Book Review: A Memorial to Lucette Lagnado’s Two Remarkable Memoirs

By Roberta Silman

To have such a remarkably courageous voice as Lucette Lagnado’s silenced forever at such a young age is, simply, not fair.

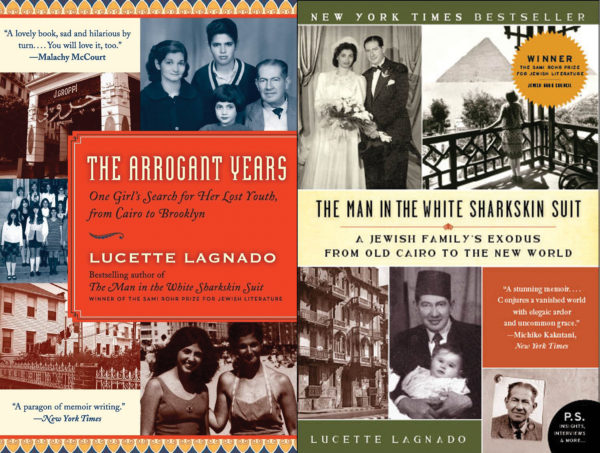

The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit (Ecco, 2007) and The Arrogant Years (HarperCollins, 2011) by Lucette Lagnado.

The late Lucette Lagnado. Photo: Facebook.

So far this summer we have had the deaths of two important writers: Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison at 88, who wrote the great books The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon (my favorite), and Beloved, as well as several far less memorable works, and that of Lucette Lagnado at the far too young age of 62, whose two memoirs The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit (which won the prestigious Sami Rohr Prize from the Jewish Book Council) and The Arrogant Years not only reveal the exotic world of Jewish Cairo in the 20th century, but also give us a totally relevant and sometimes heartbreaking portrait of how immigrants struggle in this wonderfully diverse but not always welcoming country.

In The Arrogant Years Lagnado describes visiting an old college friend who had just moved with her husband and young family to a new home in the Five Towns on Long Island, where, incidentally, my family moved when I was almost eight from Brooklyn. I left that suffocating enclave when I went to college in the early 1950s, never to return except to visit my parents, yet I could feel my heart sink when, after spending the day in the relative wealth and comfort of her friend’s home, Lucette wonders, “What did my family have to show for all our years in this country?”

I wish she were still alive, or that I had had the sense to read the second memoir earlier and write to her. The answer to her anguished question is: You. Lucette Lagnado, a highly intelligent girl who chafed early at the limits of Orthodox Jewry in Brooklyn yet had the passion and determination to know that she would carve a special place for herself in the world; a high school senior who endured treatments for Hodgkin’s disease and went on to graduate from Vassar; a courageous reporter who started her career at the Brooklyn Spectator, then worked for the muckraker Jack Anderson, who sent her to search for Dr. Josef Mengele in South America (she eventually co-wrote a book about his brutal experiments); a seasoned journalist who went to work for The New York Post and fell in love and made a happy marriage; a well-respected investigative journalist at The Wall Street Journal; a loving and talented daughter who took care of her often difficult parents and honored their memory with these two beautiful books.

That is surely success by any standard that I have ever heard of.

Lucette Lagnado was born in Cairo in September 1956, the fifth child of Leon and Edith, whose troubled marriage had almost come apart a few years earlier, and was nicknamed Loulou from the start. As Loulou matured she became the one destined to hold her parents and family together just because of the circumstances of her birth. There were Suzette, the rebellious oldest child; Isaac, the shadowy one; Cesar, the substitute patriarch as Leon grew old; and Alexandra, who died in infancy and whose death loomed over the family until Loulou was welcomed as the child of her father’s old age. She replaced the baby who died, and her temperament made her their most loving and lovable child. And she was the one destined to tell this family’s story — a story marked by personal disasters and triumphs, but that also embodies the broader narrative of the Levantine Jews of the 20th century whose details were rarely told because they were not part of that great catastrophe, the Holocaust, and because their innate pride and entrenched privilege precluded openness. But it is a story that is fascinating and important in its own right.

What makes these books so valuable is their mingling of historical fact and family reminiscence–facts that seemed very far away at the time but now seem excruciatingly close. Soon after Loulou’s birth Egypt went through its own revolution, and the benevolent and tolerant reigns—for Jews—of King Fouad and King Farouk ended. Farouk had abdicated in 1952, but things got worse when Nasser took over in 1956 and “Egypt was engulfed in a war with Israel, France, and Britain over the control of the Suez Canal.” Six years later Edith and Leon succumbed and left Cairo for Brooklyn, by way of Alexandria and Paris. They had held out as long as they could, but realized there was no future in Cairo, where Leon had been brought as a baby from Aleppo and where Edith had been born.

Jews were leaving in droves. . . . Countries where Jews had lived harmoniously with their Arab neighbors for generations found their situations untenable. One after the other, Jewish communities in Libya, Algeria, Yemen, Iraq, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, and, of course, Egypt dispersed. They left behind magnificent synagogues, schools, hospitals, and a way of life that had been, in many of these countries, blissfully free of intolerance. . . . The world, still reckoning with the aftermath of the Holocaust, was determined not to risk another slaughter of Jews. Country after country opened its doors, and from the late 1940s through the early 1960s, nearly one million Oriental Jews scattered to the four winds . . . for Israel and America, as well as fanning out to Italy, England, Spain, France, even Australia and distant corners of Latin America.

Called “the Captain,” Leon was a confirmed bachelor, a boulevardier, a man about town who was rumored to have had as one of his mistresses the famous Arab singer Om Kalsoum, who was also a Muslim. Yet Leon was a devout Orthodox Jew, a living paradox, a man whose business in exporting and importing was never entirely clear, but who made a good living, whose fine features and great height made him well known as he cut a stunning figure in Cairo, especially at night, prowling the clubs and bars and good hotels in his white sharkskin suit. Then, as if they were in a movie, he spied Edith Matalon, at least two decades younger, in a cafe in 1943 and became smitten with this timid, intellectual girl who worked as a teacher and librarian in L’Ecole Cattaui, the private Jewish school in the Sakakini neighborhood where Edith lived with her mother Alexandra and her brother Felix, a girl who valued, above all, her friendship with Alice Cattaui, the wife of the Jewish Pasha Cattaui, and whose prized possession was the key to the Pasha Cattaui’s lavish library.

But Edith also had what Leon treasured above all: beauty, and also youth. “I find you very beautiful. Would it be possible for us to meet?” he wrote on a slip of paper which he asked the maitre d’ to deliver to the table where Edith and her mother Alexandra were delicately sipping their Turkish coffee.

And so it began.

After their marriage a few months later they lived with Leon’s mother Zarifa, who was born in Aleppo. Her Syrian Jewish background had given her expectations for her daughter-in-law that Edith could never hope to meet. Moreover, convention made it impossible for Edith to continue to work, and within a month of the marriage ceremony Leon was once more out and about, alone, and even left the marriage bed for his old room at the front of the house on Malaka Nazli Street — a different world from Sakakini — to which he could freely return in the early hours of dawn, which was when he usually came home.

It was a disaster, and got only worse once the children started coming. Two people who made a beautiful couple but who were absolutely incompatible. Who had such different interests and ways of looking at the world that they didn’t seem able to negotiate any kind of amicable truce. Despite her intelligence and elegance Edith suffered more, deteriorating both mentally and physically in ways that frightened her children. And Leon was often remote and tyrannical. From a child’s point of view it made no sense, but there have been many marriages exactly like Leon and Edith’s, which is why the epigraph to The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit from Delmore Schwartz’s great story “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” is so apt. A child is watching a movie in which is there is a romantic encounter between two people like the one described above. He is overcome by the reality of his life:

It was then that I stood up in the theater and shouted: “Don’t do it. It’s not too late to change your minds, both of you. Nothing good will come of it, only remorse, hatred, scandal, and two children whose characters are monstrous.

An indelible quotation which haunts everyone who writes about families. Yet, as Tolstoy reminded us, it is the dysfunctional families who are most interesting. But only if they are written about with generosity and intimacy, both of which give authenticity to the work. That is what Lagnado does so superbly. She lets her memory lead her to those moments and events that matter, she digs deeply into her feelings, she eschews chronology and has written these two books with an ease that comes only to someone who knows her material thoroughly and who can write with authority about events taken out of order and at the same time keep it all straight so that the reader is never at sea. Here is an example of that ease — she is describing a event that happened before she was born, yet she is totally present:

Shortly after giving birth to a baby girl we named Alexandra, Mom was diagnosed with typhoid fever. The disease that had killed Indii Cattaui nearly half a century before was still the scourge of Egypt. My mom’s fever raged and everyone around her gave up hope, especially when the baby caught the disease.

But then a young doctor from . . . the local Jewish hospital arrived to pull off a miracle. . . . he was especially adept at treating cases of typhoid and now, unlike the time of the pasha’s daughter, there was a powerful weapon at a doctor’s disposal—a drug named chloromycetin that was remarkably effective.

Mom survived; my baby sister did not.

Moreover, once divorce was ruled by the grandmothers and aunts as totally out of the question in the early 1950s, Edith and Leon seemed to settle down; after Loulou’s birth they were able to pull it together, especially when the stakes were high — when Loulou got cat scratch fever at six years old, and then later when she was treated for Hodgkin’s disease when she was 17. When Leon shattered his hip in an accident as they were debating where to go after leaving Cairo, and even afterwards when they came to Brooklyn and had to live a very sparse life until Edith got her job at the Brooklyn Public Library on Grand Army Plaza. Or when Suzette acted up.

There seemed to be very little joy, yet they were a family. Lucette faces the pain in her life without self-pity or special pleading. The section in which she describes how she made the decision not to save her eggs — which necessitated an operation at that time — and her regret afterwards is so moving because of her refusal to sentimentalize any of it. This is the way it was, she is saying, and my first priority was to survive. Almost as if she knew it would be her task to care for Leon and Edith until their deaths.

She is also generous to the reader and gives us back stories of the aunts, a cousin, and even an errant uncle, Leon’s brother, who becomes a Catholic priest, to the shame of Zarifa, forever. There is an indelible portrait of Edith’s mother Alexandra, a single mother who never knew what to do when her husband Isaac left after committing the most despicable act one can imagine and whose wealthy background left her utterly unprepared for her single life, which ended in disappointment and despair in Israel. Which is why Edith became old beyond her years and so superstitious and unsure of her own worth.

It is all there: the smells and sounds, the customs and mores of the Middle East — to give ballast to this story whether its characters are in Cairo or Brooklyn, where the family lands in 1963. Once there, though, their world shrinks, circumscribed by the synagogues in the neighborhood and the schools Loulou and her brothers attend. By then Suzette, the wayward child who will never return and never fulfill her responsibilities as the oldest, is gone; Isaac and Cesar are teenagers; only Loulou can help rebuild the hearth, as Edith keeps reminding her in French. They are poor, Leon is reduced to selling ties on the street, a landlord screams at them because they have no decent furniture, Leon searches for the ideal synagogue, and Edith is lonely and melancholy until she finally finds a job. Only at synagogue can Loulou indulge herself in the usual adolescent fantasies about sitting in the men’s section and flouting the rules of Jewish orthodoxy, about asserting herself as a young woman, about falling in love; here is a safe place where she can be just an ordinary teenage girl.

So, in a way, this is also a coming-of-age story, a sometimes painful account of how to find friends and approval from selected adults, and then, out of the blue, to know what it means to be seriously sick in a New York that is not particularly hospitable to immigrants, to live with a mother who will never face what is happening directly and deal with it, to see a powerful, almost legendary father fade. Yet Loulou prevails; she bonds with her doctor at Memorial and listens carefully to his counsel; after a disastrous freshman year at Vassar she goes to Columbia and gains enough confidence to return to Vassar and graduate, and then embarks on her career as a journalist. Although she never gushes, it is clear that she and Feiden (what she calls her husband) have a rare lucky marriage, and that he not only helped her care for her sick parents but also gave her the love and support she needed to do her work and write these books. Who understood the strong bonds between Loulou and those complicated, often remiss parents whom she loved so dearly and who, she knew in her heart, did the very best they could.

Her death was surely a blow to everyone who knew and loved her. I felt it when I closed the last page of The Arrogant Years. To have such a remarkably courageous voice silenced forever at such a young age is, simply, not fair. But she left something permanent in the world: essential books to cherish and reread and give to our kids and grandkids, whether we are Jewish or not. For a serious writer, it doesn’t get much better than that.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

This sensitive and beautifully written review by Roberta Silman s wonderful. Although I felt saddened by her comments about “the

Five Towns.” I too spent many years there and not unhappily and certainly did not feel suffocated. Even so, her description of the

authors two books were exciting. I immediately ordered both booksfrom Amazon.Thanks Roberta. I have enjoyed your writing, especially your last novel.

Best to you, Joanne Kass

This is a wonderful, fascinating review. I am all set to delve deeply into The Arrogant Years.

Thank you, Roberta!