Theater Review: “King John” — Fractured History Lesson

By Bill Marx

Praxis Stage picked the right time to stage a Shakespeare play about a head of state who doesn’t have anything on his mind but corruption.

King John by William Shakespeare. Directed by Kimberly Gaughan. Staged by Praxis Stage at the South End / Calderwood Pavilion at the BCA, Boston, MA, through February 16.

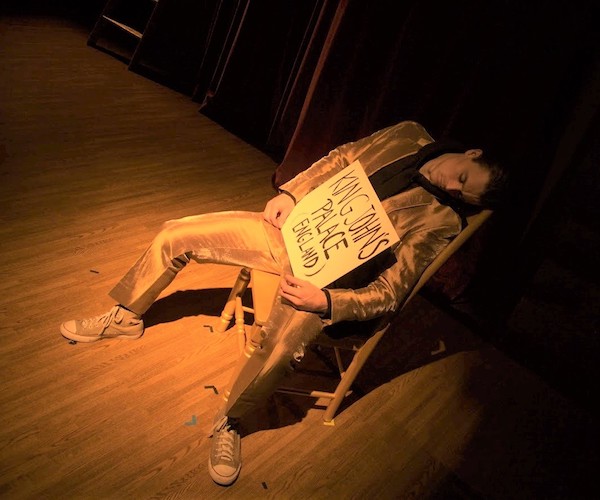

Michael Underhill as King John in the Praxis Stage production of King John. Photo: Rory Lambert-Wright.

It was no doubt serendipity but, with America slowly turning into a monarchy under an inept ruler, Praxis Stage chose the perfect Shakespearean history for our worrying predicament: the notoriously difficult to stage King John, which takes place in time well before the Henriad, and deals with a manipulative, weak, treacherous, and lying monarch. The feckless John shifts with the political winds, first suggesting someone be murdered and then denying he did so, defying the Pope and then giving in, using pomp (there are three coronations—no mention of crowd size) to feel better about himself and to reinforce his shaky hold on power. Perhaps it is because of John’s narcissism that Shakespeare leaves out the king’s reluctant effort at power-sharing — signing the Magna Carta. The Bard also ignores Robin Hood, the era’s version of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

John also believes he may be a usurper, if only because others do. Arthur, the son of John’s brother Geoffrey, is a legitimate rival claimant for the throne, though historians agree that John’s claim is as strong as Arthur’s. In fact, it might be stronger, given that Richard I named John as his heir. (In medieval times, primogeniture was not the sole justification for succession. Being chosen by the previous, dying king would have been equally important.) The script is the equivalent of a jump ball between two lousy choices: a conniving mediocrity versus a child the Bard depicts as feeble and helpless but who is backed by France’s King Philip and the Papacy. The war between bad alternatives without a saving way out turns King John into a one-off history lesson: an exercise in realpolitik without any morality play underpinnings. We are given a spectacle of treachery on all sides, a vision of double-dealing (pretty much at the mercy of the wheel of fortune) that includes not only King John and his foes, but his enablers as well.

Why did Shakespeare write the play? Elizabethan audiences would have cheered the antipapal action. It also offered a peek at the deceitful goings-on among the royals (at a polite historical distance), along with giving the Bard an opportunity to exercise the muscles of his developing genius. The Bastard, Philip Faulconbridge, supposedly the illegitimate son of Richard Coeur de Lion, the previous king, represents an enormous theatrical step forward. The Bastard is John’s loyal follower, but he is not your standard ambitious henchman. His independent, moral/amoral personality, a charismatic blend of the comic and the heroic, anticipates such males to come as Mercutio, Falstaff, Touchstone, and Henry V. Linguistically, the plainspoken Bastard, as he takes us into his confidence, blasts the other characters off the stage: “Zounds! I was never so bethumped with words/ Since I first called my brother’s father dead.” Constance’s magnificent lament for the death of her son Arthur has been admired, but I am partial to Richard’s semi-delirious speech as he is dying: “There is so hot a summer in my bosom/ That all my bowels crumble up to dust./ I am a scribbled form drawn with a pen/ Upon a parchment, and against this fire/ Do I shrink up.” His predatory calculation drops for a moment and we glimpse, amazingly, consciousness in free fall—as we do far more powerfully in the second half of another of Shakespeare’s plays of the period—Richard II.

The cast of Praxis Stage’s King John. Photo: Dawn Greene.

As for Praxis Stage’s production, it worried me at first that Trump was far from the mind of director Kimberly Gaughan. She writes in the program notes that beneath the characters’ “ambition surges the everlasting desire to be seen and to—somehow, against all odds—connect.” Thankfully, this King John offers no Kumbaya moments. Gaughan’s approach is playful and tongue-in-cheek, spiced up with musical interludes (a punk version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” etc) that put an amusingly ironic spin on the proceedings. The catch-as-catch-can costumes (such as John’s gold suit and sneakers), props (crowns that are lowered from the ceiling), and the doubling and tripling of roles give the staging some absurdist pizzazz, a wry sense of the ridiculous that fits at times: such as when the feuding sides decide they would rather decimate a French town than work out their differences, or King John’s poisoning by a monk while his forces (via luck and French self-sabotage) manage to turn things around and triumph. This is one way of handling the play’s lumpy weirdness. I thought of Kurt Vonnegut’s “So it goes.” Nietzsche said that “power makes stupid,” and the notion that history is pushed dumbly along accounts for the play’s lack of sympathetic characters, sudden switches from comedy to tragedy, and the humbling suggestion that accident controls a country’s fate.

The catch is that Shakespeare’s dissection of realpolitik is built on something real. There is nothing at stake in this absurdist romp: the death of Arthur as well as the (unsatisfactorily) stylized battle scenes make little to no emotional impression. By turning King John into a cartoon — sometimes it feels as if we are watching squabbling suburban neighbors getting ready for combat on The People’s Court—Praxis Stage settles for a watchable, but at times sloppy, even amateurish, product.

The evening’s broad performances, including the cast’s slack delivery of the verse, reflects the lack of discipline. Annalise Cain delivers all of the magnificent Bastard’s speeches with a stern earnestness, Michael Underhill’s King John sports an effectively feral look, but he throws away the monarch’s best lines. David Picariello simply hasn’t the range to play three pivotal roles—they all glom together into the essence of nebbish. Daniel Boudreau takes on four characters, including the Duke of Austria and Pandolf, the papal emissary. He leans into the staging’s comic spirit: the dead crow fright wig he dons as Austria should be recognized with a separate credit on the program. Jeremy Johnson brings sturdy dignity to King Philip and the would-be assassin, Hubert. Poornima Kirby strives to do right by Constance’s mourning, while Mary Potts Dennis as Queen Eleanor and Jane Regan as Lady Blanche provide pedestrian support.

Still, for all of the faults in its production, Praxis Stage should be congratulated. The company picked the right time to stage a Shakespeare play about a head of state who doesn’t have anything on his mind but corruption. The play’s cynical truth is useful now because it hurts: John’s ouster is simply a matter of chance.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England