Classical Album Review: Poisonous Delicacy — Kurt Weill’s “Seven Deadly Sins” and the Wit of Dorothy Parker

By Ralph P Locke

I had never heard of Marcus Paus before, but his work I Hate Men, set to witty verses by Dorothy Parker, proved to be one of the most entertaining and engaging pieces I have heard in recent years.

In 2008, mezzo-soprano Tore Augestad (b. 1979) won the Lys Symonette Award at the Lotte Lenya Singing Competition (held annually at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music). I remember being impressed by her vocal skill and her sense of style but not by any special individuality or vividness. Maybe the judges thought so as well, because the Lys Symonette Award is often given to a contestant who shows remarkable abilities but doesn’t quite pull everything together in the special “singing/acting” way that the Competition is designed to recognize and honor.

Over the past dozen or so years, Augestad has had quite a career, as one can see on her website. Since graduating from the Norwegian Academy of Music, she has performed in a wide range of works and contexts, from Handel opera to newly commissioned works by the renowned German composer Beat Furrer.

She has also promoted the works of Weill, notably in a CD entitled Weill Variations, which came out several months before I heard her in Rochester. (See some review excerpts here.)

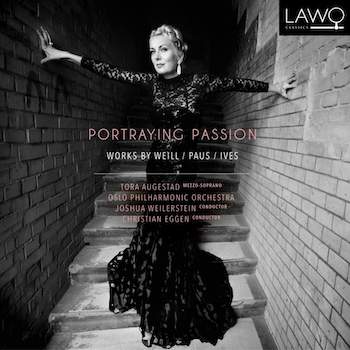

Augestad’s latest CD (see trailer here) offers four works, beginning with that poisonous delicacy by Weill (to a text by Brecht), Die sieben Todsünden (The Seven Deadly Sins). Many of us grew up on recordings of the work made by Lotte Lenya or (my own special preference) Gisela May. In recent decades, the work has become a specialty for “legit” sopranos or mezzo-sopranos with special dramatic flair (e.g., Angelina Réaux or Anne Sofie von Otter). They tend to sing the work in its original keys, not the downward transposition made for Lenya’s use in her later decades.

Augestad falls somewhere between the two camps, being a conservatory-trained singer who has made a specialty of cabaret performances. (Indeed, her degree at the Norwegian Academy of Music in Oslo was in cabaret singing. I wonder how many other music schools have this major, which seems to me rather specialized.) The result should be ideal, but I found it a little wearisome. One problem, for my taste, is Augestad’s upper register, which is often “white” (i.e., stripped of vibrato) and cuts like a knife, or else flutters very quickly (like, actually, recordings that Lenya made when she was young—i.e., when she spelled her name Lenja!). Another is—sorry to have to say this—her lower register, which is weak and becomes very breathy when she applies any pressure to it. I wondered at times if Augestad can really perform Todsünden without a microphone, in front of a full orchestra. If her vocal weaknesses were counterbalanced by greater variety in delivery of the text, I would have felt more drawn in. But there seems to be a blanket of reserve stretched over her reading of the work. (Here is Augestad singing the final “sin”: Envy.)

The Oslo Philharmonic is conducted alertly by Joshua Weilerstein, but it sometimes sounds recessed, perhaps in order to allow Augestad to be heard clearly. The male quartet is not always up to snuff. Their tone is often rough and unsteady, making it hard for me to hear Weill’s keenly chosen chords in the extensive a cappella passages. The work’s long tenor solo (in the “Gluttony” movement) is a trial.

I feared that I was rejecting a new reading of an important work because it differs from the ones I’m most familiar with. So, for a fresh comparison, I started looking around and found a recording that I didn’t even know existed: by the renowned mezzo-soprano Brigitte Fassbänder, with the Radio-Philharmonie Hannover des Norddeutschen Rundfunks conducted by Cord Garben (1992, now available on Harmonia Mundi). Night and day! Here is a well-regulated voice, from top to bottom, with endless colors galore, and a native German-speaker’s nuanced command of quasi-spoken inflection (without ever breaking the flow of tone that keeps the voice projecting over the orchestra). In short, I found much more of the cabaret-artist’s art here than in Augestad’s thin-voiced and relatively undifferentiated reading.

Augestad, though, can do marvelous things. This is shown by I Hate Men, a three-movement song cycle composed for her by the Norwegian composer Marcus Paus (who, like Augestad, was born in 1979). I had never heard of Paus before, but this work, set to witty verses by Dorothy Parker (1893-1967), proved to be one of the most entertaining and engaging pieces I have heard in recent years. I Hate Men uses a chamber orchestra and includes many prominent passages for one or several woodwinds.

Singer Tore Augestad — she can do marvelous things.

Throughout the Paus work, Augestad makes keen and varied uses of her various registers, sometimes sounding a bit like Barbara Streisand in her upper register and pushing hard into her inadequate low tones in order to produce a comical effect (as when repeatedly insisting — protesting too much? — that she absolutely hates men). Alas, her pronunciation of English is uneven. Sometimes it is vividly clear, other times confusing. For example, she does not always vocalize a final d, and thereby turns it into a rather emphatic t. “Intended” becomes “intendetttt.”

The CD continues with Augestad’s performance of the five songs by Charles Ives in the orchestrated version that John Adams made for Dawn Upshaw. Here, Augestad tries to bring a vernacular flair to the task, but she often seems not to be making contact with the songs’ emphasis on familial and community warmth or on philosophical idealism. Her reading of the prose text that begins “Thoreau” is extremely well pronounced (unlike her singing) but lacking in nuance and variety — I listened to renderings by Susan Graham and by Robert Gardner (of the original piano-accompanied song) to find what was missing here. And Augestad sounds simply puzzled by the oddities of “At the River.” The 1989 Dawn Upshaw recording (with Adams conducting) remains a touchstone of vocal and interpretive artistry.

The recording concludes, imaginatively, with The Unanswered Question, as if growing out of the last of the Ives songs (“Serenity”). The trumpet part is as sensitively and securely played as I have ever heard it. The woodwind responses are more raucous than I ever recall hearing them, which I assume was a conscious choice by conductor Weilerstein. I don’t think I much want to hear it played this way again, but it certainly “stages” the composer’s program effectively.

In short, an intriguing attempt at something unusual and different. And a delightful introduction, for many of us (I imagine), to an imaginative youngish composer: Marcus Paus. I look forward to hearing more from him, and more from Augestad (especially if she keeps working on her English, or sings in her native Norwegian).

The booklet gives the Kallman/Auden singing translation of Brecht’s text, which is often quite free. The booklet essay is often a bit unidiomatic in English, and sometimes a bit misleading. The worst error is the suggestion that one of the Ives songs evokes Stephen Foster. In fact, it quotes, at length, one of the best-known English hymns, “Nearer, my God, to Thee.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). A shorter version of this review first appeared in the Kurt Weill Newsletter and is here re-used with kind permission.

Tagged: I Hate Men, Joshua Weilerstein, Marcus Paus, Oslo Philharmonic, Ralph P. Locke, The Seven Deadly Sins