Opera Album Review, Oscar Wilde, Part 3 — A Spiffy “The Importance of Being Earnest”

By Ralph P. Locke

Odyssey Opera revels in the glittering wit and touching moments of this full-length chamber opera by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, better known for his Hollywood film scores and some wonderful guitar pieces.

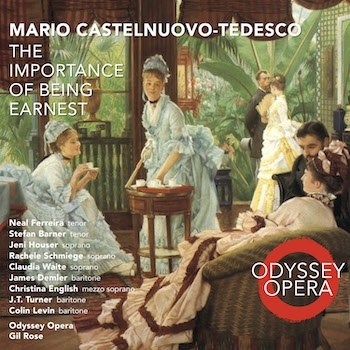

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: The Importance of Being Earnest (opera, after Oscar Wilde)

Rachele Schmiege (Gwendolen), Jeni Houser (Cecily), Christina English (Miss Prism), Claudia Waite (Lady Bracknell), Neal Ferreira (Jack Worthing), Stefan Barner (Algernon), James Demler (Rev. Chasuble), J. T. Turner (Lane), Colin Levin (Merriman).

Odyssey Opera, cond. Gil Rose

Odyssey Opera OO1003 [3 CDs] 148 minutes

The opera world is experiencing an explosion of interest in forgotten works. Some of these works are from the distant past. The Met has enchanted audiences with numerous Handel operas over the past few decades, thanks in part to such marvelous singers as soprano Natalie Dessay and countertenor Iestyn Davies. An equally distinguished house, the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, has recently revived an opera from around Handel’s time: Vinci’s Siroe re di Persia (see my review).

Other works now reaching the opera stage are unfamiliar because they are relatively new, having been commissioned by one opera house and then often getting performed for audiences elsewhere. For example, Mexican composer Daniel Catán’s enormously effective Spanish-language opera Il postino (based on the 1994 Italian-language film), was first seen at Los Angeles Opera, with Plácido Domingo as the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, and then presented in Paris and—this past Fall—by Virginia Opera (in Fairfax, Norfolk, and Richmond).

Less often mentioned are unfamiliar works that are neither old nor brand-new but from the more-or-less recent past. A year or two ago, Gottfried von Einem’s brilliant 1971 operatic version of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s play Der Besuch der alten Dame (The Old Lady’s Visit) was rereleased on CD—see my review—and, almost simultaneously, got a new production in Vienna.

Boston’s renowned and adventuresome Odyssey Opera (whose fascinating 2019-20 season consists of six operas or operettas that all take place in Tudor England) has now released a recording of a wonderful but unfamiliar opera, The Importance of Being Earnest, by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968), that, like von Einem’s opera, was completed a few decades ago. Importance (completed in 1962) is based closely on Oscar Wilde’s much-performed drawing-room comedy of the same title. And (heavens be thanked!) the composer set it in English rather than, as with Strauss’s Salome and some other Wilde-based operas, in translation. (See my reviews of the German-language settings of Wilde’s A Florentine Tragedy by Alexander von Zemlinsky and by Richard Flury.) This Importance opera was first performed a few years after the death of the composer: in a Radio Italian broadcast (1972) and then, staged, in New York City (1975) and in the composer’s hometown, Florence (1984; this, like the 1972 radio broadcast, used the composer’s own Italian translation). And then it fell off the map, until now.

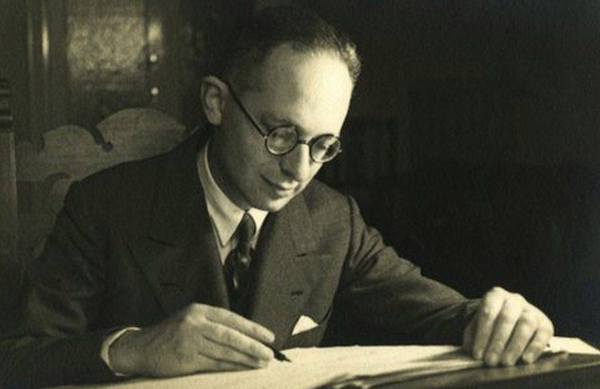

Castelnuovo-Tedesco was an Italian Jew who fled Mussolini in 1939 (at age 44) and made a new home in California, where he became a prominent composer, contributing to over 200 Hollywood films. (His involvement often went uncredited, as on the 1941 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. For a full list, see his official site.) Today he is best known for some marvelous works for guitar, such as the Omaggio a Boccherini, which includes this perfectly crafted minuet. His Violin Concerto No. 2, subtitled I profeti (The Prophets), was commissioned and recorded by Jascha Heifetz and has received several further recordings since then (e.g., by Itzhak Perlman, with Zubin Mehta conducting).

Castelnuovo-Tedesco was a prolific composer in many other genres: piano music, art songs, orchestral overtures inspired by Shakespeare plays, and no fewer than seven operas that vary in length and in degree of seriousness. Musicologist Nick Rossi (in Oxford Music Online) comments that, in them, his “vocal writing suggests a post-verismo lyricism and his orchestral writing a post-impressionistic harmony.” Rossi also points out that the composer, who assembled the librettos himself, often treated his literary sources too respectfully, neglecting to create passages of text that would permit a given character to express her- or himself in an aria (or aria-like monologue).

This turns out not to be a problem in The Importance of Being Earnest.

(I will assume that my readers have some sense of Wilde’s wonderful 1895 play, whose subtitle is A Trivial Comedy for Serious People. If you haven’t seen the classic 1952 film of it, featuring Edith Evans and Margaret Rutherford as Lady Bracknell and Miss Prism, I urge you to repair that omission quickly. YouTube has it entire, with subtitles so you won’t miss a single arch remark or precious jab. There was also a somewhat updated 2002 remake, with Judi Dench, Colin Firth, Reese Witherspoon, and other notables. Wilde’s full text is out of copyright and therefore easily available online. The plot is nicely summarized in Geoffrey Wieting’s review of the staged performances that preceded the recording under review.)

Jeni Houser (Cecily Cardew) and Stefan Barner (Algernon Moncrieff) in the Odyssey Opera production of The Importance of Being Earnest. Photo: Kathy Witman.

I said that the lack of arias is no problem here, because nearly everything that one might want to know about these variously selfish and daffy characters is present in the witty dialogue that Wilde has confected for them. We do not want to hear the inner thoughts of the two pairs of lovers, who are presented as too shallow and self-serving to merit our empathy. And Lady Bracknell, one of the all-time great creations for the stage, reveals her essence with every reproach that she offers to this or that young person in her proximity. Jack Worthing, who wishes to marry Lady Bracknell’s daughter Gwendolen, calls her a Gorgon and asks his friend Algernon: “You don’t think there is any chance of Gwendolen becoming like her mother in about one hundred and fifty years, do you?” To which Algernon famously replies: “All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That’s his.” (Castelnuovo-Tedesco trimmed much amusing banter from the play—for example, Jack’s further comment on the Gorgon image: “I don’t really know what a Gorgon is like, but I am quite sure that Lady Bracknell is one. In any case, she is a monster, without being a myth, which is rather unfair.”)

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s most original decision is to surround these characters with quotations from more than 50 compositions well known to lovers of concert music and opera. He chooses bits that suit the mood or situation, sometimes quite pointedly. For example, we hear music from the judgment scene in Verdi’s Aida (in which the ancient Egyptian priests accuse Radames of treason) when Lady Bracknell is interrogating Jack about his intention to marry her daughter Gwendolen. The spat between Gwendolen and Cecily (who briefly think they are each engaged to the same man) is enacted through excerpts from Rosina’s aria “Una voce poco fà” (from The Barber of Seville—at 7:00). And large chunks of a Bach chorale prelude (“Wachet auf”) accompany, and even are sung by, Miss Prism and Reverend Chasuble in their successive scenes of hesitant courtship, creating quite a touching effect, given their mutual hesitancy and awkwardness. The Bach quotations that underpin their scenes together add depth and gravity to characters who otherwise might have seemed merely repressed and a bit dotty. Put another way, such moments in the music go some way toward making up for any lack of arias or, for that matter, expansive duets.

Two other motives that recur throughout the work are definitely by Castelnuovo-Tedesco. We encounter them in the opera’s dexterously constructed overture. The first motive is busy and chattering. The second—romantic in the manner of a 1950s popular ballad—features a rising figure on the degrees 1 2 3 5 and, immediately after, on the degrees 1 2 3 #5; the result is a yearning melodic surge (in the tune’s top notes, 5 to #5) that makes the whole phrase appropriate for moments when Jack talks of Gwendolen or when the latter appears on stage.

Composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.

Intriguingly, all these dozens of themes and motives get not just restated but often significantly altered, in a manner familiar from standard compositional practices of the previous two centuries (e.g., in a sonata-form development section, or in the constantly churning orchestral tissue in Wagner’s Ring Cycle). Thus, the chattering motive from the overture gets slowed down in portentous manner as Act 1 comes to an end and we realize that Algernon is cooking up a plot that will play out in Act 2. (He will show up at Jack’s country house pretending to be Jack’s nonexistent brother Ernest. You have to read the crucial stage directions, as you listen, to get what is going on.)

One warning is necessary: the opera maintains a slightly slower pace than does the spoken play. Part of this comes from the composer’s evident desire to set the text in a manner that helps the singers enunciate the text clearly and sonorously. Even though he limits the instrumental accompaniment to two pianos and (quite varied) percussion, a voice needs to let each syllable “bloom” lest the vocal line become a gabble of consonants. The other main contributor to the slower pace (or, more accurately, the less rapid pace) comes from all the added orchestral commentary. The net result is a bit odd, but delightful in its way, and I think the opera (which finally got published in 2018) will find frequent performances, perhaps in smallish halls where the singers need not worry about “carrying” to the back rows and therefore can focus on keeping things light and forward-pressing. This Importance would be a perfect item for a university or music-school opera studio. (It occurs to me that the brief orchestral commentaries after many vocal statements nicely allow any audience laughter—of which there will be much—not to obliterate the next vocal entrance.)

The recorded performance helps a lot, since the singers have clear, relatively steady voices, and they enunciate their words with great clarity. Some of this can be sensed in this video trailer of the stage production; or in a separate video trailer that contains rehearsal bits plus illuminating comments from the conductor.

The strongest performer in the cast is Claudia Waite—officially a soprano, but, gosh, she has a full low register!—in the plum (indeed, plummy) role, of Lady Bracknell. I also particularly enjoyed soprano Jeni Houser, bright and smooth as the innocent (but not for long) Cecily; baritone James Demler as Reverend Chasuble; and tenor Neal Ferreira as Jack. Any time Ferreira got a chance to soar high, his voice gave special pleasure. In short, the performance is as strong in its own way as the Radio Italiana one from 1972 (in Italian) that can be heard in its entirety on YouTube. (That cast included the renowned tenor Alvino Misciano.) The CD recording is in the right language—which matters a heap with a master like Oscar Wilde—and comes with a fine booklet essay and the full libretto (including the crucial stage directions), plus some evocative photos of the staged production (at Boston Center for the Arts’ Calderwood Pavilion) that preceded the studio recording (made in WGBH’s Fraser Hall). The sonic quality is fine, with the two pianos and percussion registering well, though occasionally the microphones feature the pianos a bit too prominently.

Neal Ferreira (Jack Worthing) and Claudia Waite (Lady Bracknell) n the Odyssey Opera production of The Importance of Being Earnest. Photo: Kathy Witman.

I hope that the singers remain devoted to bringing unfamiliar works to us. The future of opera depends on our being aware of the many varied ways that music and character/words/drama can interact. Even the (wondrous) works that we get to see and hear all the time do not remotely exhaust the possibilities. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s chamber opera is a one-of-a-kind, and I hail Odyssey Opera for letting us discover it. Indeed, you’ll find it easy to discover, since it can be streamed from various online sources (such as Spotify or YouTube).

An afterword to this now-completed series of three reviews of Wilde operas: In addition to the three operas I have discussed, and of course Richard Strauss’s Salome, there is a lesser-known Salomé (1908), in French, by Antoine Mariotte, which has been performed again in recent years; a version of the short story The Birthday of the Infanta, retitled Der Zwerg (The Dwarf; 1922), by Zemlinsky; Lowell Liebermann’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1999); Malcolm Williamson’s adaptation of the fairy tale The Happy Prince (1965); and a ballet based on the same tale, with music by Christopher Gordon and choreography by Graeme Murphy (2019). Plus there are various musical comedies freely based on Wilde plays, such as Noel Coward’s After the Ball (deriving from Lady Windermere’s Fan). And, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, the self-bedazzled Reginald Bunthorne is a satirical version of any one of several poets of the era, possibly including Wilde but also Swinburne and Rossetti. (The verdict seems to be out on this one.) This amounts to a far richer harvest than I ever dreamed of when I first started writing about three newly recorded Wilde-inspired works.

But Castelnuovo-Tedesco took on the biggest challenge, perhaps, by setting one of the drawing-room comedies, nearly entire—and making it work as an opera. (It seems that nobody has tried this before, for example with A Woman of No Importance or A Perfect Husband.) Quite an achievement—for the composer and for Odyssey Opera!

Late bulletin: I just learned that another composer, Gerald Barry, made Importance into an opera (first concert and staged performances 2011 and 2013, respectively). He condensed the text drastically, so the whole thing is half the length of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s. Lady Bracknell is sung by a bass, sometimes in falsetto. The style is apparently much more modernistic than that of the Castelnuovo-Tedesco, but intensely theatrical. A recording is available.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. He contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Odyssey Opera, Oscar Wilde, Ralph P. Locke