Book Review: The Lives They Wrote

By Marcia B. Siegel

Two autobiographies by women who had some experience in legitimate theater, but they each gave their strongest allegiance to dance, specifically one choreographer.

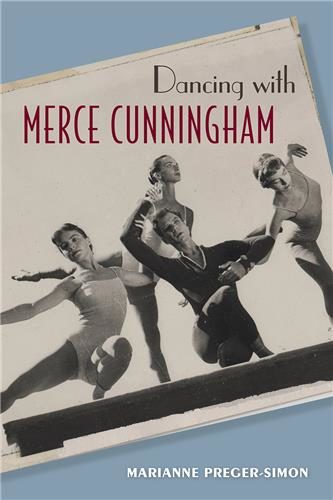

Dancing With Merce Cunningham by Marianne Preger-Simon. University Press of Florida, 203 pages, $19.95.

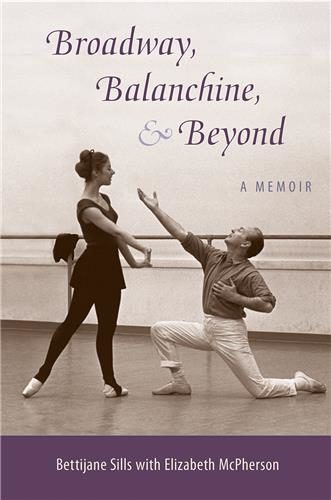

Broadway, Balanchine & Beyond by Bettijane Sills with Elizabeth McPherson. University Press of Florida, 178 pages, $19.95

By Marcia B. Siegel

Any piece of writing is selective, even autobiography. Especially autobiography. Two recent self-portrayals depict very different dancers, surrounded by vastly different worlds. Both women had some experience in legitimate theater, but they each gave their strongest allegiance to dance, specifically one choreographer. Preger accompanied Merce Cunningham at the outset of his dance company and joined his early explorations into choreography. Bettijane Sills started lessons at George Balanchine’s school as a child. She entered his company, New York City Ballet, at the crucial moment when it was making the move from the stodgy old City Center theater to Lincoln Center, newly built and soon to be a national culture mecca.

Any piece of writing is selective, even autobiography. Especially autobiography. Two recent self-portrayals depict very different dancers, surrounded by vastly different worlds. Both women had some experience in legitimate theater, but they each gave their strongest allegiance to dance, specifically one choreographer. Preger accompanied Merce Cunningham at the outset of his dance company and joined his early explorations into choreography. Bettijane Sills started lessons at George Balanchine’s school as a child. She entered his company, New York City Ballet, at the crucial moment when it was making the move from the stodgy old City Center theater to Lincoln Center, newly built and soon to be a national culture mecca.

Marianne Preger was one of the earliest Merce Cunningham dancers. While studying acting in Paris on a year off from college, she saw a performance he gave with ballet dancers Tanaquil LeClercq and Betty Nichols. Preger arranged a space for him to teach there, and she became his first student when he started giving classes back in New York. She joined him and his partner John Cage in 1950 at Black Mountain College, where he formed his first company. By the time she left in 1958, the company had survived its infancy and was gaining a foothold as a major—if still esoteric—factor in the modern dance world. Preger remained a close friend until the company ended shortly after Cunningham’s death in 2009.

For her book Preger-Simon smoothly knits together photographs, fragments from letters, diaries, press notices, and retrospection. She evokes the dirt-poor days in Greenwich Village when the dancers had to scrape together the rent from part-time jobs. They made their own costumes and drove to out-of-town engagements in a minibus that could hold the entire company. She danced in the repertory of those vintage years — Dime-a-Dance, Banjo, Minutiae, Suite for Five, Septet — and provides inside information on these and other disappeared works of the ’50s. She was there as Cunningham was developing his teaching and choreographic methods. A keen observer and letter-writer, she can recount conversations she had with him and Cage about their developing aesthetics.

The book includes funny and poignant anecdotes about her fellow dancers, their celebrations, injuries, escapades. She remembers sitting behind Robert Rauschenberg’s set-piece while waiting for her entrance in Minutiae (1954), and reading the comic strips on the back of the collage decor. (One panel of that set was included in the Institute of Contemporary Art’s show on Black Mountain College a couple of years ago.) Preger-Simon gives a lively sense of the people she worked with, especially her close friend, company dancer Carolyn Brown, and the elusive Cunningham. She reproduces the choreographer’s letters and cards to her, many with his charming sketches in between the lines.

Despite dance critic Alastair Macaulay’s expansive Afterword, this is not a book for learning everything about the history of Merce Cunningham. For that, the best sources are David Vaughan’s Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years and Carolyn Brown’s autobiography Chance and Circumstance. What Dancing with Merce Cunningham gives us is the generous and loving presence of its author, who understood the value of the work she was doing and the people who did it with her.

Bettijane Sills was — and is — devoted to George Balanchine. Propelled by her ambitious stage mother, she started a busy career in shows and television while still a child. She began classes at George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet at the age of 8. When she entered New York’s High School for Performing Arts, she pretty much gave up professional acting to major in dance. The faculty at HSPA included dance teachers of many styles, but Sills kept up her after-school studies at SAB, gaining the notice of the New York City Ballet teachers there. She finally joined NYCB after her graduation in 1960. Over the next years until she left the company in 1972, Sills rose from the corps de ballet to a favored cadre in the ballets of Balanchine and the few other choreographers who supplied the repertory in the ’60s.

The company didn’t divide the dancers into severe rankings then, but Sills and half a dozen other women appeared often, to create a layer of complexity unique to Balanchine’s choreography—a line of counterpoint between the solo dancers and the larger corps. They weren’t officially soloists but Balanchine gave them intricate steps to do and you could notice them as individuals if you went to City Ballet often enough. I admired Sills in those days.

Like many in the cloistered atmosphere of the company, Sills worked hard and struggled to keep up with Balanchine’s demanding standards. As a post-adolescent, she couldn’t keep her weight under control. This meant that when she put on a few pounds, she’d be taken out of ballets. Sills’s book is candid about her weight problems in NYCB, but it’s not a tell-all like the confessionals of Gelsey Kirkland or Toni Bentley. By 1972 she had married, and she was eased out of the company, advised to find something else to do. What she found, eventually, was teaching.

She began slowly, occasionally substituting for former NYCB principal dancer Diana Adams in the Dance Department, now the Conservatory, at the State University of New York at Purchase. After some time off to give birth to a son, she began teaching on her own, her new family having moved to the Westchester suburbs. Eventually she returned to Purchase as a full time teacher, earning a bachelors degree from Empire State College. She’s still at Purchase, a tenured professor, and in additional to her teaching, she stages student concerts, choreographs her own ballets, and stages Balanchine’s work for them.

Sills doesn’t explain how she learned to be a ballet teacher and coach. But copying and correcting are an essential part of a dancer’s life in a big ballet company; the smart ones can learn a lot, even if they don’t plan to make it their career. This book is the story of a girl growing up, who finds her independence without losing her ideal.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. She has contributed two selections to Dance in America, the latest edition in the Library of America’s “Reader’s Anthology” series.