Television Review: Netflix’s “The English Game” — The Sport of Class Warfare

By Glenn Rifkin

For those averse to sports, The English Game is focused more on attitudes and mores of the time than on the game itself.

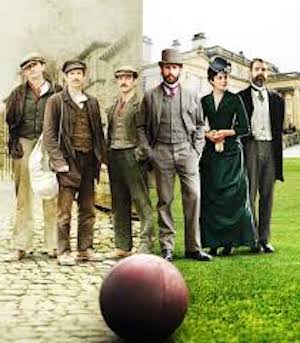

A scene from Netflix’s The English Game.

No one loves a good class struggle more than Julian Fellowes, the Emmy- and Oscar-winning creator of Downton Abbey and Gosford Park. His long and remarkable career as an actor, screenwriter, and producer is marked by his fascination with that tenuous intersection between the haves and have-nots that characterized English society during the waning days of the Victorian era, when the 19th century slipped headlong into the 20th.

In the Netflix series The English Game, Fellowes (along with Tony Charles and Oliver Cotton) takes another look at how the posh and high-born of the British aristocracy encounter, in all manner of snooty resistance, the riff-raff of the working class, this time on the football pitches of Lancashire and London. This six-part series, based on actual events, focuses on soccer’s emergence as that nation’s passionate obsession, at a time when the industrial revolution was remaking the landscape and spawning massive changes for the empire and the game.

The drama, set in 1879, is built upon the clash of two young athletes: Arthur Kinnaird, played brilliantly by Edward Holcroft, as the football-obsessed Eton grad, son of wealthy banker Lord Kinnaird (Anthony Andrews). He is the tough-minded star of the Old Etonians football squad that has already won several Football Association (FA) championships and he aims to keep things as they are; and Fergus Suter, a working-class hero and emerging star who relocates from Scotland to play for pay for a team sponsored by a cotton mill in the impoverished town of Darwen, Lancashire.

Suter, skillfully portrayed by Scottish actor Kevin Guthrie, is the best player in Scotland and he, along with his best friend, Jimmy Love, have remade the game with innovative strategy and unmatched skills. The pair is enticed by mill owner James Walsh (Craig Parkinson) to “work” for him while playing for the Darwen squad, a fiercely proud bunch but lacking the level of talent that could win the coveted FA Cup. Walsh, a fair-minded and passionate entrepreneur, believes that a championship will bring untold levels of joy and pride to the Darwen populace, and he is willing to bend the rules to make it happen.

Netflix’s The English Game.

When Kinnaird and Suter first meet on the pitch in a qualifying game for the Cup, the former embodies the entitled “gentleman” who sneers with pompous glee at this upstart player for whom he has little respect. But when Darwen overcomes a five-goal deficit to tie the game, Kinnaird realizes that a significant shift in fortunes may well be underway. Kinnaird, who would eventually become the president of the FA for 33 years, undergoes a change of heart as the series unfolds, a realization that his “gentleman’s game” was facing an immovable opponent: change, and that resistance was futile.

Suter, for his part, is the proverbial stranger in a strange land, unwelcome to the Darwenians, who resent that he is being paid to play by the mill owner, and detested by the aristocrats who mock his rough, working-class roots. Winning over his teammates proves to be harder than winning on the soccer fields, and his journey to the championship is fraught with painful reminders of the life he left behind in his native country.

For those averse to sports, the series is focused more on attitudes and mores of the time than on the game itself. The football action sequences are perhaps the weakest part of the series. Thankfully, they are brief. Fellowes, whose Downton Abbey bona fides are evident throughout the series, expertly blends in subplots built around the wives and lovers of the main characters, creating multiple story arcs that explore the clash of cultures that marked the era. Kinnaird’s wife, Alma (Charlotte Hope), is the football-widow who isn’t shy about pointing out her husband’s effete arrogance. Childless, the couple struggles to find solace by attempting to reform the cruelties of the underground baby-trade that flourishes in the unregulated dark alleys of the rural villages.

Suter falls in love with Martha Almond (Niamh Walsh), an unwed mother, who labors to remain employed and raise her toddler daughter while hiding the father’s identity in the face of shame and scorn. In other words, this is vintage Fellowes storytelling.

If this excellent series is flawed, it’s because of the overnight metamorphoses of several key characters, who swing from villains to heroes in a flash. But with just six 45-minute episodes, transformations need to happen quickly, both on the pitch and in the tectonic shifts of Victorian England. Accepting that football was inevitably going to become the game of the masses was difficult for some aristocrats. One can’t help but wonder if Fellowes was tempted to take on a contemporary manifestation of football passion: the unfortunate hooliganism that followed in the decades to come, which has tainted England’s beautiful game.

Glenn Rifkin is a veteran journalist and author who has covered business for many publications including the New York Times for nearly 30 years. He has written about music, film, theater, food and books for the Arts Fuse. His new book Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire was recently published by McGraw-Hill.