Book Review: “William Walker’s Wars” — Revisiting US Slavery’s Soldier of Fortune in Latin America

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

A new biography of the oft-forgotten ‘filibuster’ provides ample facts and little thesis. Is that enough — don’t we need more?

William Walker’s Wars: How One Man’s Private American Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras by Scott Martelle. Chicago Review Press, 288 pages, $26.99.

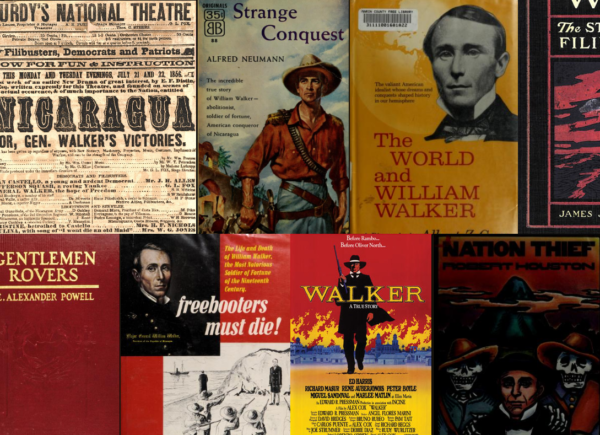

Walker through the years: an 1856 theatrical production in New York; Walker as an “abolitionist” on a 1954 cover; “The valiant American idealist whose dreams and conquests shaped history in our hemisphere” in 1963; a “gentleman rover” in 1913; protagonist in a 1987 film with music by Joe Strummer.

In the autumn of 1855, amid a civil war between that country’s Liberals and Conservatives, two white men walked along the Pacific coast of Nicaragua. Both had arrived from the United States that summer to claim Nicaraguan citizenship. One was a Nashvillian named William Walker, leader of a contingent of men who arrived with him from California at the invitation of the Nicaraguan liberals. Now armed, they prepared for an attack on the conservative stronghold of Granada. On those sands, as his beach companion would later recount, Walker elaborated a grand vision: to “wield the temporal power over Central America and Mexico […] under the domination of Southern ideas.” Slavery, having been abolished in Nicaragua for decades, would make a comeback under Anglo-American stewardship. And Walker, who would soon take control over the country and eventually declare himself its president, was not on his own in this endeavor.

Walker had the backing of investors from the South, but also from New York and San Francisco. He had an army of predominantly Northern men, but also Europeans. He also had the support of Cornelius Garrison (New Yorker, fifth mayor of San Francisco) and Charles Morgan (from Connecticut), a magnate responsible for developing transportation infrastructure in the South. With Walker, Morgan and Garrison conspired to usurp rival Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Nicaraguan investments and confiscate his assets. That would incense Vanderbilt, leading to Walker’s defeat by Vanderbilt-sponsored Costa Ricans. In the midst of it all, coming fresh from the infamous Bleeding Kansas conflict, a certain Colonel Titus brought his pro-slavery forces in to join the fight. When Walker addressed his mercenary-colonists in preparation for battle against the Vanderbilt’s Costa Ricans, he condemned their Central American hosts, alleging that white, Anglo-American immigrants were being racially persecuted. And oh, yeah, by the way… he had already tried such a private invasion in Mexico, and he would try it again three more times in Nicaragua, despite numerous efforts to stop him by multiple governments, culminating in his fatal decision to invade Honduras.

Walker is a figure who constantly reemerges in chronicles of American history, though he is usually dismissed as a figure on the margins, an obscure (if intrepid) adventurer. Of course he is not marginalized in Nicaragua, where poet Ernesto Cardenal wrote of him “taking dips in the ocean.” Nor was he forgotten in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936). Still, Walker, the tenacious “grey-eyed man of destiny” who via an unimposing demeanor ordered confiscations and death sentences, has remained a vague historical figure.

But during his time Walker took center stage. His relentless pursuit of ‘filibustering’ (in 19th century political terminology, the piratical usurpation and occupation of foreign territory) made him a hero and a scoundrel, an early sign of the great cognitive rift opening up in the antebellum US. His roots were in Nashville, in close social and geographic proximity to Presidents Jackson and Polk, famous territorial annexers. As a precursor to his own later filibustering, the course of events in Texas, in which Walker’s family and neighbors participated, no doubt impressed themselves deeply on the young Walker. Nashville itself, in fact, was part of the country’s acquisitive pattern, founded as it was against colonial law forbidding trans-Appalachian settlement.

Walker studied medicine in Europe. There he would have witnessed the fermenting of the “People’s Spring” of 1848 (not noted by biographer Scott Martelle), though he had finished medical school by the time the Revolutions had begun, briefly practicing in Philadelphia before heading to New Orleans to study and ultimately practice law. In New Orleans, Walker would also begin his third career — in journalism. In ’49 he followed the Gold Rush to San Francisco, where he continued to practice law and work in journalism. From San Francisco, he took in the filibusters of the day. Narciso López, who would invade Cuba in 1850 with the goal of overthrowing the Spanish government and making the island a Southern slave state (with Northern support). Then there was Joseph C. Morehead, who would use the ruse of allegedly transporting California miners to Sonora, Mexico to skirt the US Neutrality Act in 1851 (a tactic later used by Walker and others). There were French aristocrats Pindray and Raousset-Boulbon, recently fled from the revolutions of 1848 to San Francisco. In 1851 Pindray would strike a deal to settle in Sonora as a buffer against Apaches, but the endeavor collapsed. In 1852 Boulbon came and captured the capital of Sonora for a time. In 1853 it was Walker’s turn. After being denied permission to settle there, he returned to Sonora that same year with 45 men, captured it along with Baja California, and seceded from Mexico. The law of his Republic of Sonora reflected the slavery-sanctioning Louisiana Civil Code.

This, like his later Central American incursions, Walker did with financial backing as well as popular and political support from a wide segment of US society. Though he was crossing other segments, including the US government. The Feds made multiple attempts to stop Walker, either militarily or legally. But their efforts were thwarted, either by popular opinion or the tacit complicity of authorities. At that point, America was apparently in a schizophrenic state, split on the question of slavery. Walker’s career illuminates how seriously popular culture, media, military, government, and capitalist segments of society were divided, individuals sometimes acting contrary to their own stated positions or apparent best interests. This was the case when President Buchanan received Walker in Washington, after he had returned from his first filibuster expedition in Nicaragua. Surely he was aware that such a White House meeting implied an a least tacit acceptance of Walker’s plans. In fact, Buchanan, a Northern Democrat most remembered as the lame-duck that presided over the nation’s descent into sectional chaos, was at the time pursuing the purchase of Cuba … clearly, a real estate deal that would appease Southerners.

This, like his later Central American incursions, Walker did with financial backing as well as popular and political support from a wide segment of US society. Though he was crossing other segments, including the US government. The Feds made multiple attempts to stop Walker, either militarily or legally. But their efforts were thwarted, either by popular opinion or the tacit complicity of authorities. At that point, America was apparently in a schizophrenic state, split on the question of slavery. Walker’s career illuminates how seriously popular culture, media, military, government, and capitalist segments of society were divided, individuals sometimes acting contrary to their own stated positions or apparent best interests. This was the case when President Buchanan received Walker in Washington, after he had returned from his first filibuster expedition in Nicaragua. Surely he was aware that such a White House meeting implied an a least tacit acceptance of Walker’s plans. In fact, Buchanan, a Northern Democrat most remembered as the lame-duck that presided over the nation’s descent into sectional chaos, was at the time pursuing the purchase of Cuba … clearly, a real estate deal that would appease Southerners.

Powerful American capitalists were also in the mood to buy. In a response to competition from successful routes going through Panama, Vanderbilt turned instead to a route through Nicaragua. He proposed, and began plans for, a canal there, and in 1851 the Nicaraguans gave him an exclusive charter to transport passengers across the isthmus. Unbeknownst to Vanderbilt, who opposed the first Walker Nicaragua expedition of 1855, Walker had other plans. In a conspiracy hatched with Morgan and Garrison, who were in charge of Vanderbilt’s Nicaragua affairs, Walker confiscated Vanderbilt’s assets and handed them to his co-conspirators. Vanderbilt took immediate action, in the newspapers and legally. Then he turned to military action by way of Costa Rica. The Latin American proxy war fought over the antebellum rift had begun.

Walker periodically reemerges in US consciousness, and Martelle’s informative William Walker’s Wars is sparking just such a reemergence. His book is filled with illuminating facts and maintains the intrigue of the tale without falling into the trap of glamorizing or mythologizing. But does he take a strong position? There is an implicit thesis that differentiates this volume from an earlier work of similar scope: Filibusters and Financiers by William Scroggs (1916), whose on-the-fence attitude on Walker’s pro-slavery ambitions has not aged well. Still, Martelle’s description of Walker’s “presumptive white supremacy” falls short. The biographer cites that phrase as the catalyst for characterizing Walker’s pro-slavery sensibility in the historical record. But white supremacy was much more likely a motivator for Walker and his backers from the get-go, if only subconsciously. “Latent” would be a more accurate than “presumptive.” Latent white supremacy found an opportunity to erupt amid the buzz of democratic and republican political ideals in the mouths of Walker and his society. That white supremacy would erupt was inevitable. It was the social and economic precondition of the democratic American republic.

Walker began his life as a filibuster using the language of liberation. By the end of his career, he had sacrificed every ideal to his one objective: slavery. In the end, he even sacrificed faith and nation, opportunistically converting to Catholicism, and plotting the creation of a new slavery empire independent of the US South. Being familiar with the details of his life begs a vital question: is just knowing the facts enough? Is it enough to conclude that certain parts of his career illustrate a “presumptive white supremacy”? Or does the pathological nature of white supremacist ideology necessitate a more theoretical framework? Also, what remained of the antebellum order after the resolution of the schism? As for the capitalists, Vanderbilt became the wealthiest man in America, and Morgan would emerge wealthier after Appomattox, having maintained Confederate blockade runners. And, though he met his demise before a Honduran firing squad in 1857 — claiming to the very last that he was the President of Nicaragua — the spirit of Walker lives on.

Walker has a place in the historical record, but he is also part of our culture, via plays, novels, and films. It’s easy to see why such a life continues to captivate us. Walker gambled everything in that imaginary space of unhindered self-realization called the “Wild West.” That is not marginally American, it’s quintessentially American. Yet, on the other hand, he was enslaved to his profoundly racist (and surely classist) pathology. He accepted the rhetoric of Enlightenment Liberalism, but could not extend its application to others when it conflicted with his personal interests. Thus we have Walker, the contradiction… part of the great riddle of American history, the liberating ideals borne on the backs of the societally oppressed. This riddle is quintessentially American as well — much more so than racism. For it may be an existential question in the end, though our answers to it will shape our lives. To what extent are our ideals defined or curtailed by self-interest? Self-interest can color facts. Differing interests, differing facts — a cognitive rift. So facts cannot be enough… although they are the best place to start. We have the facts on Walker… now can we understand him?

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com, and he sometimes maintains a blog entitled That’s Not Southern Gothic.

Tagged: Chicago Review Press, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Scott Martelle, William Walker