Theater Review: HD Hamlet — Determined Relevance

Royal National Theatre Director Nicholas Hytner is determined to make the drama as relevant to our own times as to the Bard’s. The setting is a somewhat flimsy, gray-walled salon. Theatrical apparatuses are visible: a klieg light here, a fresnel there.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare. Staged by the Royal National Theatre, London, England. Taped by HD multi-camera and shown at the Coolidge Corner Theatre, Brookline, MA. Next screening of Hamlet, December 20 at the Coolidge Corner Theatre.

By Joann Green Breuer

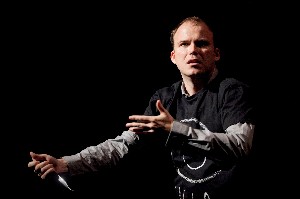

The second most popular Shakespeare character of his times, after Falstaff, returns to the London stage in the personage of Rory Kinnear, yet another “definitive interpretation,” with the usual caveat, “for his time.” From mid-twentieth-century Laurence Olivier’s gold-trimmed, velvet doublet to today’s smiley face t-shirt, production sensibilities have taken a long interpretive leap from romantic, royal composition to scruffy, street chic. What is lost is Hamlet’s conventional nobility. What is gained is his consistent intelligence. What is never in doubt, despite deceptive falsetto phrasings, is his sane connivance, his grasp of every word he says—and doesn’t say. There is method in his pauses, which passes madness.

Director Nicholas Hytner is determined to make the drama as relevant to our own times as to the Bard’s. The setting is a somewhat flimsy, gray-walled salon. Theatrical apparatuses are visible: a klieg here, a fresnel there. There will be a play within the play. If truth is to be uncurtained through that scene, why not let the whole play itself be a teller of truth? It is a nice intellectual concept of Hytner, mostly, with significant exceptions, irrelevant. One wants to lean back and suspend forward in make-believe belief. Once, however, Hamlet focuses a stage light on himself and, as if perceiving himself anew, says with amazed credulity, “o, what a rogue and peasant slave am I.” A chilling moment, almost justifying the conceit.

The playing space is unadorned save for a portrait of old King Hamlet, later replaced by a modestly smaller one of new King Claudius. Murder and immediate marriage to widow Gertrude, mother of Hamlet, are catalysts for the subsequent tragedy. It is a sign of the times, ours and Shakespeare’s, and of Claudius’s paranoia that behind each movable wall, door, and plastic widowpane lurks a gray-suited functionary, ear piece and pistol moored appropriately. Their presence is noted and accepted by Hamlet (and audience), ominous but unobtrusive, seemingly innocuous until Ophelia’s final exit when they do far more than merely accompany her. What? She did not commit suicide? A (to me) unique reading which, oddly, bears no additional consequence in this production. Hamlet, who claims he loved her, and Laertes, her brother who certainly did, do not color their grief with blame. The message is that there are some whom the government kills and no one notices—not even the strikingly intelligent, hesitant Hamlet. There lies the contemporary rub.

Hytner permits little extraneous movement by anyone. Hamlet remains still as he opens each soliloquy. He delivers direct addresses. His focus, and the production’s, is on a respectful and revelatory approach to the text. At a sudden phrase, Hamlet leaps to brave a newly perceived obstacle, within himself or his circumstance. He can move like a rat, and he is content, or condemned, to husband his physical energy.

On the HD Experience

Peter Gelb, artistic director of the Metropolitan Opera, took his productions into movie houses around the world with HD presentations. Tickets which ordinarily cost hundreds of dollars for close seats, less where binoculars are needed, suddenly were accessible, financially and geographically, to thousands of patrons of limited means. Each viewer has an unobstructed seat, back stage views, and the thrill of hearing miraculous music and musicians. Wow. The Royal National Theatre noticed.

Does one gain as much watching spoken stage on screen as one does listening to song? It’s not the same as being there. The camera focuses for us, possibly making us lazy or miss our choice of perspective. However, HD is a real gift, if not a substitute. Kudos to the Coolidge Corner Theatre (CCT) for bringing Royal National Theatre (RNT) performances to the area—a kick, however, to the CCT in the kiester for making audience wait in long lines outside no matter the weather. Is that really necessary? I doubt it. Seat audience as soon as the theater is cleaned from the previous showing. Theaters showing operas do. Witnessing preparatory sound and shot tests on the screen only adds to the experience. Meanwhile, for January’s RNT Fela at the Coolidge, I recommend a sturdy parka. With a hood.

— JGB

When Hytner attempts metaphor in monologue, it is often intrusive and clumsy—why does Hamlet smoke those cigarettes? Why fling that quilt over his head in fake, feigned madness? Kinnear’s Hamlet is best when defenseless, save by his language, which provides both impetus and eloquent impediment. Thinking often seems to make it so. His duel with Laertes, choreographed within a clear story line by Kate Walters, is stunning proof that Kinnear can move with delicate alacrity should necessity demand. His body, like his mind, is ever in control.

Alcohol is nourishment to Claudius and Gertrude. They are rarely without shot glass in hand, tipped to lips, although only Gertrude exhibits tipsiness. Is drinking the royal habit and affliction? Was King Hamlet on the garden ground dozing off an afternoon’s swill when Claudius poisonously interrupted his little life with permanent sleep? A reasonable implication in this production, although Hamlet, who after much self-debate is convinced that the Ghost is not of the Devil, would no doubt have none of that assumption.

Hamlet is the belligerent defender of his father’s virtues, which makes him sound at times like an over-the-hill adolescent, an impression strengthened by Kinnear’s baby face and balding pate. The King did not merit murder, but, as Gertrude says, sometimes this son doth protest too much, methinks. A line, by the way, which Gertrude delivers remarkably ingenuously, as though neither she nor I had not heard it before. Claire Higgins, as Queen, aging not altogether gracefully, blends desire with an undercurrent of doom. She senses that this peace may pass. Her toast, her final one, to her son’s fencing coup feels less like an ironic celebration than the inevitability of addiction. Higgins finds dimension and duality in Gertrude’s public and private worlds. When she speaks of the willow bending over drowned Ophelia, sorrow, tenderness, and a tinge of bitterness color her mind’s eye.

David Calder, as Polonius, embeds sincerity in his verbosity. His pause, seconds before he comes up with “cannot then be false to any man” suggests how he can surprise himself with new birthed wisdom. The camera did not allow us to see if Laertes and Ophelia, half-listening with bemused impatience, were likewise impressed. I missed seeing their reaction.

Others in the cast proffer mixed achievements. James Laurenson, doubling as Ghost of King Hamlet and the Player King, was of two grades. His Ghost was conversational, casual—what is to be feared? His clothing, rumpled mufti, belied the armor described. No beaver, nor mention of it, up or down. In shabby ulster, unshaven visage, he seemed more the wandering, impotent alcoholic implied earlier than the fearless warrior of his son’s imaginings. In a lovely touch of casting, Calder was also the Player King; relaxed in rhetoric, in command of verse and sense, he gave quiet power and honor to lines often lost amid the play’s furies. His artistic semblance was more a king than any actual earthly king of Elsinore.

Hamlet addresses his advice to the players to the actress playing the Queen. There is obviously no need to offer it to the Player King, a master of the theater. This speech is more impassioned than any other in the play; Hamlet implores with desperation that the players commit themselves to the text. Hamlet has crafted the scene, of course, but his trust in theater, not in his own authorship, is what really pours from his being. Herein lies, herein flies, the core of Hytner’s concept. Theatrical trappings are not what passeth show but the visible soul of woe.

Patrick Malahide as Claudius slips more and more into villainous mien from act to act. His smile, detested and graffiti-ed by Hamlet, was subtle but undeniable, less a cover for guilt than lip-licking satisfaction. Alex Lanipekun as Laertes and Giles Tererra as Horatio were undistinguished, adequate but enhancing little. Ruth Negga as Ophelia, even dressed down to bra and skirt, did not engage attention. Her mad scene, pushing a shopping cart, a thing of rags and swatches, had neither melody nor meaning. Her earlier betrayal of Hamlet via a microphone her father Polonius inserts into a Bible which she carries, rather too obviously, into Hamlet’s chamber is awkward and not just because Ophelia would be discomfited by the task. Ferdinand Kingsley and Praswanna Puwanarajah as Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern made sharp Tweedledum/Tweedledees, moving and clad in gleaming tandem, hoping that their onerous task would prove more benign than they suspected.

We think we know Hamlet—man, son, fulcrum of his universe. Yet we want to know him more. We forgive him his choices because for him there are no good choices, and, in delaying making them, he is brilliant and pained. We look at each production, each interpretation, to see what can be found or brought new, as well as to find comfort in the familiar. We have few kings, but we know of dictators, and we are wary of democracies verging towards tyranny. We, too, are bugged. And we, too, are blessed that our language is so close to Shakespeare’s. With such comprehension comes responsibility. It may not be divinity that shapes our ends. Readiness is our obligation. Hamlet, by now a mythic portrait of this secular trinity, step-father, son, and (to Hamlet) holy ghost, awaits our next visit and a next inspiration.

Joann Green Breuer is artistic associate of the Vineyard Playhouse.

Tagged: Coolidge Corner Theatre, Hamlet, HD, Nicholas Hytner, NT Live, Royal National Theatre, Theater

I generally agree with Joann’s thoughts on “Hamlet” — I am not sure what all the London critics were excited about.

The authoritarian political context becomes laughable — do we really need to have Hamlet threatened with truth serum so he will reveal where Polonius’s body is? And secret service agents are supposed to stay in the background — here they stand near the action, as if they were stars.

And the final duel reminds me of Marx Brothers’ Freedonia — Gertrude is poisoned and all the secret service agents run out the the room (leaving the King completely unprotected) to round up the usual suspects. And if the agents can kill Ophelia and make it look like suicide why not Hamlet? He has gone mad after all…

On a more serious note, the notion of an authoritarian state undercuts the poetic and psychological power of the tragedy — what is the fuss if Hamlet loved his father the totalitarian dictator? Surely a police state hasn’t been set up in under two months. There is no chance of justice in this Elsinore — Hamlet doesn’t talk about creating a fairer government, just avenging his father’s death. So the father’s death is not, as Gertrude implies, all that “particular.”

Kinnear is an intelligent and well-spoken Hamlet, but there’s no sense of nobility or precious opportunity destroyed with his demise.