Book Review: “As a River” — How Secrets Divide

By Katharine Coldiron

As a River is a sensuously and smoothly written book, a heartfelt meditation on what divides us from each other and from love.

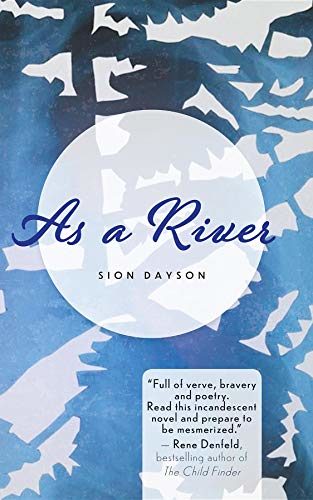

As a River by Sion Dayson. Jaded Ibis Press. Paperback, 218 pp. $17.99.

At the heart of Sion Dayson’s debut novel is secrecy. The atmosphere, the place and time, the characterization, the clear prose, all heighten the tension and textures rooted in the hidden. At some point, secrecy harms every character in the narrative. Some of these injuries prove impossible to mend, while others only heal with time — the kind of time that slowly reshapes stones at the bottom of a river.

In Bannen, Georgia, 30 years don’t change much about daily life, despite those years seeing the passage of Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement. In 1977, when As a River opens, the town remains divided between black and white: each group sees the other as alien and dangerous. The novel uses multiple third-person narrators to hop around in time: back to the 1940s, and then forward to 1977, and then back to 1961. Each moment illuminates another aspect of Dayson’s sorrowing characters as well as life in the 20th-century South.

Greer Michaels, born in 1945 to a black mother and a white father, sits at the crossroads of race and place, his itchy feet causing him even more pain than the mystery of his identity. In 1961, the tale of Greer’s ill-starred teenage love affair with a white girl, Caroline, unfolds slowly and achingly. Sixteen years later, the now well-traveled Greer returns to Bannen to settle debts with his sick mother. Across the street lives Ceiley, an enthusiastic and impatient teenager who wants to leave Bannen behind, as Greer has, but who doesn’t understand that home won’t necessarily stay where it belongs. As he explains to her, “You leave this town because you’re angry, leave with unsettled business — believe me, you’ll never really escape it.”

At first, a separate strand of the plot seems to concentrate on Ceiley, but her role becomes that of a passive observer as Greer’s story takes center stage. The major secret of his mother’s life (his father’s identity) entwines with a major secret of his own (his love for Caroline), until one suppression destroys the other. Perhaps the revelation of this twist is a little predictable, but the book is no less satisfying for being overly coincidental.

And As a River is such a pleasure to read. Dayson writes with gentleness and affection for her characters and their struggles. She buttresses the story with effective metaphors, as when Greer must replace some of the plumbing in his mother’s aging house:

Such a simple task: replacing the old parts with new, taking everything apart and putting it back together. Greer had not come back for this, but he realized just the same: he’d have to disassemble everything if he were to move forward. What he would put back in its place, though, he really couldn’t say.

Author Sion Dayson. Photo: Facebook

Similarly, the river near Bannen is a source of both life and death for its residents. One girl goes there for fun and leaves a widow; another arrives there to kill herself and leaves in love. Returning to Bannen, Greer visits that river — but no longer the same river, at least for him. Ceiley runs to the river without understanding its meaning for those who live around it. For them, the river is time and life and family — all wrapped in one body of water. Dayson explores these archetypal resonances with skill.

While the central conflict of As a River wouldn’t exist without the miserable history of racism in the South, racial tension provides less a background than a means of psychological pressure in the narrative. Dayson never pushes on race too hard — just hard enough. Greer is always aware that he could easily be killed for loving Caroline. When he goes to see a white family on “the other side,” a white neighborhood, he must use the back entrance to their house. Greer’s mother, Elizabeth, is black and a maid and his father is white and her employer. Over time, Elizabeth concedes to and then even encourages the white man’s sexual desire as a way to blot out her own grief and trauma. What happens between these two people — their taboo, not-quite-consensual coupling — is chaotic and ugly. “A place doesn’t have to be big for meanness to set itself down on you,” Elizabeth observes. Or, in Greer’s narration: “The women in this town…Had every single one of them been hurt? Was there anyone walking around without wounds?”

All the characters in As a River desperately need love and connection, especially as an antidote for the poison of secrecy. Dayson presents the passion between Greer and Caroline as a rich drama, filled with possibility, and narrates the crush Ceiley develops on Greer with almost embarrassing precision and sensitivity. This is a sensuously and smoothly written book, a heartfelt meditation on what divides us from each other and from love.

Katharine Coldiron‘s work has appeared in Ms., the Guardian, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in California and blogs at the Fictator.

Marilyn Agney

October 5 at 6:04 PM ·

Sion is from Chapel Hill. “As a River” is her debut novel. I just “devoured” the book … couldn’t put it down. Check it out.