Opera Review: Beyond the “Barber of Seville” — New Recordings of Two First-Rate Forgotten Operas by Rossini

By Ralph P. Locke

Beethoven reportedly told Rossini to stick to writing comic operas. But new recordings of two of Rossini’s major serious operas bring great pleasure to the listener—and let us hear some splendid young singers.

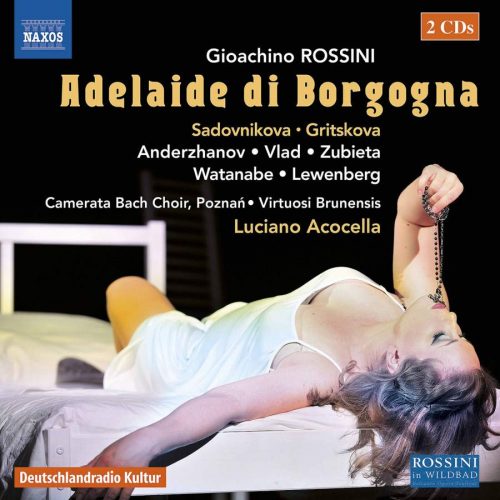

Rossini: Adelaide di Borgogna

Ekaterina Sadovnikova (Adelaide), Margarita Gritskova (Ottone), Gheorghe Vlad (Adelberto), Baurzhan Anderzhanov (Berengario), Miriam Zubieta (Eurice), Yasushi Watanabe (Iroldo), Cornelius Lewenberg (Ernesto)

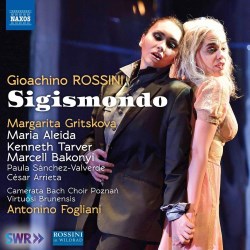

Rossini: Sigismondo

Maria Aleida (Aldimira), Margarita Gritskova (Sigismondo), Kenneth Tarver (Ladislao), Marcell Bakonyi (Zenovito and Ulderico), Paula Sanchez-Valverde (Anagilda), César Arrieta (Radoski)

Virtuosi Brunensis, Camerata Bach Choir Poznan, conducted by Luciano Acocella (for Adelaide di Borgogna) and Antonino Fogliani (for Sigismondo)

Adelaide: Naxos 8.660401 [2CD] 123 minutes.

Sigismondo: Naxos 8.660403 [2CD] 149 minutes.

Here are two largely unknown serious operas by Rossini, each recorded at a set of performances at the annual Rossini summer festival in Bad Wildbad, a town located in the Black Forest region of southwestern Germany. Adelaide di Borgogna was recorded in 2014; Sigismondo, in 2016. Both works were rarely performed in Rossini’s own day. I had not encountered either one before listening, but I am delighted now to have gotten to know them.

Adelaide di Borgogna (1817) takes some basic facts from medieval history and adapts them to the norms of early nineteenth-century Italian serious opera. The main soprano role is Adelaide, the widowed queen of Burgundy, whose husband had gained control of much of Italy and then got murdered for it. Two men struggle over her: the virtuous—which is to say, in more sober historical terms, politically and militarily effective—Ottone (i.e., Otto, the Holy Roman Emperor), played by a mezzo-soprano, and the villainous Adalberto (Adalbert, son of the rebellious Italian nobleman Berengar, the latter here called Berenagario), played by a tenor.

Thanks to some determined scholars, Adelaide di Borgogna has been revived at three major festivals devoted to forgotten Italian operas of the eighteenth and/or nineteenth centuries. Desmond Arthur (in American Record Guide, January/February 1994) praised Adelaide when reviewing the CD release of a recording from the first revival, which had taken place ten years earlier, at the 1984 Valle d’Itria Festival: “Rossini’s musical inventiveness even under [time] pressure was inexhaustible, and there are highly effective solo scenes and duets and a couple of grand ensembles and finales.” He found, though, that only one singer was fully capable: Martine Dupuy, in the trouser role of Ottone. Charles H. Parsons, reviewing the Arthaus DVD of a more recent performance—from the Rossini Festival in Pesaro—said the music “is prime Rossini. Yes, it sounds rather appropriate for a comic opera, but what a wealth of tunes.” He declared that the Ottone (Daniela Barcellona) “sings like a goddess,” and he appreciated the rest of the performers, notably Jennifer Pratt (in the title role) and the conductor, Dmitri Jurowski (September/October 2014). He described the production as interestingly updated and “a video extravaganza.” (There is also a CD recording from a concert performance in Great Britain: see below.)

The present CD recording, from the aforementioned “Rossini in Wildbad” festival, is also available as a Blu-ray DVD, which I have not seen. As the notes carefully explain, three short arias for secondary characters in the opera may not have been written by Rossini himself, and one of them is omitted here (presumably no great loss).

The Haydnesque overture will be familiar to many listeners from its use in Rossini’s very first opera, the delightful one-act La cambiale di matrimonio. Adelaide’s final aria includes a chunk of an aria, “Cessa di più resistere,” that Rossini had composed for Count Almaviva to sing toward the end of The Barber of Seville (February 1816). “Cessa,” extremely virtuosic, was quickly suppressed in most performances of Barber, so Rossini felt free to place materials from it in other works. (The cabaletta went into La cenerentola, for the title character’s final aria.) But numerous delightful numbers here will be quite new to most listeners, including duets for the three main characters in their three possible permutations, and an elaborate quartet for the same three plus the rebellious Berengario.

The performers have the style under their belts: tempos are fleet, if somewhat inflexible, and voices in most of the major roles are young and firm. One exception: the Berengario, from Kazakhstan, possesses a voice that is too thick for this repertory, and his sense of pitch is not clear enough.

This was my first time encountering Ekaterina Sadovnikova (soprano) and Margarita Gritskova (mezzo), both from Russia, Miriam Zubieta (from Spain), and Gheorghe Vlad (tenor), from Romania. Gritskova, in particular, manages to toss off the florid writing with precision and grace, and also to seize moments in which to vary the tone (e.g., by a momentary swelling or pulling-back). Sadovnikova and Zubieta likewise bring lift and light to Rossini’s lines. Vlad is a mixed blessing here. His voice’s basic quality is lyrical and sweet, but the low register is weak and coloratura is often smeared. Vlad does, though, pull off a lovely soft trill in his aria.

The chamber orchestra from the Moravian city of Brno (in the Czech Republic), sounds alert under Acocella, with just an occasional moment of imprecise tuning. The chorus, from Poland, is small but responsive. The sound is clear, never overloaded. In the final minutes of Act 1, I wished the tempo were just a shade slower, so the voices could allow each note to “sound” a bit more fully. Instead, we get a welter of consonants articulated rhythmically. But, other than that, I think the opera is well represented here.

I was feeling quite enthusiastic about this recording until I learned of another CD recording that is available (Opera Rara 32), from a 2005 concert performance in Edinburgh, conducted by Giuliano Carella. This is on 2 discs, full-price. A newspaper review of the concert itself specifically mentions Bruce Ford’s Adelberto as “compelling,” which one cannot say about Vlad’s for Naxos. And it describes Jennifer Larmore (as Ottone) and Marjella Cullagh (Adelaide) as “flinging out their music with a combination of thrilling abandon, perfect control and dramatic exactitude.” I’ve sampled the Opera Rara recording and find it superior to the otherwise very capable Naxos-at-Wildbad recording in most respects: more vividly recorded, with a better tenor (as mentioned), and with welcome tempo adjustments to suit the words and the musical sense. And, if you are looking for a video version, the Arthaus DVD mentioned earlier, starring Barcellona, Pratt, and tenor Bogdan Mihai, is most likely preferable to the DVD version of this Naxos CD set. Still, on CD, the Naxos recording remains a reliable and inexpensive way to get a sense of the riches that Adelaide di Borgogna has to offer. It also makes me eager to hear the three main female singers again in other roles.

Sigismondo was first performed in 1814, and thus precedes most of the operas mentioned above by two or three years. Still, it is no early work: it was Rossini’s 14th (out of 39). The libretto is full of complicated machinations that, in the opinion of opera historian Richard Osborne (in Grove/OxfordMusicOnline), make it Rossini’s “most unrevivable serious opera.”

Sigismondo was first performed in 1814, and thus precedes most of the operas mentioned above by two or three years. Still, it is no early work: it was Rossini’s 14th (out of 39). The libretto is full of complicated machinations that, in the opinion of opera historian Richard Osborne (in Grove/OxfordMusicOnline), make it Rossini’s “most unrevivable serious opera.”

Well, that’s a challenge if I’ve ever heard one, especially given that some of the music is so good that Rossini decided to use it again in works that became much more successful, such as Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, La cenerentola, and, yes, The Barber of Seville (passages in the opening scene for men’s chorus and in Basilio’s crowd-pleasing “calumny” aria).

The opera’s lack of performances is often attributed to what at first seems like a libretto filled with implausibilities. In truth, though, the libretto was at once forward-looking and deeply rooted in literary tradition. Briefly, Sigismondo, a king in medieval Poland, has allowed himself to believe accusations made by the courtier Ladislao about Sigismondo’s wife, Aldimira. He has ordered her killed, but instead she—without his knowing—is set up in a modest woodlands cottage. (I will not report here the full extent of the various characters’ devious doings, switches of loyalty, and doubts about their next course of action.)

Sigismondo’s frequent baffled outcries make him a highly specific, almost anti-heroic figure, and in that sense typical of the nascent Romantic movement (with Goethe’s Werther and Büchner’s Woyzeck). But Charles Jernigan, in the booklet-essay, rightly notes that the plot bears a resemblance to certain ancient Scandinavian ballads and to an episode in Ariosto’s sixteenth-century epic poem Orlando furioso. I would add that there are some parallels in plays of Shakespeare, too: the all-too-credulous title figure in Othello and the harsh Leontes in A Winter’s Tale, both of whom condemn, in different ways, a devoted and innocent wife. And, of course, the libretto also systematically inserts arias, duets, and larger ensemble-scenes whose shape and expressive content will feel very familiar to listeners who know other Italian serious operas of the day.

Sigismondo has had one previous and very notable recording: a performance with extremely capable singers—including mezzo Sonia Ganassi, a thrilling presence at age 19—and a student orchestra (in Rovigo, Italy). The performers are all clearly energized by the conductor, the highly experienced Richard Bonynge. After listening to that recording, Charles Parsons (in, again, American Record Guide) was smitten: “I have completely fallen in love with this opera. Such a wealth and variety of beautiful melodies! Original, imaginative, even startling touches abound . . . [and a] delicate interweaving of the voice parts” (March/April 1995).

The novel features of Sigismondo are worth stressing. The title figure’s frequent attacks of semi-madness make him resemble in various ways Assur in Rossini’s Semiramide (written nine years later), Elvira in Bellini’s I puritani (a full twenty-one years later), and (since he thinks he sees Aldimira’s ghost) Donizetti’s Lucia and Verdi’s Nabucco and Macbeth. At such moments his musical phrases are often highly fragmentary and irregularly phrased, and are commented upon by onlookers. The second musical number (not counting the overture) is entitled, by the librettist, “Cavatina di Sigismondo con interruzioni”: “Entrance Aria for Sigismondo, with Interruptions”! As the opera goes on, one can empathize with Sigismondo’s bafflement, given that Aldimira returns to court in disguise as Egelinda, the (very similar-looking) daughter of Sigismondo’s faithful Polish courtier Zenovito.

Sigismondo contains several tuneful, florid duets. The splendid Act 1 finale contains a moment of simultaneous reflection for all the main Polish characters, reacting in part to news of the imminent invasion by the Bohemian army. In the wonderful Act 2 quartet, the fourth character is the King of Bohemia, who has invaded Poland (and who is Aldimira’s father, hoping that the woman named “Egelinda,” whom is now encountering, is, as he suspects, his daughter). At the opera’s end, Sigismondo is brought back to his senses, in part by the threat of military invasion, he mercifully condemns the evil Ladislao to prison rather than death, and father and daughter—Ulderico and Aldimira—are happily reunited.

A scene from a German production of “Sigismondo.” Photo: picture alliance / dpa / Patrick Pfeiffer.

Aside from Sigismondo’s often disturbed soliloquizing, there is much that is typical for its day. The three main roles are, once again, a soprano, a mezzo (singing the main male role), and a tenor villain (the rumor-monger Ladislao). Some of the numbers are utterly exquisite, such as Aldimira’s cavatina (i.e., entrance-aria) in Act 1, which shows attractively varied writing for wind instruments. Refreshingly, offstage hunting horns interrupt Aldimira’s subsequent conversation (in secco recitative) with Zenovito, who is sympathetic to her plight. The evil Ladislao also gets several chances (gratifying for singer and audience) to rue, briefly, having spread his calumnies and to consider his options. And Zenovito’s short aria has a rather amazing solo passage for double-bass. My favorite number is the Act 2 duet for Sigismondo and the disguised Aldimira, in which they express astonishment and a number of other sudden emotions through quick spurts of coloratura, in alternation and simultaneously.

The performance uses the critical edition prepared by the Fondazione Rossini in Pesaro and seems, if anything, more consistently excellent than the Adelaide of two years earlier, from the same Wildbad festival. This time the singers are uniformly accomplished. There is not an Italian among them—they come from places as varied as Cuba, Hungary, Russia, Spain, the USA, and Venezuela—but they all sing in perfect Rossinian style, with a command of coloratura that ranges from capable to supernatural. The tenor is the veteran Kenneth Tarver, a tenore di grazia well known from many recordings (including numerous works by Mozart and Berlioz, and, twenty years ago, Bernstein’s A White House Cantata) and as the title character in a remarkable DVD of Handel’s Belshazzar conducted by René Jacobs. His voice has gained depth and thrust but can still negotiate coloratura with some ease. The Sigismondo is Margarita Gritskova (who was the Ottone in Adelaide in Borgogna), here showing her dramatic range, not just her fabulous singing skills. An excessive wobble appears in the opening minutes of the first-act finale; it becomes less prominent later on, as (presumably) the voice warms up more.

The put-upon soprano is here Maria Aleida, radiating goodness in every note and singing some extremely high notes without strain. Marcell Bakonyi takes two roles very effectively—Zenovito and the King of Bohemia (Ulderico)—though his low notes are weak. Paula Sanchez-Valverde and César Arrieta are a delight to the ear in the smaller roles of Ladislao’s sister Anagilda and his confidant Radoski.

The orchestra and chorus sound even more involved in the proceedings than they did two years earlier (in the Adelaide recording). The conductor is Antonino Fogliani, who has been music director of the Wildbad festival since 2013. Despite the change in conductors, there is once again, as in the Adelaide, a moment (here the climax of no. 16, the 9-minute Quartet for the three main characters plus the Bohemian king) when everyone is getting excited and the music is zipping along, the voices emphasize consonants, and we lose a sense of a steady stream of vowel-carried tone. I suppose that this is an almost-inevitable downside of recording during performances rather than under calmer studio conditions. If so, the disadvantage is small, compared to the advantages of the excitement and vividness that mark the set as a whole. The sound quality is always clear, never either harshly close or—somewhat the opposite—echo-ridden. Occasionally a singer will be too far from the microphone for a few measures (Tarver in the Act 1 finale, no. 9).

Margarita Gritskova as Ottone in a 2014 production of “Adelaide Di Borgogna.”

I strongly recommend Sigismondo to listeners, either in the present recording or the Bonynge, apparently still available from Bongiovanni as CDs or download. I have sampled the Bonynge (on YouTube), and it is indeed as fine as the Naxos: the singing in all the excerpts that I heard is smooth, and Bonynge is readier to slow down and caress a phrase than is Fogliani. Either recording may be preferable to the (more expensive, of course) DVD of a 2012 production at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, featuring Daniela Barcellona and Olga Peretyatko, in which, according to Robert J. Farr’s detailed review at MusicWeb-international.com, the highly conceptual staging confuses and annoys, the Ladislao (Antonino Siragusa) has an unpleasant edge, and Michele Mariotti conducts stodgily.

However one chooses to encounter Sigismondo, the news is that the work is eminently revivable. Take that, Grove!

Let me add a special word of appreciation for fortepianist Michele d’Ella, who, in both recordings under review here, supports the recitatives superbly, sometimes choosing to reintroduce, briefly, a phrase from a preceding musical number and thereby gently reminding us of that the musical element largely predominates over the dramatic in these works. Schopenhauer said something of the sort about Rossini’s operas: that the music often has its own coherence, independent of the plot and sung the words, and that this can be a good thing. After listening to these two operas, I am inclined to agree. Sigismondo, especially, seems a major find. And maybe I’d be saying the same about Adelaide di Borgogna if I were reviewing the Opera Rara recording with Larmore, Cullagh, and Ford.

For both operas, a libretto can be easily downloaded at the Naxos site. It includes track numbers and, very helpfully, gives the text of some recitative passages that we do not hear: presumably any that have been trimmed in the performance, plus the many in Adelaide that Rossini chose not to set. The Sigismondo libretto even gives the text of an alternate duet for the title character and Aldimira that is (sensibly enough) not performed. Alas, both libretti are given in Italian only. Still, the introductory essays and the detailed synopses (with helpful track numbers) may be enough for most listeners.

(The present article is a lightly revised version of a record review that first appeared in American Record Guide and is used here by kind permission.)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book.

Tagged: Adelaide di Borgogna, Ralph P. Locke, Rossini

As a great lover of traditional opera I must say that the music stays great and unbelievably beautiful but… new and modern performance practices on stage are ridiculous !!!!!! How is it possible to reset a medieval play in a modern mise en scene? The music loses its beauty and signification. The mix-and-match does not fit together. Rossini had no intention that this should be done. He wrote the music for a story in the medieval period — no time else.

[…] others were by Rossini, including Adelaide di Borgogno and Sigismondo (which I reviewed, together, here), Zelmira (here), Edoardo e Cristina (here), Moïse et Pharaon (here), and Aureliano in Palmira […]