial autobiography, overlaying the real with the imaginary, and the past with the present. From this point on and for the rest of her life she would endlessly reinterpret her own story.” Petitjean is at his best when he provides this kind of illuminating analysis. He moves seamlessly from describing an intimate scene to discussing Kahlo’s art and its significance. He uses this technique repeatedly throughout The Heart, always grounding digressions about her work in what happened — or might have happened –in Paris.

Even when he ventures into more psychological territory, Kahlo’s time in Paris remains the foundation. “One afternoon in the hotel, she is lying on her back naked on the bed with her hair fanned out around her face and resting her head on one arm. My father is sitting on the edge of the bed looking at her. She responds to his gaze: ‘I’m ugly, a walking disaster, my life unfolds as if I should never have existed.’ She then gives him a playful topographical description of the damaged parts of her body, pointing to each scar in turn.”

From this point, Petitjean provides a more general discussion of how Kahlo’s damaged body affected her art. He concludes that,”like other children all over the world, Frida noticed from her earliest days that when she was sick her parents, sisters and friends looked after her, surrounded her with affection, and gave her presents, which made her feel alive and loved and that the world revolved around her. She went on to make abundant use of this form of emotional dependence related to sickness to remedy her depression, her feelings of inner emptiness, and her chronic pain, but also to satisfy her narcissistic impulses.” Her grievously wounded figure in The Heart serves as the key image, suffering as a way to make herself known to the world.

Predictably, Petitjean is not able to unlock all the secrets of his father’s heart. Even with all his thoughtful reconstructions and and research in libraries and archives, crucial questions remain. He tries to answer as many as best he can, but sometimes he must make sense of the unknowable: “Did she specifically want to give him this painting or did he actively choose it among others? Either way, The Heart set a seal on their idyll.”

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her website can be found here.