Book Review: Dancer Ray Bolger — America’s Animated Cubist

By Janine Parker

Via Ray Bolger’s trajectory we traverse the boards of Broadway and the silver screen of Hollywood — as well as the smaller, but equally thrilling, milieux of nightclubs and television studios.

Ray Bolger: More Than a Scarecrow by Holly Van Leuven, Oxford University Press, 256 pages, $29.95.

I imagine they exist, but I’ve yet to meet anyone over the age of ten who hasn’t seen the 1939 classic film The Wizard of Oz, the fantastical technicolor spectacle that still thrills (and scares, and resonates with) viewers of all ages, even in this era of video games and films rich with sophisticated animation and computer-generated imagery. Yet I don’t know how many people could name Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Bert Lahr, the actors who played the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Lion, respectively. Well, do the younger generations know the name Judy Garland, who played Dorothy, either? Still, though many of us of a certain age do have those beloved Oz actors’ names embedded in our memories, I suspect that most of our knowledge — perhaps aside from Garland — of that golden team ends with that famous yellow brick road.

In the introduction of her new biography of Ray Bolger, author Holly Van Leuven acknowledges that reality but also cheerfully informs us that Bolger had a rich, successful career, a journey in which the yellow brick road was only one section on a well-traveled map.

Van Leuven came to Bolger through her interest in American musicals from the 1930s and 1940s, two decades shadowed by first the Depression and then WWII, a time when US citizens were starved for the escape that entertainment could offer. That particular era also saw the yo-yoing of public taste, as various forms of entertainment — the live action of vaudeville, revues, as well as, eventually, musicals, and the burgeoning field of motion pictures — fought to curry popularity with theater-goers. A very 21st century research tool — scrolling through YouTube, natch — led her to some obscure clips of Bolger, who died in 1987. Her curiosity piqued, Van Leuven followed a trail of bread crumbs that led her to some of Bolger’s extant colleagues and family, eventually getting access to Bolger’s previously unpublished papers.

Born in 1904, in Dorchester, Massachusetts, to Irish Catholic parents who ultimately separated (but didn’t divorce; remember the times and, more, the looming Church), Bolger grew up in meager conditions. His mother died when Bolger was a teenager and although his itinerant father moved back in, his wavering health meant that young Ray was called on to become the primary breadwinner. In his senior year of high school, Ray attended classes for half the day and then went to his job at the First National Bank in Boston’s financial district. If Bolger had no early dreams of becoming a performer, he was nonetheless drawn to the world of live entertainment that he saw, literally, in the streets, during his daily travels.

“Just beyond the bank in Winter Street,” Van Leuven writes, “Scollay Square overflowed with actors and hopefuls.” In addition to “Austin and Stone’s Dime Museum, a freak collection curated by P.T. Barnum,” the nearby Old Howard offered a new burlesque show each week. “Between the [two] acts of burlesque were three acts of vaudeville.” You could get all-day admission for ten cents, but for free you could watch the equally colorful street shenanigans, where local boys and men showed off their dance chops, much in the way, from the sound of it, that b-boys and b-girls would do decades later.

“Boys of Boston interested in dance swapped steps with each other,” Van Leuven writes. Bolger absorbed a fascinating potpourri of movement styles inflected with, among other flavors, Irish and African-American dance traditions. Though Bolger ultimately honed a physicality that seemed unique, it was partially shaped by his mimicry of others. Like the myriad sketches and acts in a vaudeville show, Bolger’s “style” was an amalgamation of the many approaches he saw and emulated: the rubbery-legged acrobatics of “eccentric” dancing; the hybrid form of tap dancing he adopted; and the very scant formal training he picked up, some of it just by observing classes taught by old masters whose studios he cleaned in exchange for lessons (and sometimes a cot to sleep on). Still, though one could see traces of this or that in Bolger’s dancing, in the end his style was best described as, well, that of Ray Bolger. In addition to glimpses of his beloved, borrowed-from-ballet pas de chats, this clip from 1941 shows his “split” routine, which he developed, as Van Leuven tells us, by way of specific training exercises for his hamstrings.

A writer once playfully, and perfectly, described Bolger as an “animated cubist.” And how did Bolger define himself? He waffled; sometimes he fretted about why his comedy wasn’t seen as his main gift and at other times he complained that he wasn’t being fully appreciated as a dancer. “Physical comedy” seems to be what he mostly settled on in terms of description, and that indeed seems apt. As Van Leuven points out, while he could get away with a certain amount of singing and broad acting, those weren’t dependable strengths in his wheelhouse.

In any event, his own innate talents, and an apparent ability to absorb information quickly, meant that after dancing up and down the stairs at the bank he was soon kicking, and cutting up, for pay. Street challenges led to amateur nights (with the allure of cash prizes) and, for Bolger, breaking into the vaudeville circuit. “In Bolger’s time and place, entertaining was not a lofty, artistic ambition,” Van Leuven writes. “It was a good way to survive, and in his realm of experience and opportunities, the only way to thrive.” Although Van Leuven lucidly traces the efforts, and the fits and starts along the way of Bolger’s ever-expanding career path, the speed with which he progresses and makes professional inroads is dizzying. And exhausting: Bolger’s life as a vaudevillian, and even later, as a film star, (and briefly, a television personality) was as itinerant as that of a traveling salesman — like his father.

Despite his outsized Scarecrow celebrity bump, Bolger hasn’t remained a household name. But the arc, breadth, and specificities of his career make him a prime specimen through which to consider the arc, breadth, and realities of the world of entertainment in the US. While biographies of bigger names can be absorbing reads, the dazzling details of a star can overshadow the everyday slog, as well as the evolution, of popular entertainment. Deftly, Van Leuven weaves the micro of one performer’s career into the macro of the many-forked US show business. Via Bolger’s trajectory we traverse the boards of Broadway and the silver screen of Hollywood — as well as the smaller, but equally thrilling, milieux of nightclubs and television studios.

As the various wings of the entertainment business fought for dominance, Bolger zigzagged among his various talents while he zigzagged around the country, following the jobs. While out on the West Coast, he met the woman who would become his wife, Gwendolyn Rickard. Though a talented and versatile performer herself, Gwen decided, soon into their marriage, that instead of following the vaudevillian tradition in which performing wives joined their husbands’ acts, “she was willing to give up her hopes of becoming a star in her own right…to support Bolger.” While readers now may sigh at that arrangement (another woman’s career dreams subjugated to a man’s), Van Leuven suggests that Gwen was confident and independent. She made the choice of her own volition; she had enjoyed “the life of a smart, vivacious young woman in a period when ideas about femininity were rapidly changing…[she] considered herself the intellectual equal of men.” The couple seems to have enjoyed a loving and respectful relationship, and Gwen indeed dove fully into the work of not only supporting, but propelling, Bolger’s career, for all intents and purposes his manager. “The importance of Gwen’s entering Ray’s life cannot be overstated,” Van Leuven asserts. “Their union was the prime reason that Bolger became a star. He had talent, dedication, and an astonishing work ethic…Gwen…provided him with strategy and savvy.”

From dancing in the stairwell at his job in the financial district, we follow Bolger along the unceasingly on-the-road world of vaudeville, from the rise of the “book” musical and the burgeoning of films to live, “on-air” radio and, eventually, television shows. Bolger worked constantly and — without the help of the internet! — became an acclaimed star of his time. Yes, Oz brought him widespread recognition, but he’d already garnered a multitude of fans — audiences, yes, but there were plenty of admiring newspaper critics too — from his live stage work. Indeed, although he, with the help of Gwen, and his lifelong agent Abe Lastfogel (“the most honest agent in the world”), did a fair amount of chasing gold via the silver screen, Hollywood was often a frustratingly elusive world for Bolger to gain a foothold in. Movies ultimately claimed a relatively smaller portion of his overall resumé. Meanwhile, by the time television gained prominence, Bolger had been performing for decades. At first, his big name helped him to gain entry into this newer venue; but after a while it was apparent that Bolger’s relatively old-school ideas clashed with his younger colleagues’ methods — an illustration of the ‘generation gap’ of the 1960s and ‘70s. To some of his younger colleagues, Bolger was an out-of-touch crank. (And with a bossy wife to boot, some thought.)

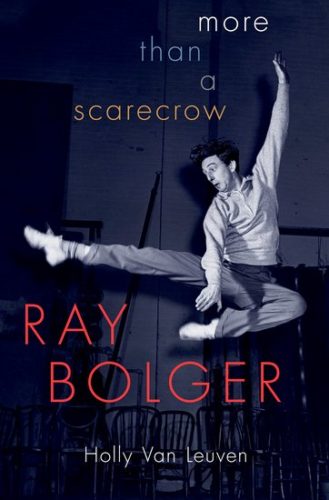

Ray Bolger in action.

As far as “celebrity” biographies go, this book is low on the gossipy scale. In the same way that the physical book itself is handsome, yet sober (the black-and-white only photographs are scattered throughout the book rather than bunched into glossy galleries that, of course, would have been delicious), so too are the anecdotes PG-, if not G-, rated. No bodices are ripped, no one stumbles drunkenly onto the stage. People drink, people smoke — and sometimes to excess, but mostly that is put down to stress and overwork. Though I applaud the civility, Van Leuven could have drawn aside the curtain occasionally: at times the proceedings feel unnecessarily sanitized. Writing about the teenaged Garland being slapped on the Wizard set, Van Leuven softens the blow: “While this was a common form of reprimand for a child at that time, Bolger must have felt uncomfortable as he watched Garland, whom he cherished, get a scolding.”

That “must have” casts Van Leuven in the role of apologist; that “common form of reprimand” and “scolding,” meanwhile, sound tone-deaf in 2019. Instead of writing, as if hopefully, “Bolger must have felt uncomfortable,” why not pose it as a query: “One wonders if Bolger felt uncomfortable…?” (Later in the book, Van Leuven does reference the tough conditions and rough ways in which Garland was sometimes treated as contributing to the performer’s tragic downward slide.) I’d also like to hear a bit of what Bolger thought about in terms of the racial and ethnic inequalities his non-white counterparts were experiencing during his decades in the entertainment field. And, did he have opinions about his gay colleagues? These may not have been topics for polite conversation then, but people have always had opinions of such things, whether they spoke of them publicly or privately. (Perhaps these matters weren’t anywhere to be found in Bolger’s papers; I certainly hope there are no ugly skeletons of the prejudiced kind in our beloved Scarecrow’s closet, but the silence on Van Leuven’s part makes me wonder.)

These are questions, however, not necessarily shadows: undoubtedly, Bolger is an American entertainment icon and, given his brave tours with the USO, also arguably an American hero. His politics were conservative, along the Republican/Libertarian line. This may be a small disappointment for some Bolger fans, particularly when reading about his apparent knee-jerk reaction during the tense paranoia of the HUAC era. But, like a good journalist, Van Leuven maintains a proper neutrality here, as in most of her book. In her introduction, she assures us that Bolger was “more than a Scarecrow.” If that phrase (and the book’s subtitle) also sounds a bit like the title of a graduate student’s thesis, well, Van Leuven skillfully defends her claim. She writes with clear prose that is straight-forward without being dry, juggling and laying out the variety of facts and events of Bolger’s life and career with an uncluttered ease. And, true to her word, while Bolger’s Scarecrow gig gets its due as a prominent role in his resumé, it isn’t allowed to upstage Bolger’s many other career highlights, nor does the role dominate the book.

Still: Bolger was a Scarecrow for the ages. (And perhaps for ages to come.)

Janine Parker can be reached at parkerzab@hotmail.com.