Music Commentary: Ken Burns’ “Country Music” — Superb Cinematic Storytelling

By Daniel Gewertz

Country Music digs into the rich, deep dirt of a music with a complicated past, a hybrid genre soaked in soulful suffering, twangy glory, and times both high and tough.

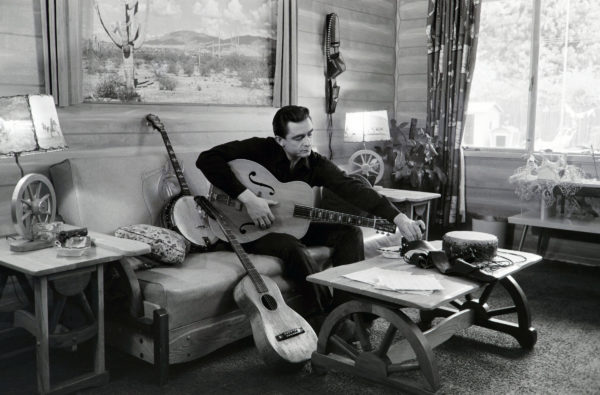

A scene from Ken Burns’s PBS series “Country Music.”

Jazz bebop legend Charlie Parker had a habit, while in diners, of putting nickels in the jukebox and selecting country & western hits. This was in the late 1940s, the honky-tonk era of Ernest Tubb, Eddy Arnold, and Hank Williams. Bird’s bandmates would look at him as if he were a lunatic, and ask why. Why hillbilly?

“Because of the stories,” he’d say.

That’s the same answer filmmaker Ken Burns gives when asked why he’s made a mammoth 8-episode, 16-hour series on the genre of country. Some critics have carped that Country Music devotes too much footage to juicy tales as opposed to an academic exploration of the music’s development. The documentary has a few flaws, but a surfeit of superb storytelling isn’t one of them. You should not ignore the wild and wonderful in a genre haunted by drink, drugs, feuds, catastrophic deaths, and public betrayals. The Grand Ole Opry alone was studded with a circus sideshow of freaky theatrics: stars like the 4′ 10″ Little Jimmie Dickens; a clownish banjo player named Stringbean; Brenda Lee, a tiny child singer with the raspy voice of a worldly-wise woman; and Bob Wills, a brilliant genre-bending fiddler who squealed and pranced onstage like a combination of Mick Jagger, Dame Edna, and an excited rooster.

The series, which presents the first of its final four episodes tonight at 8 p.m. on PBS (locally, WGBH-TV), digs into the rich, deep dirt of a music with a complicated past, a hybrid genre soaked in soulful suffering, twangy glory, and times both high and tough. With over 3,000 photos, 600 music clips, 100 interviews, and 8 years in the making, Country Music manages to tell scores of cogent tales while mentioning hundreds of musicians. Yet still, a review in Pitchfork bitterly complains that some are left out. In one absurd example, the writer takes Burns to task for calling Willie Nelson the figurehead of Austin’s “redneck-hippie” scene without mentioning the organizational role of musician Doug Sahm.

The series seems an odd project for Burns, in the sense that the elegant Burns-style slow-mo panning of ancient photos, and narrator Peter Coyote’s patient, august voice, might seem in theory a mismatch for the hyper-commercialized subject. But Burns knows that once cultural cheese becomes hoary with age, it grows just as intriguing as past wars or politics. Burns’s job has always been to construct human monuments, and he’s chosen well here. Honest, knowing insiders Marty Stuart, Rosanne Cash, Bill Anderson, Ketch Secor, Brenda Lee, Ray Benson, and the late Merle Haggard are respectful, but cut through the usual bombast. As Stuart says, country music tells the truth “even when the truth is a big fat lie.” The possibility of hokum hovers over this project, but never ruins it.

I admit that I have loved some mid-20th-century country stars since I was a teenager in late 1960s Queens, NY, listening to a mail-order discount LP called Greatest C & W Hits. Briefly, in 1981, I was an overnight deejay on WDLW-AM, Boston Country. But my affections ended long before the century did. When I heard the trailer for the series, and songwriter Harlan Howard’s famed line “Country is three chords and the truth,” I yelled back to the TV: “More like three chords and a cliché!” While once keening country songs ennobled the struggling, now it’s more about the dumb brags of the comfortable. And the peculiar has plumb left the stage. So, when I found out that the whole series ended in 1994, and what’s more, that the last episode would be dominated by Johnny Cash’s haunting return to stripped-down, mournful song, I was immeasurably cheered. This series wouldn’t have to make believe that country was still cool, despite it’s monstrous dominance in the entertainment industry.

With that one savvy move, Country Music will likely avoid most of the insults that Burns’s 2001 Jazz series suffered. In many ways, jazz and country have had opposite journeys. From 1925 to 1970, the new jazz stars were adventurous pioneers staking out modern visions. The “rebels” of country, meanwhile, looked backward, attempting to reclaim a lost purity. The yearning to reclaim the past was built into the music from day one. The passing of jazz music’s most popular incarnation – white 1940s swing — was not mourned by the genre’s truest fans. As jazz dropped from the charts, there were decades of legendary, forward-thinking music to come.

Johnny Cash at his home in California, 1960. Credit: Sony Music Archives

Country, as Burns and writer Dayton Duncan ably relate, flourished as a radio attraction, with numerous broadcast stage shows, Chicago’s National Barn Dance, the Louisiana Hayride and Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry chief among them. The postwar golden age – presaged by the success of Jimmie Rodgers – was sparked by “The Hillbilly Shakespeare,” Hank Williams, along with Ernest Tubb, Lefty Frizzell, Eddy Arnold, Bill Monroe, and so many other honky-tonkers, bluegrassers and balladeers. It was an era of simultaneous artistic excellence and commercial success.

So, if Burns and Duncan brought their massive series up to the present date they’d either have to lie about the quality of today’s superstars or come off as effete northern intellectuals. Either way, they’d make enemies. Remember the ruckus that Jazz provoked in 2001? Because the series shoehorned everything post-1970 into a scant few minutes, as an afterthought, an onslaught of near-invective was unleashed by current jazz musicians – many of them barely making a living – who claimed that jazz was as great as ever, and the golden age never died. It was the very definition of a tempest in a teacup.

Who is this series made for? Present-day country fans, always on the lookout for insult from smart-ass northerners, will appreciate the literate serious treatment. The musically savvy will already know many of the stories. Ultimately, the series wants to appeal to Burns fans, who might have some small affection for country music, and would be gratified to discover that hillbilly music (as it once was officially called) wasn’t as tacky, backward, and racist as they might have feared.

The project’s weakness is rooted in Burns’s deepest instincts. He has always wanted his massive works to uncover hard truths, but to ultimately accomplish nothing less than to heal this ragged torn nation. So, Burns and writer Duncan emphasize, over and over, the black influence on Country, the genre Kris Kristofferson admits is largely the art of the white working class. Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, Bill Monroe, and Johnny Cash all, as kids, were taught at the feet of black musicians. As Stuart says, the music would have been far different if they hadn’t. One African American, harmonica wizard DeFord Bailey, was a regular on the Grand Ole Opry, until he was fired. Decades later, another African American, Charley Pride, became a bona fide star. He was the only one. While it is admirable for Burns to make race a prime point, it is debatable whether the point is made to give nonwhites their due, or to make Americans feel better about an openly racist past. One of the frequent interviewees, Rhiannon Giddens, the brilliant singer/banjoist (formerly of the black string band Carolina Chocolate Drops) calls the widespread artistic borrowing between races a “beautiful boiling pot.” Others may see it as cultural appropriation. But one thing is indisputable: it was not a fair trade. The whites gained fame and money while their inspirational African American tutors remained obscure and poor.

I am looking forward to the final four episodes. While it may not heal the nation’s wounds, Country Music is superb cinematic storytelling. Like a great country song, emotion is at its heart. See if you can watch the eloquent footage devoted to the death of Patsy Cline without a tear or two.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the l970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Tagged: Country Music, Daniel Gewertz, Ken Burns

I’m so glad someone said this. I’m a Ken Burns fan, though I understand how sometimes he can miss the mark and/or be a sort of Cliffs Notes about important subjects (The Civil War, Vietnam, etc.) and be overly traditionalist about others, like Jazz.

But for my money there’s no one better positioned to popularize a subject like this, which often gets dismissed or condescended to. Lots of people will now be exposed to people who are no doubt well-known in the country world but aren’t necessarily household names, like Johnny Cash and Hank Williams. I bet there are a lot of people out there who will be more interested in the likes of Roy Acuff, Chet Atkins, Lefty Frizzell and others who wouldn’t have heard much from them otherwise. And that’s a good thing.

Although at the same time giving about five minutes of attention to The Louvin Brothers is all kinds of wrong.

Thanks for your comment, Matt. I somehow didn’t see it until these months later. Lefty Frizzell is just the sort of talent that gets lost in the cultural shuffle… despite the lengthy life of of “Long Black Veil.”