Opera Album Review: The Operatic Artistry of Leonardo (Not “da”) Vinci

By Ralph P Locke

A world-premiere recording of Siroe, King of Persia makes it clear that Leonardo Vinci (1690-1730) was as fine a craftsman as the painter with a similar name.

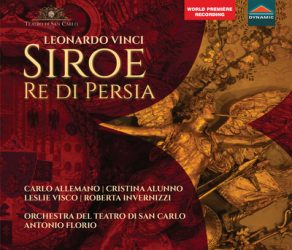

Leonardo Vinci, Siroe re di Persia

Roberta Invernizzi (Emira/Idraspe), Daniela Salvo (Laodice), Leslie Visco (Medarse), Cristina Alunno (Siro), Luca Cervoni (Arasse), Carlo Allemano (Cosroe)

San Carlo Theater Orchestra, conducted by Antonio Florio

Dynamic [3 CDs] 159 minutes

Click here to buy

Composer Leonardo Vinci. Photo: Wiki Common.

We live in an age of operatic riches. True, not always at the biggest opera houses, which can at times be burdened by the demand to program certain familiar operas again and again, with singers who are well known and may be a bit past their vocal prime. As a result, fresh and relevant opera can, at least as often, be encountered at performances by opera companies with lesser budgets (e.g., Glimmerglass, Santa Fe, St. Louis), by organizations presenting unstaged or minimally staged performances (Boston’s Odyssey Opera, Washington Concert Opera), and by outfits devoted specifically to operas of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Opera Lafayette, Boston Early Music Festival). And then there are recordings and videos, bringing us works that even those smaller and mid-sized companies haven’t yet touched.

Here is one such work by a composer whose works are rarely if ever presented in North America: Siroe, King of Persia, by Leonardo Vinci (1690-1730), a short-lived but highly accomplished composer unrelated to the famous artist with a similar name.

Many opera lovers know a different Siroe, namely Handel’s, at least three recordings of which have been released since 1985. Metastasio’s libretto was set (directly, or in some adaptation) by some three dozen composers, including Hasse and Vivaldi. Here we have the libretto’s very first setting, by Vinci. Until recently I knew very little about Vinci (except that he wrote some influential comic operas in Neapolitan dialect). So I am playing catch-up here: there have been at least seven other releases of Vinci operas, cantatas, or aria collections over the past thirty years. My own initiation was with a recent recording of his Didone abbandonata (1726), which came from the Maggio Musicale festival (Florence) and which I praised highly in the January/February 2018 issue of American Record Guide.

This first-ever recording of Vinci’s Siroe arrvies from the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, which has for centuries been one of the world’s major opera houses. The orchestra is not, as I at first feared, oversized. Quite the contrary, it consists of a mere seventeen string players, pairs of oboes and horns, and a four-person continuo group.

The work was recorded in November 2018, over two days that included a concert performance — i.e., unstaged, with no sets or costumes. (The booklet contains vivid photos of the singers gesturing and in mid-cry.) The performing materials were prepared by the conductor Antonio Florio. The manuscripts apparently contain no setting for an aria text that Metastasio had given to the minor character Arasse in the middle of Act 2. As a result, Cosroe, a bit oddly, gets two arias in a row. But the arias are separated by seven minutes of recitative interchanges among various characters, first without Cosroe (who of course left after the first aria), then including him (after he re-enters and before he leaves again).

Much as in Didone, Vinci keeps the musical means modest. The numbers (after the overture) are all solo arias — no duets, choruses, or dance numbers — and there are only three accompagnato recitatives and three arias with wind instruments. Vinci sometimes uses his small orchestra in strikingly imaginative fashion: in the overture and the three accompagnati but also in the arias. For example, King Cosroe’s aforementioned first aria in Act 2 (CD 2, track 8) echoes, through unsettled, halting string figurations, his bewilderment about whether to punish his son Siroe.

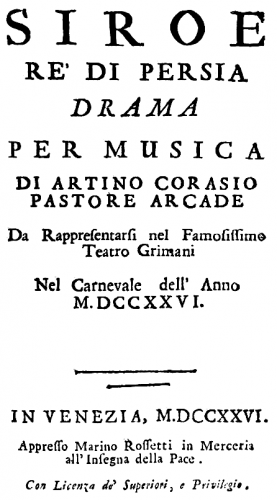

Title page, Siroe re di Persia.

The contorted plot involves a king of ancient Persia (Cosroe, i.e., the great Sasanian conqueror known to history as Khosrow II Parviz); his two sons (the younger of whom, Medarse, is envious of the elder, Siroe, who is headed toward succeeding their father as king; these, too, are figures from history); a captive princess (Emira), whose father Cosroe has slain and who, seeking revenge, has disguised herself (to everyone but Siroe) as a young man; the Persian general (Arasse); and the latter’s sister (Laodice), who longs for Siroe but is desired by Siroe’s father, the Persian king. A further complication: Siroe does not return Laodice’s affections, since he is drawn to Emira.

There are false accusations of abusive sexual advances such as might easily make headlines today. And Siroe, at one point, begs Emira (in vain) to kill him. But everything gets straightened out in the final scene, as was typical in the genre of opera seria. The knots in the plot are sliced largely by Cosroe, through acts of forbearance and forgiveness that make him a model of what was called at the time a “clement” (i.e., benevolent and self-denying) prince.

The arias are shapely and respond well to the character’s hurtling emotional shifts. Early in Act 3, Laodice, in an aria with two (specified) “hunting horns,” castigates the king for wanting to kill Siroe: a tigress would “fiercely” and (an even more pointed word) “humanely” defend her cub from a hunter. Soon thereafter, Cosroe sings a touching aria after learning that Siroe (whose death he has commanded and whom he therefore now believes dead) was actually innocent.

The performance is quite involving. (It can be streamed at Naxos, Spotify, YouTube, and other online sites.) Tempos are well gauged and contrasted, yet they never rush frantically nor slow to a crawl. As so often in recent years, the singers have been coached well, bringing a gaggle of contrasting characters to life before our ears while also embellishing the arias stylishly. You have to pay attention to the libretto because, of course, Emira is in disguise as a man (most of the time) and both of the Persian princes, Siroe and Medarse, are castrato roles here sung by women. (No countertenors in this recording.) It probably helps, especially in the recitatives, that the singers are mostly (or maybe all) native Italian-speakers.

I particularly enjoyed the effortless and spontaneous-sounding singing of soprano Leslie Visco (about whom I find little information, even online) as the younger brother Medarse. Mezzos Cristina Alunno and Daniela Salvo do wonders with the roles of the elder brother Siroe and Laodice (who loves Siroe hopelessly). Soprano Roberta Invernizzi, as Emira/Idraspe, displays a vast expressive range without ever losing the core of her sound, except in a few vivid moments of spitfire vengefulness. I see that she was 52 years old when the recording was made. Well, that goes to show how healthy a voice can remain if one sticks with roles that are within one’s powers!

The beefy tenor Carlo Allemano performs solidly as the king, especially in softer passages. His coloratura is huffy. The light tenor Luca Cervoni seems far too young and green as the Persian general Arasse, whereas in an operetta his basically sweet sound might be endearing.

The voices are recorded up close, but the orchestra is nicely audible as well. At one point, Invernezzi turns the page of her score with what sounds like character-appropriate fury.

The libretto and the extraordinarily detailed essay by the prominent musicologist Dinko Fabris are given in Italian and English. The translation of the essay, though, is often hard to understand, or inadvertently humorous. One sentence (about the hunting-horns aria) is fourteen lines long and, at least in English, quite tangled. In another sentence, “authors” means composers. And we read of the tenor Paita, the first Cosroe, that his “distinguished career . . . would conclude in the lagoon.” The intended meaning is that he died in Venice, presumably on dry land rather than by drowning. Earlier there is an oblique reference to “the lagoon city” (unnamed up to that point, though we eventually figure it out).

More seriously, we are not told how much has been omitted from the score. An aria for Medarse (with trumpet obbligato) is mentioned several times in Fabris’s essay but is not included in the recording. Indeed, the entire Act 3 Scene 8 is missing, the only clues being that the libretto jumps from Scene 7 to Scene 9 and that the libretto, as printed in the booklet, fails to point out that Medarse exits before Scene 9. Similarly, we are not told that Arasse exits before Act 2 Scene 9. I suspect that Vinci’s recitatives have been abridged significantly, though it is possible that he simply didn’t set all the verses found in the libretto at the University of Padua’s marvelous online Progetto Metastasio site.

Still, this is a first-rate rendering of a highly accomplished and thought-provoking work. I continue to be astounded at the craftsmanship in many eighteenth-century operas that have gone forgotten until recently, and at the artistry of the singers and other musicians who devote themselves to bringing these significant pieces to our attention. And, for all of us haters of unmusical noise, I am pleased to note that the recording preserves no applause except at the end of each act. This welcome emphasis on Vinci’s music makes me eager to listen to the thing all over again, as I shall now do.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Antonio Florio, Dynamic, King of Persia, Leonardo Vinci, San Carlo Theater Orchestra