Opera Album Review: Rossini’s Pre-fab Opera, “Eduardo e Cristina,” Turns Out to Be First-Rate

By Ralph P. Locke

The practice of reusing large chunks of an opera for a new plot and new words may sound implausible to us, but in Rossini’s hands the result is delightful and surprisingly coherent.

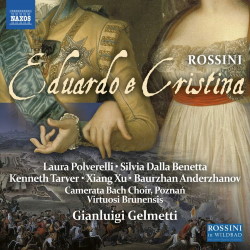

Gioachino Rossini, Eduardo e Cristina (1819)

Silvia Dalla Benetta (Cristina), Laura Polverelli (Eduardo), Kenneth Tarver (King Carlo of Sweden), Baurzhan Anderzhanov (Prince Giacomo of Scotland). Virtuosi Brunensis and Poznan Camerata Bach Choir, cond. Gianluigi Gelmetti.

Naxos 8.660466-67 [2 CDs] 125 minutes

Click to purchase.

Eduardo e Cristina is an oddity among Rossini’s 40 or so operas, having been compiled by him from portions of three of his recent operas. Rossini adjusted the music to fit a libretto that itself was a redo of one that had been set by Stefano Pavesi. The operas from which the bulk of the music derives had not yet been heard in Venice: Adelaide di Borgogna, Ermione, and Ricciardo e Zoraide. Rossini also inserted an aria from Pavesi’s opera. The resulting work—stitched together, though Rossini also engaged in some revising along the way—had its first production in 1819 in Venice, featuring the contralto Carolina Cortesi in the trouser role of Eduardo.

The premiere was an immense success: the poet Byron reported that Rossini “was shouted, and sonnetted, and feasted, and immortalised.” The work soon appeared on dozens of stages across Europe and even reached New York City. But by mid-century, the Romantic conception of the great, unique, integrated work of art began to take hold. Cut-and-paste operas such as this one (the technical term was pasticcio or centone) fell out of the repertoire more or less forever. In our own day, the “Rossini in Wildbad” festival (in Germany’s Black Forest region) has brought it back twice: in 1997 and—the recording here—2017.

The opera takes place in Sweden. The plot is very standard for the period. It features royal princess Cristina (soprano) and military general Eduardo (a trouser or “breeches” role for mezzo-soprano), who are secretly married and have a small child; the king of Sweden (tenor), who is the heroine’s imperious, hotheaded father; and, with less to sing, Prince Giacomo (bass), Eduardo’s rival for the hand of Princess Cristina. In the middle of the opera, Eduardo admits openly his feelings for Cristina but without revealing his identity. The king sends the lovers to prison and threatens them with death. Eduardo, freed by his soldiers and the people, leads the Swedish troops to victory over the Russian invaders. The king, appreciative, recognizes Cristina and Eduardo’s marriage (and presumably goes off to buy their child a rocking horse at Ikea). The opera ends with what opera historians call a “vaudeville” finale of rejoicing, rather like the one in Mozart’s Abduction: the main characters take turns singing more or less the same happy tune, thus closing off the opera in a mood of collective rejoicing.

The practice of reusing large chunks of an opera for a new plot and new words may sound implausible to us. But Rossini’s operas lend themselves to such repurposing: for example, libretti at the time generally used only a few standard verse meters and rhyme patterns. Also, the aria structure of 1) a cantabile followed by 2) a more kinetic transition passage that leads to 3) a cabaletta can be applied to many different situations. In Act 2, for example, we encounter Eduardo, miserable in prison (hence singing a cantabile). In the following, more kinetic section, he is liberated by the soldiers and townspeople and expresses his surprise and delight. This of course then leads him into a cabaletta of patriotic defiance. A fascinating study could be made of how each number in Eduardo e Cristina functioned in the opera from which it was drawn and how it functions in the new work.

Gioachino Rossini

None of this would have been of much interest if the performance here were shabby. But it is often very classy, as those who know previous recordings by Italian-born soprano Silvia Dalla Benetta (Violetta in Verdi’s La traviata is one of her famous roles on stage) and American tenor Kenneth Tarver (a Handel-and-Rossini specialist who got his training at Interlochen, Oberlin, and Yale) will easily understand. I expressed admiration for her when reviewing Bellini’s Bianca e Gernando and for him in Rossini’s Sigismondo and Bianca e Falliero (in American Record Guide, March/April 2018). Benetta is heard at her best at the beginning of this excerpt from Act 2. And here is Tarver combining vocal clarity and thrust with a thrustful delivery of the character’s impassioned words (“O monster!”).

Dalla Benetta’s long notes here sometimes wobble a bit. Tarver lacks strength in the role’s lowest notes, and he sometimes takes high-flying coloratura in full voice, when a lighter delivery would be more stylish. Still, each puts numerous passages across with (as the situation demands) eruptive energy or limpid grace.

Laura Polverelli, as Eduardo, negotiates the coloratura smoothly, but sustained notes are nearly all afflicted with a slow vibrato (as in the beginning of this excerpt from Act 1). As with Tarver, the voice is thin when the role goes low. Still, she sings with spirit, which can carry the listener far even when purely vocal pleasures are few. You can get a good sense of the fine goods on display in this video of rehearsal excerpts.

As in numerous previous recordings from the “Rossini in Wildbad” festival, the Moravian-based orchestra plays solidly and sometimes quite beautifully (especially the solo woodwinds), and the Polish chorus is just as fine, as in this atmospheric passage from Act 2. (In addition to my reviews listed above, I reviewed in American Record Guide recent Wildbad recordings of Rossini’s early Demetrio e Polibio, his aforementioned Aureliano in Palmira, and his Maometto II.) Rossini veteran Gianluigi Gelmetti, at age 72, conducts spiffily, maintaining good balances, adjusting tempi considerately (except on some particularly demanding coloratura passages, where he could have been more flexible without losing dramatic momentum), and shaping phrases in a musicianly manner. Applause has been edited out except at the ends of the acts.

The cast of Eduardo e Cristina with conductor Gianluigi Gelmetti (in the middle). Photo: Andreas Kühn.

There is only one previous recording of this not-quite-original but beautifully crafted opera. It was made during the 1997 production, likewise at the Wildbad festival. Charles Parsons (in American Record Guide) found the singers adequate at best. That recording, on Bongiovanni, is no longer available.

The new release, from unstaged performances at the festival, is clearly preferable. I recommend it highly to anybody interested in getting to know the lesser-known Rossini operas, which tend to be as polished and fascinating as the ones that we know and love. It is available through the usual subscription-streaming services (such as Spotify), and, broken into numerous shortish segments, for free on YouTube.

One tiny regret: the aria by Pavesi that Rossini incorporated has been excluded, perhaps because somebody at the festival had a lingering sense that a borrowed aria is an intrusion, even in an opera that is, in a sense, all-borrowed. I’d have liked to hear it.

The booklet essay is much less informative than was Bongiovanni’s, which (Parsons reported) contained a detailed chart showing which items in the score were borrowed, where each came from, and which items were newly composed by Rossini. Naxos provides a libretto online, but—drat!—in Italian only. The Bongiovanni booklet (maybe you can find a copy in a library?) included an English translation.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. He contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Thanks for another informative article by Ralph Locke. I was glad to learn more about this opera and the tradition of cut-and-paste operas, a tradition that might not be well-known today.